African Americans in the U.S. Coast Guard

The primary federal agency with maritime authority for the United States, the U.S. Coast Guard is the smallest of the United States’ five armed services. A full-time military organization with a true peacetime mission, the service numbers 90,000 strong with all components added in, including Coast Guard Reserve and Coast Guard Auxiliary.

Spanning more than 230 years, the history of the Coast Guard is as diverse as it is long. Unlike some federal agencies, the Coast Guard did not begin at any one time or with any single purpose. Today’s Coast Guard is a collection of other federal organizations no longer in existence. The Revenue Cutter Service, forerunner of the Coast Guard, was established in 1790 under the Department of the Treasury. Congress authorized the building of the first fleet of ten cutters (a vessel 65 feet in length or more that can accommodate a crew for extended deployment).

The Service was renamed the Coast Guard in 1915 when it merged with the Life-Saving Service, which began in 1878. Established in 1789, the Lighthouse Service joined the Coast Guard in 1939. In 1946, the Bureau of Navigation and Steamboat Inspection was permanently transferred to the Coast Guard. After 177 years in the Treasury Department, the Coast Guard transferred to the newly formed Department of Transportation on April 1, 1967.

The Coast Guard is a complex organization of people, ships, aircraft, and shore stations. The Service is decentralized administratively and operationally. Coast Guard personnel respond to tasks in several mission and program areas. This multi-mission approach enables a relatively small organization to respond to public needs in a wide variety of maritime activities and to shift focus at short notice.

The Coast Guard now carries out 11 missions. These missions mandate the Coast Guard remain constantly ready to defend the United States while also ensuring national security and protecting national interests. The service is also to minimize loss of life and property, personal injury and property damage at sea in U.S. waters; enforce U.S. laws and international agreements of the United States; ensure the safety and security of maritime transportation, ports, waterways and shore facilities. The Coast Guard also promotes maritime transportation and other waterborne activity in support of national economic, scientific, defense and social needs. It protects the marine environment and its wildlife and ensures an effective U.S. presence in polar regions It also protects the interests of the United States in relationships with other maritime nations worldwide; assists other agencies in performance of their duties and cooperates in joint maritime ventures while providing an effective maritime communications system. Finally, it operates under the U.S. Navy, when directed by the President.

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN THE REVENUE CUTTER SERVICE

The Coast Guard traces its primary root to the Revenue Cutter Service, which was a "military" organization from its inception and which element has modeled the character of the Coast Guard probably more than any other.

The first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, proposed the Federal government accept public responsibility for safety at sea. On August 7, 1789, President George Washington approved the enabling Ninth Act of Congress. To counter the smuggling and other illegal activities rampant at this time, Hamilton proposed a seagoing military force to support national economic policy. Mere legal-paper status was not enough to combat criminal activity: on August 4, 1790, what was eventually named the Revenue Cutter Service, came into existence.

The enabling legislation, the Organic Act, provided for establishment and support of ten cutters (vessels 65 feet in length or more, that could accommodate a crew for extended deployment) to enforce the customs laws. Hamilton also requested a professional corps of commissioned officers.

The first commissioned officer was Hopley Yeaton, commanding officer of the Revenue cutter Scammel. Yeaton, a veteran of the Continental Navy, owned a slave named Senegal who served Yeaton on many cruises. Alexander Hamilton’s request for "ten boats" for the protection of revenue specified each be armed with swivels, small cannons on a revolving base that could be turned and fired in every direction.

Historical records of the Service reveal that the practice of officers using slaves as stewards, cooks and seamen on board Revenue cutters appears to have been a common one. A Service regulation dated November 1, 1843 officially banned this practice by prohibiting any slave "from ever being entered for the Service, or to form a complement of any vessel of the Revenue Marine of the United States ."

