Nov. 12, 2021 —

Prohibition was an era of illicit liquor, bootleggers, and adventure on the high seas, most notably on the East Coast. It became illegal to produce, sell, or transport liquor for consumption on Jan. 17, 1920. The United States Coast Guard had its share of the action searching for bootleggers offshore and along the U.S. coastline and inland waters.

Prohibition was an era of illicit liquor, bootleggers, and adventure on the high seas, most notably on the East Coast. It became illegal to produce, sell, or transport liquor for consumption on Jan. 17, 1920. The United States Coast Guard had its share of the action searching for bootleggers offshore and along the U.S. coastline and inland waters.

On a rainy evening, the CG-289 was on patrol. Stationed at New London, Conn., the cutter patrolled Long Island Sound and the coast of New York. As dusk fell, bootlegging activity increased, since the darkness made it easier for rumrunners to transfer contraband from mother ships to shore bases. Cutter CG-289’s skipper, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Harold Tantaquidgeon, picked up his binoculars and surveyed the water for suspicious movements. He spied two large powerboats, one with its lights off. Thinking they might be rumrunners, Tantaquidgeon quietly followed the two boats toward the ocean, where they suddenly parted ways. Tantaquidgeon ordered CG-289’s lights turned off and continued to follow the lighted boat.

At some point, the lighted boat went dark, forcing CG-289 to idle until Tantaquidgeon saw a flicker of lights signaling the transfer of contraband from a mother ship to the boat. Ordering his crew to pursue the dark boat, Tantaquidgeon turned on his searchlights, and Last Chance was caught dead center in the beams. Last Chance quickly took off, with CG-289 in pursuit and firing  shots at the rumrunner. Eventually, Last Chance gave up and its skipper allowed Tantaquidgeon and his crew to board the boat. “What cargo do you have on board?” asked Tantaquidgeon. “I’m a fisherman. We’re loaded with fish,” responded the skipper of the boat.

shots at the rumrunner. Eventually, Last Chance gave up and its skipper allowed Tantaquidgeon and his crew to board the boat. “What cargo do you have on board?” asked Tantaquidgeon. “I’m a fisherman. We’re loaded with fish,” responded the skipper of the boat.

Tantaquidgeon was skeptical. He ordered a search of the boat. Opening one hatch, he and his crew were overtaken by the stench of a mountain of decaying fish. However, Tantaquidgeon knew that the rotting cargo could be hiding illegal liquor. He ordered his men to throw the fish overboard and discovered a large cache of vintage World War I whiskey protected by tarpaper. Cutter CG-289 towed Last Chance back to the New London State Pier, where government agents seized the vessel and arrested its crew. Tantaquidgeon later testified against them in federal court.

All in a day’s work b y a Coast Guard patrol boat during Prohibition, just one of several hundred such boats in the Prohibition fleet. While this event typifies Coast Guard patrols during the Prohibition era, Tantaquidgeon was an exceptional figure both as one of the few Native Americans in the Coast Guard and the first to achieve the rank of chief boatswain’s mate in the service.

y a Coast Guard patrol boat during Prohibition, just one of several hundred such boats in the Prohibition fleet. While this event typifies Coast Guard patrols during the Prohibition era, Tantaquidgeon was an exceptional figure both as one of the few Native Americans in the Coast Guard and the first to achieve the rank of chief boatswain’s mate in the service.

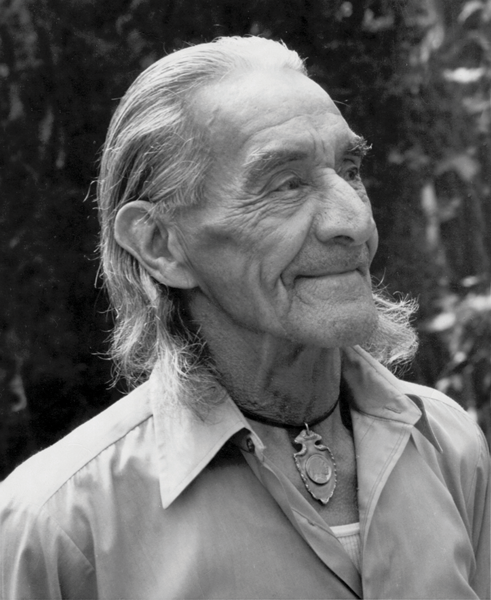

Born on June 18, 1904, in Mohegan, Conn., Tantaquidgeon was the fourth of seven children of John Tantaquidgeon and Harriet Fielding and a citizen of the Mohegan Tribe. He was a descendant of Uncas, sachem (leader) of the Mohegan Tribe. The town of Uncasville, Conn., is named for Uncas, who allied with the first white settlers in 17th-century Connecticut.

The Mohegan lands were quite vast during Uncas’ time, but had dwindled considerably by the time Tantaquidgeon was born. The first Tantaquidgeon (loosely translated to “He Who Runs Fast”) of notable fame was a warrior and athlete. Harold’s great-grandfather, simply known as Old Man Tantaquidgeon, served on the schooner Putnam during the American Revolution. His father’s older brother, “Uncle Edwin,” was a whaler on Pequot, which sailed out of New London around Cape Horn and into the Pacific Ocean hunting sperm whales.

Young Harold’s formal education ended when he completed the eighth grade. After that, everything he learned came from his father—basket weaving, forging knife blades, assembling a gun, capture and sale of wild animals and wilderness survival skills. When World War I broke out, Tantaquidgeon was too young to enlist, so he joined the Home Guard at Norwich, Conn. Every time he travelled through New London, he spent time at the Coast Guard docks studying the cutters. By the time the war ended, Tantaquidgeon had decided his fate was with the Coast Guard.

