Oct. 15, 2021 —

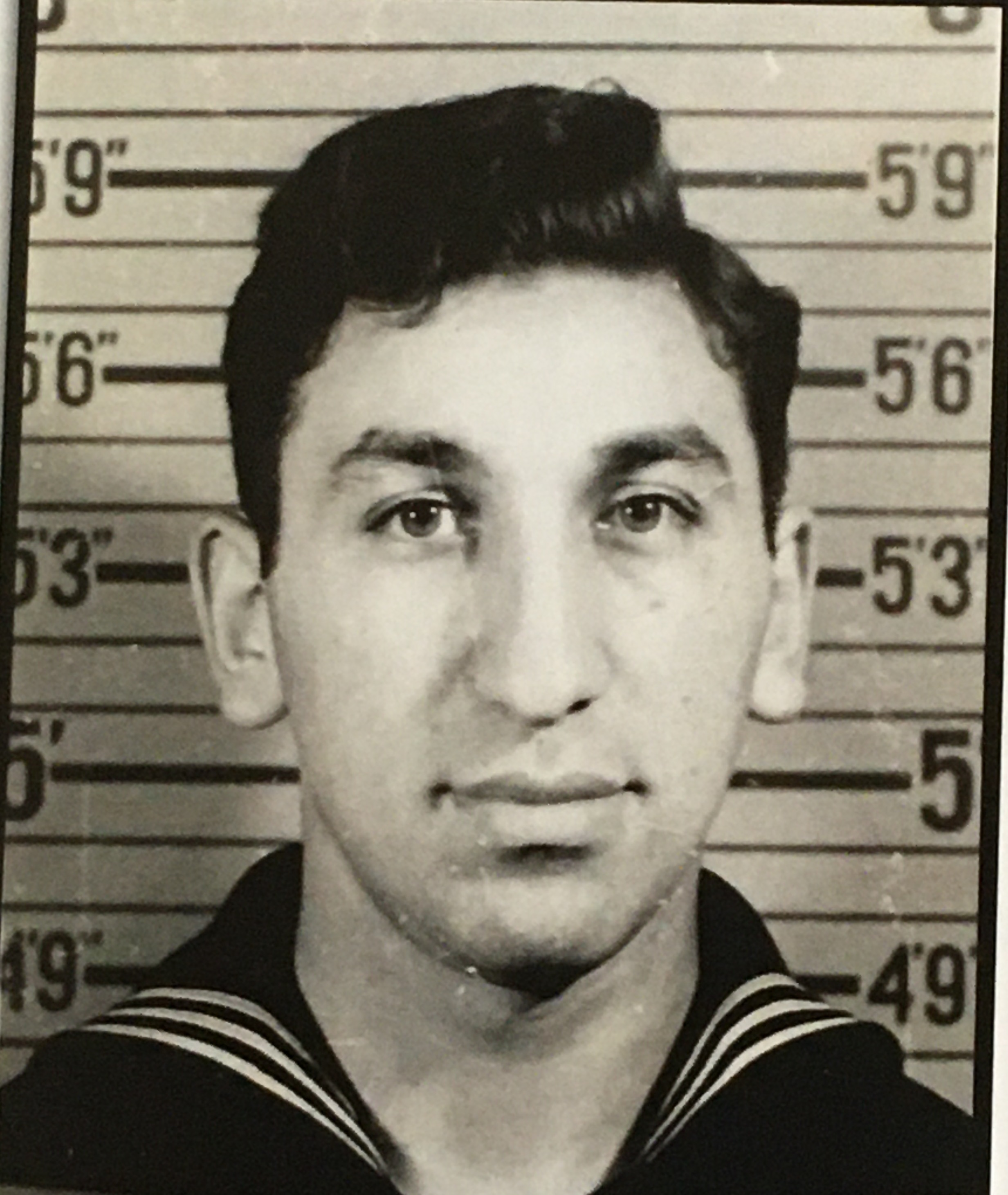

Seymour “Sy” Siegel was born in New York City in 1920 to a family of poor immigrants. His family fell apart when he was nine and he spent the rest of his childhood in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York with “a thousand brothers and sisters.” Life in the orphanage was harsh and highly regimented. When the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, he wanted to serve but was tired of being lost in the crowd and wanted a role where he had the opportunity to excel as an individual. The Coast Guard appealed to him and he enlisted in 1942.