Before 1843, Revenue cutter captains’ use of slaves and other African Americans had been restricted. Captain W.W. Polk, USRCS, commanding the Revenue cutter Florida , wrote Treasury Secretary Samuel D. Ingham on June 22, 1831:

In the general instructions for the government of the Revenue Cutter service of December last, by one paragraph is prohibited the employment of persons of color, unless by the special permission of the Secretary of the Treasury

I beg leave here to observe that I have never owned a slave in the Cutter Service. I have however a colored boy, a native of N. York and of course free, he was given to me by Capt. M.C. Perry of the Navy. He is now bound to me under Laws of Delaware until age 21.

If it would not be incompatible with the rules laid down by the Hon. Secretary I have respectfully to suggest that I may be permitted to employ the boy as a servant on board. He is an expert sailor for his age and competent to the duty of a boy of the first class. I would further respectfully ask if the Commanders of Cutters are permitted to employ apprentices, and if so how many.

Secretary Ingham replied six days later that there "will be no objections to your retaining your servant Boy and shipping colored persons as cooks and stewards." The following month, Acting Secretary Asbery Dickens assured Captain Richard Derly, USRCS, commanding the Revenue cutter Morris, that he had "permission of the department to employ free colored persons as cook and steward of the Morris."

Since 1794, the Revenue Marine Service had been carrying out the important mission of preventing importation of slaves into the territorial limits of the United States . Although the law of March 22, 1794, prohibiting the slave trade between the United States and foreign countries, did not specifically direct the revenue cutters to aid in its enforcement, "they were nevertheless instructed to do so; and their connection with efforts to suppress the traffic, begun under this Act, did not cease until the occasion for such efforts had entirely disappeared."

Illustrating this mission, the revenue cutters stationed at South Atlantic coast ports and operating under the authority of the Acts of March 2, 1807 and March 3, 1819, captured numerous vessels with almost 500 persons to be sold as slaves.

The following entry in the Service’s annual report for 1846 was typical: "Several captures of piratical vessels, which at the time infested the Florida keys, were made by Captain Jackson and others, and, having full cargoes of slaves destined for Amelia Island , were carried into American waters and confined."

While the status of African Americans in the United States was changed for all time by Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, the position of African Americans within the Revenue Cutter Service remained for the most part unchanged, with the dramatic exception of Captain Michael A. Healy.

CAPTAIN MICHAEL A. HEALY, U.S. REVENUE CUTTER SERVICE

Captain Michael A. Healy, the only African American to have a command or commission in any of the Coast Guard’s predecessor services, commanded the cutter Bear from 1887 to 1895. Healy retired as the third highest-ranking officer from the Revenue Cutter Service.

Captain Michael A. Healy, U.S. Revenue Cutter Service

[190515-G-G0000-3001]

One of ten children born in Macon, Georgia, to an Irish immigrant and a slave of mixed blood, Healy habitually ran away from school. At the urging of his brother, who felt sea life would discipline the youngster, the 15-year-old Healy was hired as a cabin boy abroad the clipper Jumna in 1855. He applied to and was accepted by the Revenue Cutter Service in March of 1865, was promoted to Second Lieutenant in June 1886, and to First Lieutenant in July 1870.

As First Lieutenant, Healy was ordered aboard the cutter Rush, to patrol Alaskan waters for the first time. He became known as a brilliant seaman and was considered by many the best sailor in the North. A feature article in the January 28, 1884 New York Sun stated: "Captain Mike Healy is a good deal more distinguished person in the waters of the far Northwest than any president of the United States or my potentate in Europe has yet become."

Healy distinguished himself when he took command of the cutter Bear, considered by many the greatest polar ship of its time, in 1886. The ship was charged with "seizing any vessel found sealing in the Bering Sea ." By 1892, the Bear, Rush and Corwin had made so many seizures that tension developed between the United States and British merchants. Healy was also tasked with bringing medical and other aid to the Alaska Natives, making weather and ice reports, preparing navigation charts, rescuing distressed vessels, transporting special passengers and supplies, and fighting violators of federal laws. He served as deputy U.S. Marshal and represented federal law in Alaska for many years.

