Oct. 22, 2021 —

Captain Satterlee was a particularly competent and efficient officer and made a record of which the best might well be proud.

“Official Record of Charles Satterlee,” Coast Guard Personnel Office, October 18, 1918

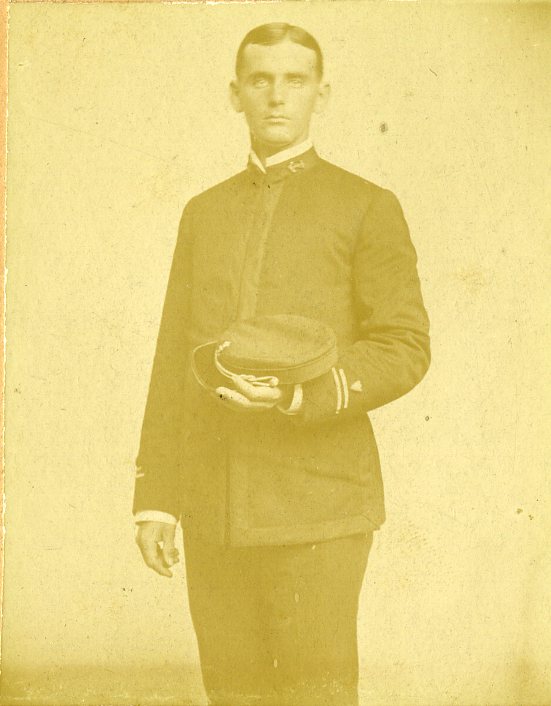

Charles Satterlee was born in Esse x, Connecticut, in 1875. His naval career began after completing the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service’s candidate entranc

x, Connecticut, in 1875. His naval career began after completing the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service’s candidate entranc e examination and taking the subscribed oath. On Nov. 19, 1895, he received an appointment as a cadet in the Revenue Cutter Service’s School of Instruction, and reported aboard the school ship Salmon P. Chase at New Bedford, Massachusetts.

e examination and taking the subscribed oath. On Nov. 19, 1895, he received an appointment as a cadet in the Revenue Cutter Service’s School of Instruction, and reported aboard the school ship Salmon P. Chase at New Bedford, Massachusetts.

On Jan.17, 1898, Senior Cadet Charles Satterlee graduated first in his class and, upon being commissioned a third lieutenant, was assigned to serve aboard the Revenue Cutter Woodbury in Portland, Maine. On April 25, 1898, Congress declared war with Spain and, not long after, President William McKinley directed the temporary transfer of certain Revenue Cutters to operate with the U.S. Navy as part of the Auxiliary Naval Force. The Navy re-designated Revenue Cutter Woodbury as the USS Woodbury and assigned it to the Navy’s North Atlantic Squadron. The Woodbury blockaded the port of Havana, Cuba, and braved enemy fire until the cessation of hostilities on Aug. 13th, when the Woodbury returned to the Treasury Department by executive order.

During the years 1900 to 1915, Satterlee served a tour of duty ashore as assistant inspector of U.S. Life-Saving Stations and on numerous cutters. After the Woodbury, Satterlee travelled to the west to serve aboard a succession of famed Bering Sea Patrol cutters, including the Corwin, Grant, Bear and Rush. His commanding officer aboard Grant, Capt. Dorr Tozier, wrote of Satterlee:

It is an unqualified pleasure for  me to state that Mr. Satterlee has performed every duty assigned him under my command with an intelligence rarely experienced in my service of more than thirty-five years, and I deeply regret his detachment from this vessel, and earnestly hope that he may be assigned to my command in the near future.

me to state that Mr. Satterlee has performed every duty assigned him under my command with an intelligence rarely experienced in my service of more than thirty-five years, and I deeply regret his detachment from this vessel, and earnestly hope that he may be assigned to my command in the near future.

In 1904, Satterlee returned to the East Coast to serve once more aboard the Woodbury. In 1906, he was promoted to first lieutenant and received his first afloat command, the Seminole stationed in Wilmington, North Carolina. After Seminole, he received a series of cutter commands, including the Mackinac, station ed in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and, in 1909, he was ordered to the newly-built cutter Tahoma. He commanded Tahoma on its globe circling maiden cruise from Baltimore to the West Coast by way of the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean. After delivering Tahoma to its new homeport of Port Townsend, Washington, he received command of Cutter Acushnet out of Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

ed in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and, in 1909, he was ordered to the newly-built cutter Tahoma. He commanded Tahoma on its globe circling maiden cruise from Baltimore to the West Coast by way of the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean. After delivering Tahoma to its new homeport of Port Townsend, Washington, he received command of Cutter Acushnet out of Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