Seymour “Sy” Siegel was born in New York City in 1920 to a family of poor immigrants. His family fell apart when he was nine and he spent the rest of his childhood in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York with “a thousand brothers and sisters.” Life in the orphanage was harsh and highly regimented. When the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, he wanted to serve but was tired of being lost in the crowd and wanted a role where he had the opportunity to excel as an individual. The Coast Guard appealed to him and he enlisted in 1942.

Siegel spent six weeks training at the Coast guard training center at Manhattan Beach, New York. There, he believed they spent most of their time fieldstripping firearms, but he also attended advanced specialty training to become a radioman. Soon, he realized however that he was not very technically inclined and trained instead as a radarman in Groton, Connecticut.

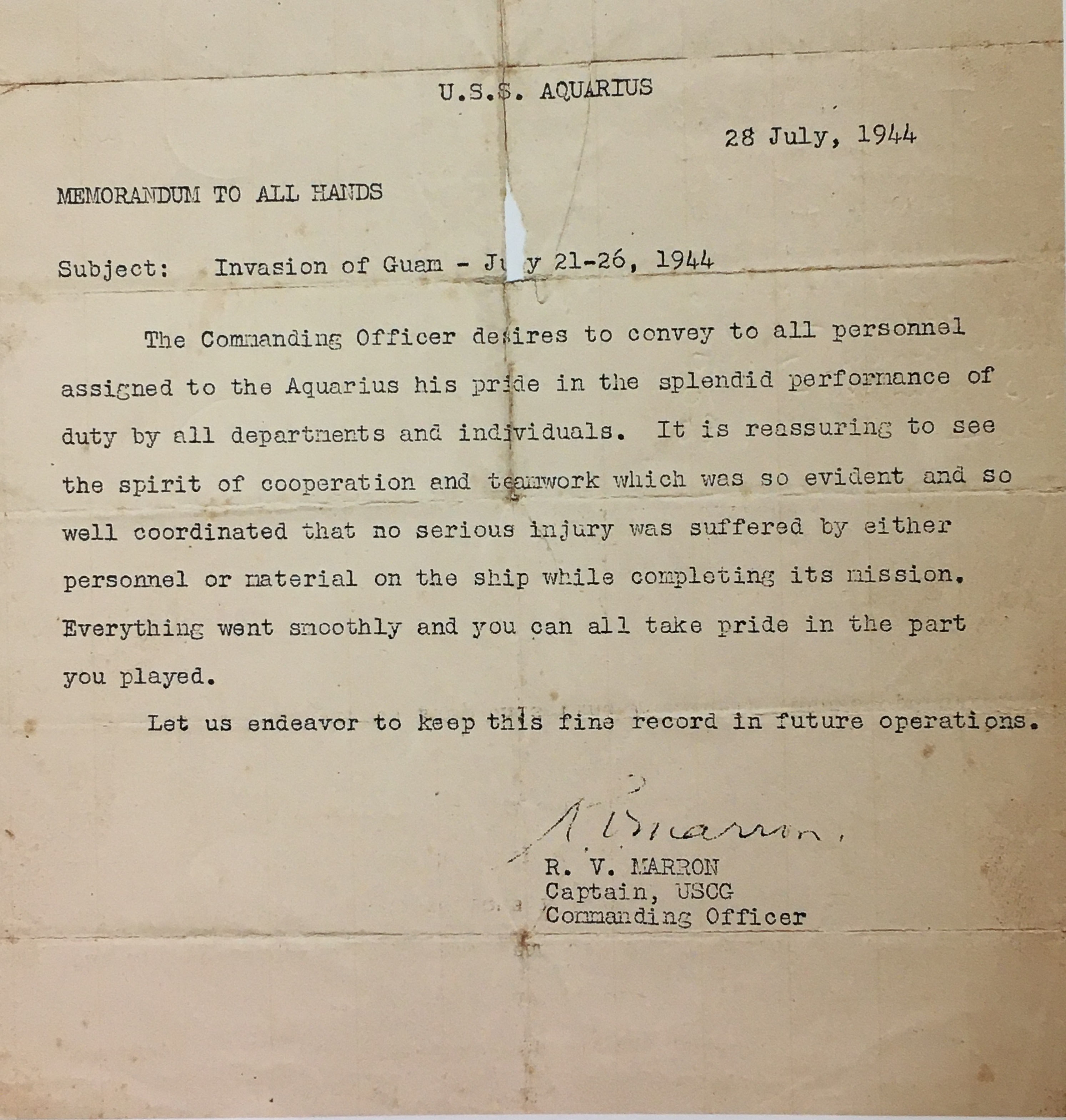

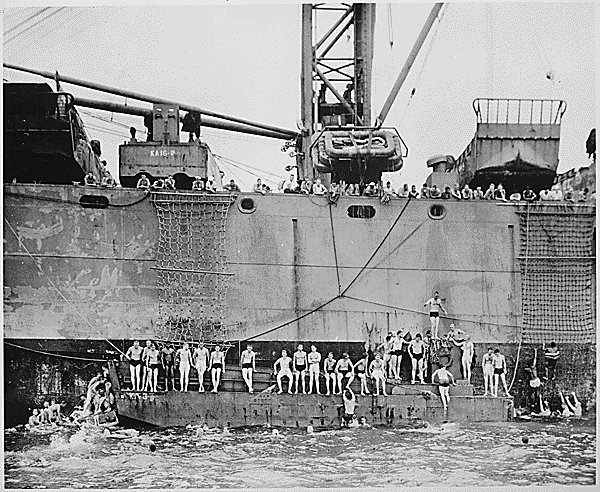

As a Jewish-American, Siegel felt a strong personal obligation to fight the Axis Powers and repeatedly requested assignment to a combat unit. In 1943, his request was granted and he received orders to the USS Aquarius, a 459-foot Coast Guard-crewed attack cargo ship whose mission was to carry landing craft, troops, and supplies for amphibious assaults. Upon arriving off a hostile landing area, the embarked Marines or Soldiers would climb down cargo nets into the lowered landing craft, which would disembark them on the beaches after they had been “softened up” by aircraft bombings and naval gunfire.

Aboard the Aquarius, Siegel’s battle station was the small radar shack where the ship’s radarmen would track friendly aircraft, watch for enemy ones, and help the ship navigate. During his 18 months aboard, he witnessed scenes that ranged from sublime tropical moonlit ocean nights to intense attacks by Japanese aircraft, “that looked like a Hollywood movie.” In all, he would participate in six amphibious assaults and kept a journal to document his experiences.

In 1944, during the bloody invasion of Peleliu, in Palau, casualties among the Marines were so high that the Aquarius had to serve as a makeshift hospital ship:

I am now receiving my first real impact of the effects of war on our troops . . . . Our casualties are lying in a [landing craft] alongside our ship. They are all shot up arms, legs, body, and shellshock victims. They lie inert, unconscious, one or two propped up against the bulkhead, another dead – a blanket thrown over him. Stretchers are being lowered by our boom. The process of raising them is a slow one due to lack of previous experience . . . . We are all a somber, sober group standing in a circle clear of the workers as we gaze at the cases brought aboard. They look bad. Bloodied grime, mud and dirt obscuring their features, eyes staring vacantly into space, lips twitching spasmodically. It is not a pretty sight – it is something you do not want to conjure up in your memory ever in the future . . . . The doctor and pharmacist are doing a Herculean job with the limited means at our disposal. We are not a hospital or evacuation ship and must do the best with what we have. (Note: Marines express gratitude for small amenities we Coast Guard crew provide in comparison to regular Navy Sailors.)

ship. They are all shot up arms, legs, body, and shellshock victims. They lie inert, unconscious, one or two propped up against the bulkhead, another dead – a blanket thrown over him. Stretchers are being lowered by our boom. The process of raising them is a slow one due to lack of previous experience . . . . We are all a somber, sober group standing in a circle clear of the workers as we gaze at the cases brought aboard. They look bad. Bloodied grime, mud and dirt obscuring their features, eyes staring vacantly into space, lips twitching spasmodically. It is not a pretty sight – it is something you do not want to conjure up in your memory ever in the future . . . . The doctor and pharmacist are doing a Herculean job with the limited means at our disposal. We are not a hospital or evacuation ship and must do the best with what we have. (Note: Marines express gratitude for small amenities we Coast Guard crew provide in comparison to regular Navy Sailors.)

Every few hours another boatload of badly mangled wounded pulls alongside for medical attention. We are already too seriously overcrowded and overworked to give the most successful treatment. These wounded have been refused at several other ships. Our doctor refuses to turn any injured away. He accepts them all and gives them the best care he can. He works with as many as 50 patients on an assembly line basis. The [chief’s mess] has been cleaned and transformed into a substitute operating room. Our doctor flies between this room and the dispensary, operating and giving first aid without rest. This is a tribute to his ability. Real genuine work - that of saving lives, not the treatment of heat rash, sniffles or athletes feet, vindicating any doubt as to his ability, we will not forget.