On one of Bear’s annual visits to King Island , Healy found a native population reduced to 100 people and begging for food. After ordering food and clothing, Healy worked with Dr. Sheldon Jackson of the Bureau of Education to import reindeer from the Siberian Chukchi, another Eskimo population. During the next ten years, Revenue cutters brought some 1,100 reindeer to Alaska . The Bureau of Education took charge of landing and distributing the deer, and missionary schools taught the natives to raise and care for the animals. By 1940, Alaska ’s domesticated reindeer herds had risen to 500,000.

The Coast Guard named an icebreaker for Michael Healy, in acknowledgment of his inspiring commitment to the Service, including his invaluable assistance to Alaska Natives.

THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR: HEROES OF THE REVENUE CUTTER HUDSON

During the Spanish-American War, two African American cuttermen distinguished themselves at the Battle of Cardenas Bay in Cuba . On 11 May 1898 the Revenue Cutter Hudson , armed with two six-pounders, joined two U.S. Navy gunboats and a torpedo boat for a raid into the Spanish-fortified bay. Careful to avoid mines, three of the vessels moved into the channel, one gunboat provided supporting fire. Once inside the bay, they spotted their target. Hudson and the torpedo boat, USS Winslow, moved at full speed to attack the Spanish gunboats moored to the sugar wharves. The second Navy gunboat held back to support their attack with her 4-inch guns.

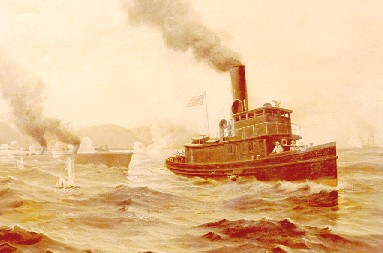

A painting of the Cutter Hudson in the Spanish-American War

[190515-G-G0000-9001]

Before they reached point-blank range, the Spanish shore batteries were hitting Winslow. Firing smokeless powder, the Spanish guns could only be located by their intermittent flashes. Meanwhile, the American gunners, hampered by smoke from their own black powder, returned fire. The Hudson alone fired 135 shells in just twenty minutes. Helping to sustain this rapid rate of fire was Hudson 's African American steward, Savage, who passed ammunition in a steady stream.

With advantages in position, cover, and visibility, the Spanish fired on the ships from five different directions with solid shot and shrapnel. "Shells screamed overhead and lashed the water all around," recalled one cutterman.

For almost half an hour Winslow escaped serious damage. Then two shells ripped into her. With a boiler and her steering engine wrecked, she began drifting toward the beach. The Spanish then concentrated their fire on her. Hudson now stood shoreward into the hail of the "very fierce" fire and to take Winslow into tow. When only 100 feet away, the cuttermen watched in horror as an exploding shell cut down four sailors waiting to catch the heaving line. Other hands caught the line and made it fast. With that Hudson began moving toward safety. "The sound, smoke, and smell of battle faded into the distance, into the past, leaving Cardenas the heat and humdrum of perpetual siesta, and to the Coast Guard, the remembered words, ‘ Cardenas Bay ."’

In his after-action report, Hudson 's Commanding Officer spoke highly of his men:

Each and every member of the crew from the boatswain down to Moses Jones, the colored boy who attached himself to the after gun and never failed to have a shell ready when it was needed, did his whole duty cheerfully and without the least hesitation. This appears more the remarkable in view of the fact that none of them had ever been under fire before, and that the guns were without protection or shelter of any kind. They deserve the most substantial recognition in the power of the Government for their heroic services upon this occasion.

The courage of the crew, including Steward Savage and Cook Moses Jones, was recognized by a joint resolution of Congress, acting upon the recommendation of President William McKinley:

In the face of a most galling fire from the enemy’s guns, the revenue cutter HUDSON, commanded by First Lieutenant Frank H. Newcomb, United States Revenue Cutter Service, rescued the disabled WINSLOW, her wounded commander and remaining crew. The commander of the HUDSON kept his vessel in the very hottest fire of the action, although in constant danger of going ashore on account of the shallow water, until he finally got a line fast to the WINSLOW and towed that vessel out of range of the enemy’s guns, a deed of special gallantry.