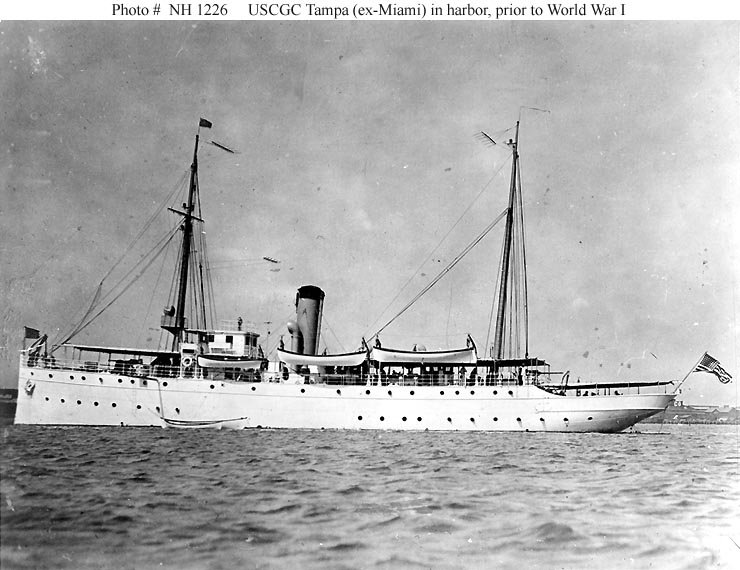

In Sept. 1915, while assigned to Acushnet, Satterlee was promoted to the rank of captain. Within months, he received command of the cutter Miami, recently constructed as a high seas “derelict destroyer.” The cutter’s name was subsequently changed to “Tampa” to reflect its close ties to its homeport in Florida. During his first years in command of Tampa, the cutter supported in the Coast Guard’s unique mission of tracking icebergs as part of the International Ice Patrol.

Shortly after the United States’ April 1917 declaration of war with Imperial Germany, the Coast Guard Cutters Algonquin, Ossipee, Manning, Seneca and Tampa were ordered to serve under the U.S. Navy. The cutters were refitted and assigned to operate as escorts for Allied merchant and military convoys from the island base of Gibraltar.

Shortly after the United States’ April 1917 declaration of war with Imperial Germany, the Coast Guard Cutters Algonquin, Ossipee, Manning, Seneca and Tampa were ordered to serve under the U.S. Navy. The cutters were refitted and assigned to operate as escorts for Allied merchant and military convoys from the island base of Gibraltar.

On Nov. 4, 1917, after Tampa’s arrival at U.S. Naval Base Nine at Gibraltar, the cutter commenced its first escort mission. Over the next 11 months, Tampa served as escort to 18 convoys, comprising 420 merchant vessels losing only two ships to U-boat attack. On Sept. 16, 1918, the Navy awarded Tampa the pennant for outstanding escort duty. The following day, having been assigned as escort to its 19th convoy, Tampa sailed at 1:00 p.m., from Gibraltar bound for Liverpool, England.

During the second day of the voyage the commodore of the convoy received a “secret” wireless transmission from the British Admiralty. At the time, an outward-bound convoy was assembling at Milford Haven, Wales, for a return voyage to Gibraltar with Tampa scheduled as an escort. The wireless message stated that “The destination of USS “TAMPA” is Milford [Haven] and she should be so informed. She should detach herself from the Convoy when in the vicinity of Milford.”