In 1945, during the liberation of the Philippines, the Aquarius came under repeated attack by Japanese aircraft:

It is 4 p.m., and the buzzer has gone off in a long, insistent dah-dah-dit, dah-dah-dit. This is G.Q. (General Quarters) and we all scamper for our stations. We’re receiving reports through the battle phone. “Gun to bridge – squadron of planes on starboard quarter – Bridge to all guns – be on the alert to identify airplanes before shooting in a dogfight. Gun A to Bridge – squadron of planes friendly. Gun 7 to control – anti-aircraft fire on port and starboard beam.” Again we sit closed-in, oblivious of what transpires on the outside. Then just as suddenly as it commenced, the all-clear sounded and we resumed normal duties. The score – no hits, no runs, no errors!

It was now dark, and with the night came a sense of relief and security, for the gloom offered the best defense against aircraft inasmuch as it made it difficult for a plane to see us. Several minutes later our illusion of security was shattered into tiny fragments. Firing, at first intermittent and haphazard, commenced. From the lead ship in  our column, the glowing tracers stretched 60-degree angles skyward; then quite rapidly other ships chimed in; the angle of fire was decreasing quickly until it was a crisscross fire and shells were almost hitting other ships opposite them. We were watching the engagement when, with lightning suddenness, there was a tremendous explosion, a wavy spurt of engulfing fire, followed by billowing clouds of smoke. A [Japanese] suicide pilot had crashed his plane onto the forward portion of the ship. Following on the heels of the catastrophe, we went to G.Q. stations as all ships momentarily slowed down . . . . From numerous reports, we gathered that many survivors were in the water. Various lookouts kept repeating: man in water on port bow – life raft with three men dead ahead – man shouting for help on port beam – more men 200 yards off starboard – one man, no life jacket on starboard bow . . . .

our column, the glowing tracers stretched 60-degree angles skyward; then quite rapidly other ships chimed in; the angle of fire was decreasing quickly until it was a crisscross fire and shells were almost hitting other ships opposite them. We were watching the engagement when, with lightning suddenness, there was a tremendous explosion, a wavy spurt of engulfing fire, followed by billowing clouds of smoke. A [Japanese] suicide pilot had crashed his plane onto the forward portion of the ship. Following on the heels of the catastrophe, we went to G.Q. stations as all ships momentarily slowed down . . . . From numerous reports, we gathered that many survivors were in the water. Various lookouts kept repeating: man in water on port bow – life raft with three men dead ahead – man shouting for help on port beam – more men 200 yards off starboard – one man, no life jacket on starboard bow . . . .

Threats were not limited to air attacks--mines, suicide boats, and kamikaze swimmers also threatened the Aquarius:

Reports over [the radio] urge lookouts to keep a sterner, more alert watch and to report all floating objects, including boxes that drift close by. [Japanese] have been discovered swimming out to ships with dynamite packs upon their backs acting as human torpedoes in suicide tactics, which have had little success thus far. Several have been killed with rifle fire in the water upon being sighted.

Following the Philippine Campaign, Siegel rotated back to the United States for “rest and rehabilitation.” After taking leave, he was assigned to the Coast Guard-manned destroyer escort USS Kirkpatrick, which had orders to proceed to the Pacific Theater. Siegel, however, still wanted to play an active role in the waning war against Nazi Germany. He again repeatedly volunteered for Coast Guard combat assignments in the European theatre, but ended the war installing radars on patrol craft at a shipyard in New York City. In  October 1945, he received an honorable discharge as a second class radarman.

October 1945, he received an honorable discharge as a second class radarman.

Today,. Siegel is 101 years old and resides in a rest home in New Jersey. He fondly recalls his time in the service:

The Coast Guard was an educational, rewarding, and life affirming experience. It reinforced my understanding of how a large organization functions. It broadened my understanding and appreciation of how different personalities as well as different military branches could work together towards a common goal. I made friendships there that I retained over the years and renewed at reunions. I learned the importance of rules, regulations, and discipline in organizations that provide services to others. It provided a framework for my role as an Executive Director of Jewish Family Services in Southern New Jersey.

Sy Siegel is one of many distinguished combat veterans of the long blue line.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to Ellen and Lisa Siegel for providing their father’s journal and photographs.]

Please click here for a PDF of Siegel's uniforms.