I recommend that, in recognition of the signal act of heroism of First Lieutenant prank H. Newcomb, United States Revenue Cutter Service, above set forth, the thanks of Congress be extended to him and to his officers and men of the HUDSON; and that a gold medal of honor be presented to Lieutenant Newcomb, and silver medal of honor to each of his crew who served with him at Cardenas.

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN THE U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SERVICE

Before construction of the first U.S. lighthouse in Boston , Massachusetts , in 1716, only bonfires or blazing barrels of pitch on headlands guided ships to port at night. Boston had one of America ’s earliest fog signals and the first buoys appeared in the Delaware River by 1767. The earliest Lightship Station was at Craney Island , Hampton Roads, Virginia , where a decked-over small boat was moored in 1820.

Responsibility for navigational aids was assumed by the Federal government in 1789. when the Lighthouse Service was part of the Treasury Department’s Revenue Marine Bureau. From 1852 to 1910, the responsibility for aids came under the rule of the Lighthouse Board, then shifted to the Commerce Department in 1903. The Service was a Commerce responsibility until it was returned to the Treasury and the Coast Guard.

The history of African Americans in the U.S. Lighthouse Service is sketchy. The first recorded mention of an African American was in 1718, when a slave who worked at the Boston Lighthouse perished with the keeper and his family during a storm. There are recorded instances of African Americans serving aboard early lightships as cooks, probably due to an 1835 regulation specifically forbidding the hiring of African Americans in other capacities. An elderly African American woman is described as tending the Simons Island Light in 1836, when the keeper was incapacitated by gout.

On a stormy March evening in 1847, an African American sailor knocked loudly on the tower door of the Isle of Shoals Lighthouse off the New Hampshire coast. He informed the assistant keeper that a brig was ashore on the rocks below the light. The keeper later learned that the sailor had faced almost certain death to get help for his shipmates. In 1852 the New Point Comfort Lighthouse in Virginia was run by a retired sea captain and his assistant, a woman slave.

A famous example of valor by an African American is that of the slave Assistant to the keeper of the Cape Florida Light on Key Biscayne, one of the oldest lighthouse towers in the United States . During the Seminole Indian Wars in 1836, Keeper John W.B. Thompson and his African American Assistant took refuge in the lighthouse, where they were besieged throughout the day and into the night. Musket shots at the attackers kept them from the tower until dark, when the Seminole Indians set fire to the door and the lowest plank-boarded window.

The flames were fierce, fed by yellow pine wood and oil cans punctured by the Indians’ shots, and the two men were driven to the top of the tower. The keeper cut away the stairs halfway up from the bottom and managed to confine the fire within the tower for a time by covering over the scuttle leading to the lantern. But the intense heat and flames drove the two men out of the lantern and down on the edge of a two-foot platform where they were nearly roasted alive.

Stretched out for momentary relief from cramping, the arms and legs of the victims were instant targets for the Indians’ shots from below. Gas from the flaming lantern burst in all directions. In desperation, Keeper Thompson threw a keg of gunpowder down the scuttle. It exploded instantly and shook the tower from top to bottom but failed to demolish the structure and the two men.

Shortly thereafter, the Assistant died of his wounds. As the keeper prepared to end his torture by jumping off the ledge, the fire fell to the bottom of the tower and a stiff breeze provided some relief. Assuming both men were dead, the Indians left the tower and set fire to the dwelling.

Severely burned and wounded, the keeper lay wounded far from the ground in an apparently hopeless position. He managed to make a signal from a piece of blood-soaked clothing that had not burned. Later in the day he sighted the schooner Motto and the sloop-of-war USS Concord, which had heard the explosion 12 miles off and had come to his assistance. After other rescue methods had failed, the rescuers fired twine from their muskets, fastened to a ramrod, with which the keeper managed to haul up a tail block and secure it to an iron stanchion. Two men were hoisted up and soon the keeper was lowered to the ground and given medical aid.

Thanks to the assistant who had given his life in defense of the lighthouse, and to the crews of Motto and Concord , Keeper Thompson, crippled for life, survived the harrowing experience. Rebuilding of the lighthouse after the Seminole attack was authorized in 1837. In 1855, the tower was raised to 95 feet. The lighting apparatus was destroyed in 1861 during the Civil War and was not restored until 1867.