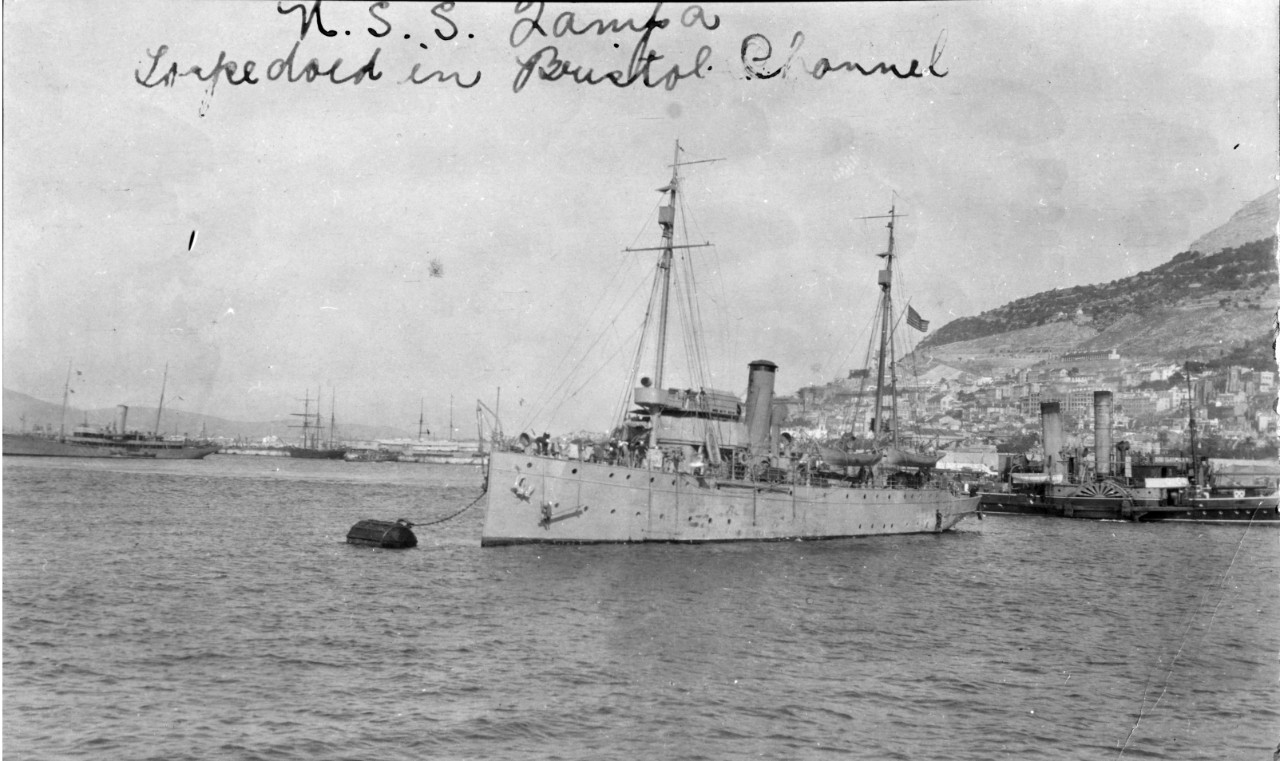

On Thursday, Sept. 26th, Capt. Satterlee officially requested and then received permission to detach Tampa from the convoy when his vessel was  near the Isles of Scilly, off Cornwall, England. Satterlee announced Tampa’s departure position at 4:15 p.m., and proceeded alone on a course for Milford Haven. A short time later, the shock of an explosion was felt by several units in the convoy. American destroyers and British patrol craft conducted a three-day search of Tampa’s last known position, but found only two unidentified bodies and some wreckage identified as Tampa’s.

near the Isles of Scilly, off Cornwall, England. Satterlee announced Tampa’s departure position at 4:15 p.m., and proceeded alone on a course for Milford Haven. A short time later, the shock of an explosion was felt by several units in the convoy. American destroyers and British patrol craft conducted a three-day search of Tampa’s last known position, but found only two unidentified bodies and some wreckage identified as Tampa’s.

