Nov. 19, 2021 —

[Prohibition] was a hard unremitting war with few of the rewards normally accompanying performance of such duty. Yet under the law, the Coast Guard had no alternative but to conduct it with zeal  and dedication, utilizing all the resources at its command. The story of the “Noble Experiment” is in large part a Coast Guard story.

and dedication, utilizing all the resources at its command. The story of the “Noble Experiment” is in large part a Coast Guard story.

Commandant Edwin J. Roland, United States Coast Guard

In October 1919, over 10 0 years ago, Congress passed the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and, in 1920, the Volstead Act, which enforced the 18th Amendment. And so began the so-called “Noble Experiment” of Prohibition. In America’s territorial waters, including its lakes, inland waterways and thousands of miles of coastline, the U.S. Coast Guard was the lone enforcer of this unpopular law.

0 years ago, Congress passed the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and, in 1920, the Volstead Act, which enforced the 18th Amendment. And so began the so-called “Noble Experiment” of Prohibition. In America’s territorial waters, including its lakes, inland waterways and thousands of miles of coastline, the U.S. Coast Guard was the lone enforcer of this unpopular law.

Enforcing the law under Prohibition would become the largest law enforcement mission in the long and storied history of the Coast Guard. By 1922, the Federal Prohibition Commission counted hundreds of mother ships hovering off U.S. shores in “Rum Row” with up to 60 off the Jersey Coast alone. These mother ships were also stationed off of Boston, New York, the Chesapeake Bay, New Orleans and West Coast ports. By 1923, Coast Guard Commandant William Reynolds admitted his cutters could prevent “only a small part” of the onrush of illegal booze, which was “entirely unprecedented in the history of the country.”

At that time, Congress had not appropriated any funds to the Coast Guard to stem the tide of these smugglers rum runners. However, expansion of the service happened quickly. By October 1923, Reynolds submitted a plan to Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon to deal with the situation. Reynolds called for 20 new high-seas cutters, 200 coastal patrol cutters and 90 fast picket boats. He asked for $20 million in supplemental funding for this vast fleet and 3,500 additional personnel to crew it – at the time, it was an incredible request for funds.

Based on Reynolds’ figures, Se cretary Mellon recommended enlarging the Coast Guard at a cost of $28.5 million, over three times the service’s 1923 annual budget. Congress agreed to Mellon’s proposal, but appropriated only half the amount or about $13 million with most of the funds going to fleet expansion and increased manpower. Up to that time, it was the largest funding increase in Coast Guard history.

cretary Mellon recommended enlarging the Coast Guard at a cost of $28.5 million, over three times the service’s 1923 annual budget. Congress agreed to Mellon’s proposal, but appropriated only half the amount or about $13 million with most of the funds going to fleet expansion and increased manpower. Up to that time, it was the largest funding increase in Coast Guard history.

New Coast Guard appropriations focused on rapid expansion and, by 1924, the funds began to flow. New high-seas cutters that Reynolds requested were shelved in favor of 20 mothball ed U.S. Navy destroyers that could be refurbished quicker than new construction. Personnel increases, new boats, and refurbished destroyers quickly burned through the $13 million supplemental funding.

ed U.S. Navy destroyers that could be refurbished quicker than new construction. Personnel increases, new boats, and refurbished destroyers quickly burned through the $13 million supplemental funding.

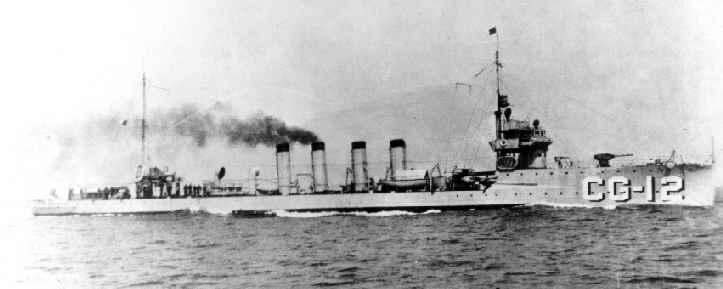

Seven hundred fifty-ton and 1,000-to destroyers that were built between 1910 and 1916 were transferred to the Coast Guard. Later, some of the Navy’s famed “Four-Stacker” destroyers were also transf erred. Lots of repair work was required with one destroyer described by its Coast Guard captain as an “appalling mass of junk.” The first refurbished destroyer, Henley, went to sea in summer of 1924. The majority of its Coast Guard crew were raw recruits. These destroyers were the first Navy warships manned entirely by Coast Guard crews.

erred. Lots of repair work was required with one destroyer described by its Coast Guard captain as an “appalling mass of junk.” The first refurbished destroyer, Henley, went to sea in summer of 1924. The majority of its Coast Guard crew were raw recruits. These destroyers were the first Navy warships manned entirely by Coast Guard crews.

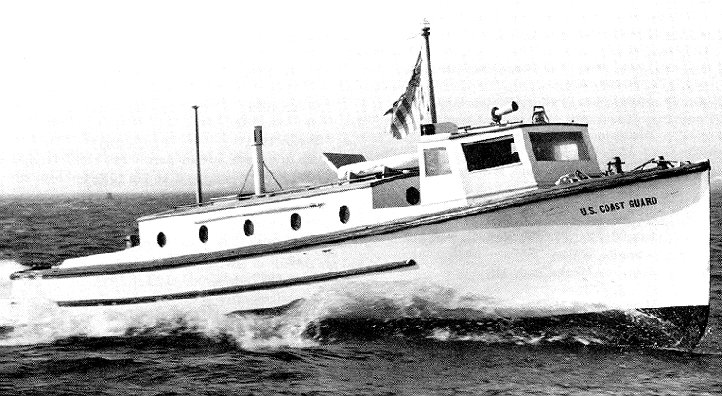

In 1924, the Coast Guard’s small boat fleet also mushroomed. The service re-purposed over 450 seized rum-running boats for pursuit and apprehension purposes. In addition, a fleet of 103 36-foot Picket Boats were built for fast inshore work. Thirty of these were stripped down for a top speed of 22 knots while the rest had double-cabins for overnight patrols and were two knots slower. Later, between 1931 and 1932, another 550 38-foot picket boats were built to replace the 36-footers. At 24 knots, they were faster than their predecessors with more enclosed space for longer patrols. To help support this massive small-boat fleet, the Coast Guard acquired six floating bases placing them in strategic locations along the East Coast.