The light continued to guide mariners as they passed the dangerous Florida Reef. On June 15, 1878, Fowey Rocks light was established and Cape Florida light was discontinued. The tower and property were sold in 1915 to the late James Deering of Chicago, Illinois . The structure where Keeper Thompson’s valiant Assistant died is carried in the current light list of the U.S. Coast Guard as "Cape Florida Daybeacon, white unused lighthouse tower, privately maintained."

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN THE LIFESAVING SERVICE

The African Americans employed by the Life-Saving Service were experienced fishermen and oystermen who had lived along the Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina Coasts. They were well-trained to handle boats and were knowledgeable of surf and sea. Upon clearance from the medical surgeon, these men were issued Articles of Engagements and became paid U.S. Life-Savers.

The crew of the Pea Island Life-Saving Station, ca. 1890; Keeper Richard Etheridge is on the far left.

[190515-G-G0000-3002]

Beginning around 1875, records show the presence of African Americans at the following Life-Saving Stations. In what is now the Fifth Coast Guard District: Portsmouth, Va. ; Station 3, Green Run, James H. Shields and Alexander Ames; Station 5, Cedar Island, A. Finney; Station 7, Cobbs Island, Warner Collins. The Sixth District appeared to employ many more African Americans during the mid-1870s than did the Fifth District. Station 1, Cape Henry, George Owens, William Olds, T. Cuffey, Luther Owens, and Peter Fuller; Station 4, Jones Hill and Jerry Munden; Station 7, Nags Head, William C. Bowser, Miles Tilett and George Reed; Station 8, Bodies Island, Fields Midgett, G.W. Bowser, Robert F. Toler and the renowned Richard Etheridge; Station 16, George R. Midgett, Lewis Westcott and King Daniel. Station 25, Cape Fear , John W. Smith, Robert Smith and Gibb McDonald.

These experienced seamen cooked, patrolled the beach, and participated in various duties that became integral to their work as surfmen. A typical Life-Saving Station day included such routines as cleaning the station, patrolling the beaches, drilling in the use of life cars, practicing launching of the station’s lifeboat, practicing with the breeches buoy, throwing a line (firing the gun) to a representation of a wreck, sanding and painting the boats, traveling to pick up mail and supplies, practicing resuscitation or repairing equipment.

The primary duty of crews at Life-Saving Stations was to aid ships in distress . African Americans saved many lives and preserved property in so doing. The story of Richard Etheridge, first African American keeper of Pea Island , North Carolina Lifeboat Station, is an inspiring first chapter in the celebrated history of the lifeboat station that was built during the winter of 1878-79 and initially manned by whites. From the time of Etheridge’s assuming command in 1880, Pea Island was staffed by African Americans until the station was closed in 1947, after which the area became a wildlife refuge.

Pea Island LBS crew, circa 1942.

Pea Island Lifeboat Station logged numerous rescues in its annals. One of the early crewmembers of the Pea Island Station, Maxie Berry, Sr., served 25 years and retired as a chief Boatswain’s Mate. His father, Joseph H. Berry, Surfman, retired in 1917 after 15 years of service at Pea Island. Maxie Berry’s son, Maxie M. Berry, Jr., retired as a Coast Guard Lieutenant Commander on September 1, 1976, while stationed in the Office of Civil Rights at Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington , D.C. Another son of the late Maxie Sr., Zion H. Berry, also served in the Coast Guard, to continue a remarkable tradition of over 350 years of continuous service.

RICHARD ETHERIDGE: KEEPER, PEA ISLAND LIFE-SAVING STATION

The majority of published information on the Life-Saving Service celebrates the accomplishments of the all-African American crew at Pea Island Life-Saving Station in North Carolina. In 1879, Charles F. Shoemaker, Assistant Inspector of the Life-Saving Service, recommended Richard Etheridge to assume keepership at Pea Island, following the discharge of the previous keeper and surfman, whose failures in performance of duty resulted in unnecessary loss of life after the wreck of the Henderson . Shoemaker’s letter of recommendation to Summer I. Kimball, then General Superintendent of the Life-Saving Service, read, in part:

I examined this man, and found him to be 38 years of age, strong, robust physique, intelligent and able to read and write. He is reputed one of the best surfmen on this part of the coast of North Carolina.