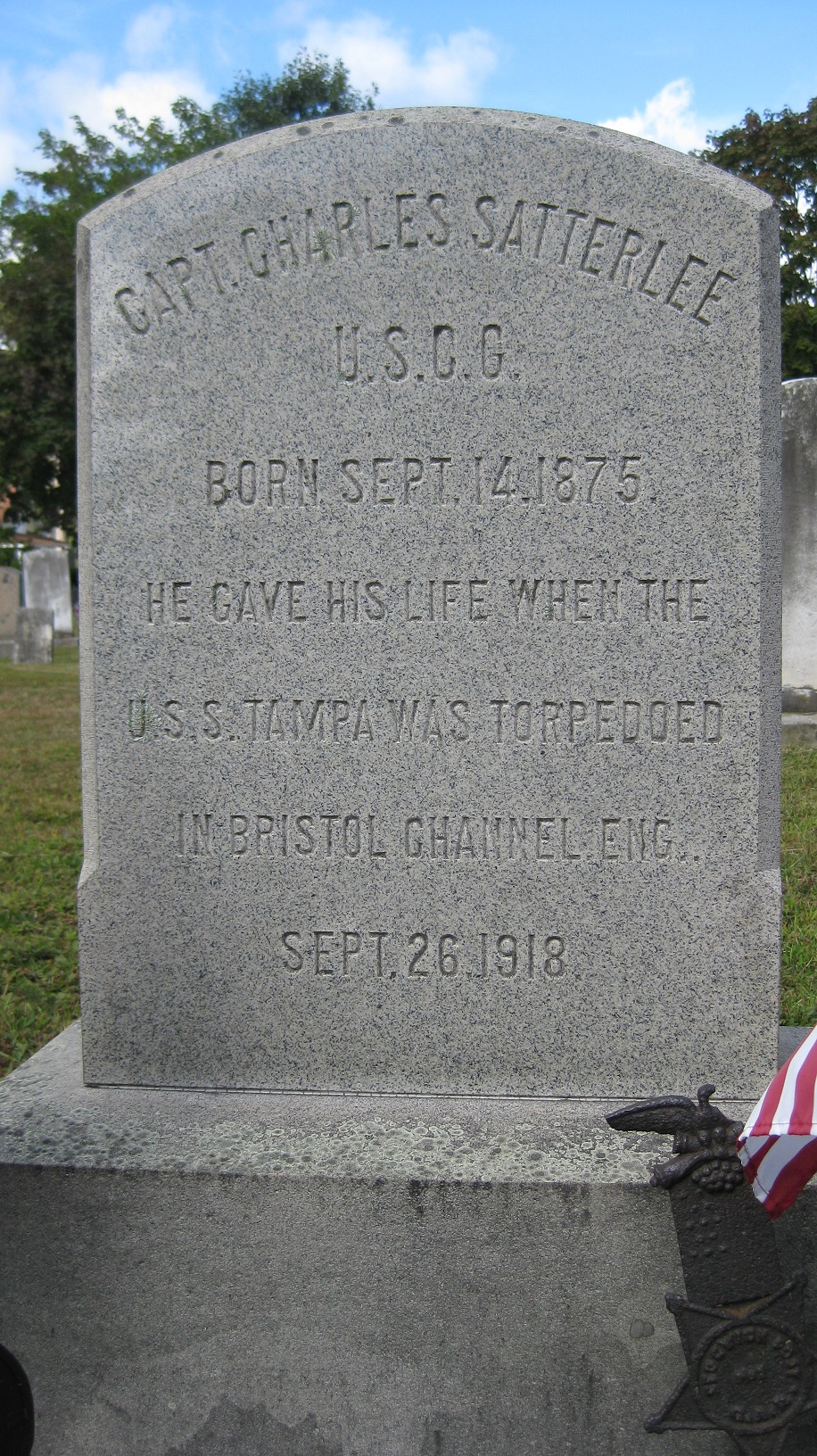

The sinking of the Tampa proved the worst combat loss suffered by U.S. naval forces during World War I. At the time of his death, Captain Charles Satterlee was 43 years old. For his meritorious service in World War I, the Navy awarded him the Distinguished Service Medal, one of the highest honors bestowed by the Navy at that time. The U.S. Navy also honored Satterlee as the namesake of a new destroyer and, later, as namesake of a World War II destroyer. Satterlee’s remains were never recovered; however, memorials honor him at the American Military Cemetery in Brookwood, England; Arlington National Cemetery; as well as a headstone at Gales Ferry Cemetery in his hometown of New London, Connecticut.

On Veteran’s Day, November 11, 1999, at the Coast Guard’s World War I Memorial located at Arlington National Cemetery, after the wreath-laying ceremony to honor veterans, Treasury Secretary Rodney Slater and Commandant James Loy presented to Tampa’s next-of-kin posthumous Purple Heart Medals for their lost loved ones. However, at that time, no living relatives could be found for Satterlee.

On Veteran’s Day, November 11, 1999, at the Coast Guard’s World War I Memorial located at Arlington National Cemetery, after the wreath-laying ceremony to honor veterans, Treasury Secretary Rodney Slater and Commandant James Loy presented to Tampa’s next-of-kin posthumous Purple Heart Medals for their lost loved ones. However, at that time, no living relatives could be found for Satterlee.

In October 2011, Coast Guard Commandant Robert Papp approved the presentation of Captain Satterlee’s posthumous Purple Heart Medal to Lyn Morgan Lawson, Satterlee’s second cousin. The ceremony was held on Saturday, May 12, 2012, at the Coast Guard Academy Museum. Four relatives of Captain Satterlee were present when Academy Superintendent, Rear Admiral Sandra Stotz, opened the ceremony with the reading of the Certificate of the Award followed by the presentation of Captain Satterlee’s posthumous Purple Heart Medal to Lawson.

On behalf of the Satterlee family, Ms. Lawson presented Captain Satterlee’s Purple Heart Medal to the Admiral for perpetual safekeeping and exhibition at the Academy Museum. Lawson later noted, “It was a proud moment for me, to be related to such a man.” She explained that, for herself and the family, it had been a perfect ceremony, especially since her niece Lt. Chelsea Smith Kalil, was able to attend as the family’s singular Coast Guard Academy graduate.