Young Harold’s formal education ended when he completed the eighth grade. After that, everything he learned came from his father—basket weaving, forging knife blades, assembling a gun, capture and sale of wild animals and wilderness survival skills. When World War I broke out, Tantaquidgeon was too young to enlist, so he joined the Home Guard at Norwich, Conn. Every time he travelled through New London, he spent time at the Coast Guard docks studying the cutters. By the time the war ended, Tantaquidgeon had decided his fate was with the Coast Guard.

The opportunity to enlist materialized in 1921, when Tantaquidgeon was 17 years old. A friend paid him a visit at the Tantaquidgeon family farm, where Harold and his father were splitting logs. There was a vacancy on the Coast Guard cutter Pequot, an old fishing boat being fitted-out as a cable-laying vessel in New London. Tantaquidgeon saw this as a symbolic opportunity, not only because the Mohegans were once part of the Pequot people, but also because it reminded him of all the stories his Uncle Edwin had told of his days on Pequot. Before packing his things and signing up, young Tantaquidgeon’s father had him finish splitting the logs!

Stepping off the train at New London, Tantaquidgeon went to the U.S. Customs House and told a recruiting officer that he wanted to join the United States Coast Guard and serve aboard Pequot. After he enlisted and boarded the vessel, the Coast Guard crew took quite an interest in him, as they had never seen a Native American, much less a man with long hair. Initially nicknamed Tomahawk by his fellow crew, he was eventually simply known as Tom. Interestingly enough, his Coast Guard service record is filed under the name “Quidgeon.”

wanted to join the United States Coast Guard and serve aboard Pequot. After he enlisted and boarded the vessel, the Coast Guard crew took quite an interest in him, as they had never seen a Native American, much less a man with long hair. Initially nicknamed Tomahawk by his fellow crew, he was eventually simply known as Tom. Interestingly enough, his Coast Guard service record is filed under the name “Quidgeon.”

Pequot’s mission was to lay and repair underwater telegraph cables. It did so along the East and Gulf coasts, from Lubec, Maine, to Galveston, Texas. Along this area of responsibility, it answered calls for assistance from lighthouses and remote islands. Tantaquidgeon advanced to seaman first class after two years on Pequot. After serving for a year, he was home on leave, and received the news that Pequot was to be decommissioned.

On the way to Norfolk, Virginia, to report for duty, Tantaquidgeon imagined Pequot II to be a shiny, top of the line Coast Guard vessel. He was disappointed to discover that the cable-laying vessel was a converted Navy mine planter from World War I and, as soon as he reported, the vessel began to take on water and sink. Someone had left open the coal chutes as the vessel took on coal and settled lower in the water. Luckily, it was salvaged and ready to sail by the next day. Tantaquidgeon spent the next two years on board Pequot II—first in its engine room and then the radio room. Finally, he advanced to quartermaster assisting the navigator in the pilothouse and overseeing the vessel’s charts, flags and signalmen.

When Pequot II was in p ort, Tantaquidgeon heard stories of the rumrunners and decided he wanted a piece of the action. He applied for a transfer to one of the Coast Guard’s new 75-foot cutters. By then, chief boatswain’s mates were put in charge of these so-called “six-bitters,” because the number of new cutters outnumbered the service’s commissioned officer ranks. Tantaquidgeon was just 23 years old in 1927 when he became one of the youngest chief petty oficers in the service history. However, he was still known as “the Old Man” to his younger crew of eight aboard the 75-foot cutter CG-289. Tantaquidgeon remained on CG-289 until he left the service in 1930. He received an honorable discharge and returned home to Connecticut.

ort, Tantaquidgeon heard stories of the rumrunners and decided he wanted a piece of the action. He applied for a transfer to one of the Coast Guard’s new 75-foot cutters. By then, chief boatswain’s mates were put in charge of these so-called “six-bitters,” because the number of new cutters outnumbered the service’s commissioned officer ranks. Tantaquidgeon was just 23 years old in 1927 when he became one of the youngest chief petty oficers in the service history. However, he was still known as “the Old Man” to his younger crew of eight aboard the 75-foot cutter CG-289. Tantaquidgeon remained on CG-289 until he left the service in 1930. He received an honorable discharge and returned home to Connecticut.

Tantaquidgeon’s father had, for many years, collected Indian artifacts with the hope of opening a museum, but waited until his son had completed his service. The Tantaquidgeon Museum formally opened in 1931 in Uncasville and is still in existence. Tantaquidgeon became a pillar of the museum, lecturing on Indian lore and teaching children about Mohegan traditions. He developed a close relationship with the Boy Scouts, teaching them survival skills at Camp Wakenah, where he was known as Chief Tom Hat—derived from his initials, “H.A.T.,” carved into a knife made for him by his father. Tantaquidgeon carried the knife everywhere he went for many years, including during his Coast Guard service.

During World War II, Tantaquidgeon joined the U.S. Army’s 5th Air Force becoming a gunner with the 418th Night Fighter Squadron. On July 27, 1944, his plane was shot down over a swamp in New Guinea. When it crash-landed, he was thrown out of the plane but not injured. Because of his knowledge of survival skills, Tantaquidgeon and his crew of four survived the 23 days they were missing. For this, he was commended for distinguished service.

Tantaquidgeon never married, claiming he could not find a bride from the same tribe with the same deep values he held. He and his sister, Gladys, known for her pioneering work in Indian affairs and ethnobotany, lived the rest of their lives on the Tantaquidgeon farm, next door to the museum. Tantaquidgeon passed away on April 4, 1989, at the age of 84.