Shoemaker recommended that Etheridge select a crew of African Americans, two from stations No. 10, two already at Pea Island (W.B. Daniels and W.R. Davis) and two others of Etheridge’s choosing. Adding that he was "aware that no colored man holds the position of Keeper in the Life-Saving Service," Shoemaker explained that Etheridge was such an excellent surfman that "the efficiency of the Service at [ Pea Island the station will be greatly enhanced." Frank Newcomb, Assistant Inspector of the Life-Saving Service, also recommended Etheridge to Kimball. Shoemaker endorsed Newcomb’s letter, which included the comment that Etheridge "had the reputation of being as good a surfman as there is on this coast, Black or White."

Appointed Keeper of Pea Island Life-Saving Station on January 24, 1880, Richard Etheridge became the first African American keeper in the Service. He was born in 1842 and raised near Pea Island , where he became an expert fisherman and surfman. Soon after Etheridge’s appointment, the station burned down. Determined to execute his duties with expert commitment, Etheridge supervised the construction of a new station on the original site. He also developed rigorous lifesaving drills that enabled his crew to tackle all lifesaving tasks. His station earned the reputation of "one of the tautest on the Carolina Coast," with its keeper well-known as one of the most courageous and ingenious lifesavers in the Service.

On October 11, 1896, Etheridge’s rigorous training drills proved invaluable. The three-masted schooner, the E. S. Newman, was caught in a terrifying storm. En route from Providence , Rhode Island to Norfolk, Virginia, the vessel was blown south, 100 miles off course, and slammed onto the beach two miles south of the Pea Island Station. The storm was so severe that Etheridge had suspended normal beach patrol that day. But the alert eyes of surfman Theodore Meekins saw the first distress flare and Meekins immediately notified Etheridge.

The crew was rounded up and launched the surfboat. Battling the strong tide and sweeping currents, the dedicated lifesavers struggled to make their way to a point opposite the schooner, only to find there was no dry land. The daring, quick-witted Etheridge tied two of his strongest surfmen together and connected them to shore by a long line. They fought their way through the roaring breaks and finally reached the schooner. The seemingly inexhaustible Pea Island crewmembers journeyed through the perilous waters ten times and rescued every one of the nine persons on board. For this action the Pea Island Life-Saving Station was awarded the Gold Life-Saving Medal. On February 29, 1992, the Coast Guard Cutter Pea Island was commissioned at Norfolk, Virginia, in memory of the African American crews at Pea Island , including Richard Etheridge and his lifesavers.

AFRICAN AMERICAN COAST GUARDSMEN IN DEFENSE OF AMERICA

The Coast Guard has served in every war from the American Revolution through the Persian Gulf Conflict. During World War I, 15 Coast Guard cutters, some 200 officers and 5,000 enlisted men went into action as part of the U. S. Navy. By World War II, the Coast Guard had 802 vessels, and its personnel manned 351 Navy and 288 Army craft. Shore stations increased from 1,096 to 1,774, and by the end of the War, Coast Guard personnel numbered 171,168.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt made clear that African Americans would be integrated into the general ranks of the Coast Guard and Navy, Secretary of the Navy Knox announced in April1942 that African Americans would be accepted in capacities other than messmen. The first group of 150 African American volunteers was recruited and sent to Manhattan Beach Training Station in New York in the spring of 1942. Here, they received instruction in seamanship, knot typing, lifesaving and small-boat handling. Classes and other official activities were integrated, with sleeping and mess facilities still segregated. African Americans who qualified for specialized training after the four-week basic course became radiomen, pharmacists, yeomen, coxswains, electricians, carpenters’ boatswains 2nd mate.

Organized induction and assignment of a limited number of African American volunteers was terminated in December, 1942, when President Roosevelt ended volunteer enlistment of most military personnel. For the remainder of the World War II, the Coast Guard came under the Selective Service Law, which included a racial quota system.

Many African Americans continued to be assigned to steward duties and were often ordered to serve at important battle stations. The majority were assigned to shore duty, including security and labor details and working as yeomen, storekeepers, and in other capacities. The second all-African-American station (Pea Island was the first) was organized at Tiana Beach, New York. Other African Americans served on horse and dog patrols as lookouts for enemy infiltration along the coast.

CBM Cecil B. Foster, O.I.C of Coast Guard Lifeboat Station Tiana from 1942-1944

[190515-G-G0000-3004]

With so many African Americans assigned to shore duty, manpower planners found it difficult to rotate white Coast Guardsmen from sea to shore duty without transferring African Americans to cutters, which would result in integrating the vessels. In June 1943, LT Carlton Skinner proposed that a group of African American seamen receive practical seagoing experience in a completely integrated operation. The Commandant agreed and LT Skinner was promoted to LCDR and assigned to the weather ship USS Sea Cloud (IX-99) as her commanding officer. He had an integrated crew of 173 officers and men, of whom four officers and 50 petty officers were African American.

USS Sea Cloud (IX-99)

[190515-G-G0000-1001]

Prominent among them was the world-recognized American painter, Combat Artist PO3/c Jacob Lawrence, whose work is represented in the collections of The Smithsonian Institution, The Museum of Modern Art, Chicago Art Museum, and the Vatican Gallery. Jacob’s work has hung in the White House, and he has been featured on a Time cover, in an article in Fortune, and in many contemporary art books. Drafted into the US Coast Guard in October, 1943, Lawrence was given a Steward’s Mate rating. Upon assignment to the Sea Cloud, he obtained the rating of Public Relations (PR) PO3/c and was assigned the painting of documentary works of Coast Guard life.

Honored along with Paul Robeson, Duke Ellington, and W.E.B. DuBois by New Masses magazine, Lawrence is currently Professor Emeritus of Art at the University of Washington, Seattle . Although Sea Cloud was decommissioned in November 1944, its year of operation demonstrated that no racial incidents occurred and that the integrated crew was in every way as efficient as any other. The experiment paved the way for other African Americans to serve in crews not completely segregated. During World War II, the other Coast Guard vessel with a significant degree of integration was the frigate USS Hoquiam (PF-5), operating out of Adak in the Aleutian Islands during 1945.

A well-known example of African American military expertise was the crew of stewards that manned a battle station on the cutter Campbell (WPG-32) which rammed and sank a German submarine on February 22, 1943. Louis Etheridge, Captain of the African American gun crew, was presented the bronze medal on February 25, 1952, and a personal letter of congratulations from the Commandant. The crew earned medals for "heroic achievement."

One African Americans who died in the line of duty is Charles W. David, Jr., a messman aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Comanche (WPG-76) that came to the aid of a torpedoed transport in the North Atlantic. David repeatedly dived overboard to rescue several men. LT Langford Anderson, executive officer of the cutter, was the last man rescued by David, before he lost his life attempting to save others.

As the war progressed, African Americans advanced into the petty officer ranks. By August 1945, 965 African Americans were petty officers or warrant officers, often in the general services. Many of these officers worked at shore stations and served as instructors at Manhattan Beach, the customary commissioning source for African Americans.

Receiving commissions were Joseph Jenkins, who went from Manhattan Beach to Officer Candidate School (OCS) at the Coast Guard Academy. Jenkins graduated as the first African American Ensign in the Coast Guard Reserve in April 1943, almost a full year before African Americans were commissioned in the Navy. Harvey C. Russell assigned to the Hoquiam, located in the Philippines to serve as executive officer on a cutter in the Philippines, there he assumed responsibility of a racially integrated vessel shortly after the war. Clarence Samuels, a warrant officer, was commissioned as a LTJG and assigned to the Sea Cloud.

Joseph Jenkins and Clarence Samuels aboard the Sea Cloud, 1944.

[190515-G-G0000-3005]

The Coast Guard was the first service to accept women into its academy and the first to assign them as commanding officers of armed vessels and air stations. Service by women in the Coast Guard goes back 50 years. The Coast Guard Women’s Reserve began in November 1942 during World War II.

SPAR recruits Julia Mosley (left) and Daisy Winifred Byrd (right).

[190515-G-G0000-3006]

In the fall of 1944 the Coast Guard recruited five African American women as reservists, four weeks after it was announced that the recruitment of women, except for replacements, would be stopped November 23, 1944.

Now fully integrated, the Coast Guard utilized African American personnel in every capacity during the Vietnam War. No longer are African American personnel limited from serving as integral team members in wartime or in the Coast Guard’s many peacetime humanitarian missions.

CHIEF JOURNALIST ALEX P. HALEY, 1921-1992

Born in Ithaca, New York, August 11, 1921, Alex P. Haley graduated from high school at 15, attended State Teacher’s College in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, for two years and, at the urging of his father, enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1939 as a steward, assisting cooks. Steward was the only rank in which most African Americans could enter the Coast Guard at the time Haley enlisted. During his years of service Haley developed and honed the writing skills that made him the first Coast Guard journalist. He continued to write the worldwide best seller Roots, which received the 1977 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X based on Haley’s extensive conversations with the former chief spokesman for the Nation of Islam.

Alexander Haley

[190513-G-G0000-2002]

Serving as ship’s cook in the Pacific during World War II, Haley spent most of his Coast Guard duty in long months at sea. While at sea on the cutter Mendota, Haley took up letter writing, and in one week could knock out 40 letters and receive just as many replies. His mail-call success prompted shipmates to enlist his help with their letters, including love letters.

During his time at sea on various cutters, Haley set down sea stories recounted by old salts aboard. Eight years and hundreds of rejection slips later, he had his first story published. In 1944, Haley was assigned to edit "Out Post," the official Coast Guard Publication. In 1945 he won the Ship’s Editorial Association Award and served as assistant to the public relations officer at Coast Guard headquarters until 1959.

Haley transferred to the journalist rate in 1949 and was the first Coast Guardsman to attain the rank of chief petty officer in that rate when the Coast Guard promoted him in 1950. His primary job was writing stories to promote the Coast Guard to the media. Toward the end of his tenure with the Coast Guard, Haley researched and wrote about the history of the Coast Guard’s Revenue Cutter Service and the Life-Saving Service, which demonstrated the talent that would make him a famous journalist and author. His ability to transform meticulous research into informative, interesting narrative became his trademark.

Chief Journalist Alexendar Haley after his promotion.

[190513-G-G0000-3005]

After 20 years of service, Haley retired as Chief Journalist in 1959 after serving in World War II and Korea . He never forgot the Coast Guard, and the Coast Guard never forgot one of its more accomplished veterans. Their paths continued to cross as Haley spoke at various Coast Guard functions. Haley said of the Coast Guard, "You don’t spend twenty years of your life in the service and not have a warm, nostalgic feeling left in you. It’s a small service, the Coast Guard, and there is a lot of esprit de corps."

After retiring from the Coast Guard, Haley continued to write professionally, including articles for Reader’s Digest and Playboy ,and best-selling books and TV mini series. Roots has been translated into 37 languages and sold 6 million copies in hardcover and millions more in paperback. The blockbuster television mini-series "Roots: The Saga of an American Family," was broadcast on ABC in 1977 and was watched by an estimated 130 million viewers.

Since his Coast Guard days, Haley completed much of his writing at sea. He wrote A Different Kind of Christmas, the story of a slave’s escape on the Underground Railway, during a freighter voyage from Long Beach , California to Australia . In 1973 Haley was presented with the Distinguished Public Service Award and a citation from Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard Admiral Bender and Rear Admiral John F. Thompson, Superintendent of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. Haley worked to promote literacy and participated in programs that encouraged young people to remain in school. To this day, thanks to the famous Coast Guard veteran, eight students, selected on the basis of economic need, not race, are supported from freshman year through graduate school by Alex Haley’s scholarship fund.