During Prohibition, the service also experienced a dramatic increase in its new cutter inventory. With over 200 cutters, the wooden 75-foot “Six Bitter” class was the largest cutter class in Coast Guard his tory. With a speed of 15 knots, its mission was offshore picket duty. Most Six-Bitters were operational by 1925

tory. With a speed of 15 knots, its mission was offshore picket duty. Most Six-Bitters were operational by 1925 accounting for half the personnel increases at that time. The service built 13 100-footers out of steel, rather than wood. The larger size provided greater crew comfort and added endurance, but they lacked the speed of the Six-Bitters. The service also built six 78-foot patrol boats, a faster version of the Six-Bitter that could speed at 22 knots. Known as “Buck-and-a-Quarters,” 33 125-foot cutters were built in the late 1920s. Their diesel engines ensured reliability and endurance, but a top speed of only ten knots. Designed to track mother ships, the successful 165-foot “B” class cutters maximized speed, seaworthiness, accommodations and range. Eighteen “B” class cutters were completed before the end of Prohibition. Commissioned in the late 1920s, 10 250-foot “Lake” class cutters were high-endurance ships that could serve long periods at sea.

accounting for half the personnel increases at that time. The service built 13 100-footers out of steel, rather than wood. The larger size provided greater crew comfort and added endurance, but they lacked the speed of the Six-Bitters. The service also built six 78-foot patrol boats, a faster version of the Six-Bitter that could speed at 22 knots. Known as “Buck-and-a-Quarters,” 33 125-foot cutters were built in the late 1920s. Their diesel engines ensured reliability and endurance, but a top speed of only ten knots. Designed to track mother ships, the successful 165-foot “B” class cutters maximized speed, seaworthiness, accommodations and range. Eighteen “B” class cutters were completed before the end of Prohibition. Commissioned in the late 1920s, 10 250-foot “Lake” class cutters were high-endurance ships that could serve long periods at sea.

Despite the state of flying during this wood, wire, and propeller age, the potential of aviation to interdict smugglers was not lost on Coast Guard officers. In 1920, the service tried to establish a Coast Guard air arm with loaned Navy aircraft and a former Navy airfield in Morehead City, N.C. A year later, lack of funds killed the program. However, a year later, Coast Guard officers convinced service leadership that aerial patrols could observe far more of the water’s surface than cutters. And so began the permanent establishment of Coast Guard aviation.

In May 1925, temporary Coast Guard operations were set-up at Squantum Naval Air Station in Massachusetts. The service’s first aerial law enforcement assist took place June 20 and the first Coast Guard aviation interdiction took place four days later on the 24th. A year later, in recognition of aviation’s importance, Congress funded the purchase of five new Coast Guard aircraft, the first of thousands of service air assets. These custom-built Loening OL-5 amphibians had a top speed of 150 miles per hour and a range of 450 miles. The Coast Guard provided each one with a  radio and aft-mounted machine gun to increase their effectiveness. The first amphibian OL-5s were based at a small air station on Ten Pound Island in Gloucester Harbor, Mass.

radio and aft-mounted machine gun to increase their effectiveness. The first amphibian OL-5s were based at a small air station on Ten Pound Island in Gloucester Harbor, Mass.

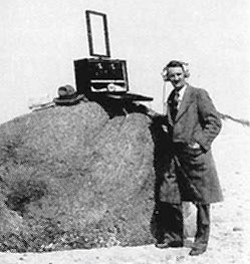

In the early 20th century, development of the radio had brought new ways to communicate and new ways to locate radio transmissions both at sea and on shore. As early as 1919, the radio direction finder (RDF) had come into use in a primitive form on the cutter Androscoggin. Two years later, a Navy version was installed on the cutter Tampa and others soon followed. During Prohibition, these devices aided in detecting lines of bearing on transmissions from mother ships, rum-running boats and their clandestine shore transmission stations. Two cutters working together could establish fixes on the illegal transmitters. On the other hand, smugglers also became more sophisticated and used RDF to locate Coast Guard units as well. It was a huge game of cat and mouse off U.S. shores, and on American lakes and inland waterways.

As early as 1919, the radio direction finder (RDF) had come into use in a primitive form on the cutter Androscoggin. Two years later, a Navy version was installed on the cutter Tampa and others soon followed. During Prohibition, these devices aided in detecting lines of bearing on transmissions from mother ships, rum-running boats and their clandestine shore transmission stations. Two cutters working together could establish fixes on the illegal transmitters. On the other hand, smugglers also became more sophisticated and used RDF to locate Coast Guard units as well. It was a huge game of cat and mouse off U.S. shores, and on American lakes and inland waterways.

During Prohibition, the Coast Guard’s largest law enforcement mission, the service experienced the largest peacetime fleet expansion in its history. With 320 cutters and destroyers, and hundreds of smaller boats, the service’s budget mushroomed from $9.3 million in 1923 to over $24 million in 1927 with personnel levels more than doubling from 4,000 men to 10,000. And, the service saw many firsts, including the first time Coast Guard crews manned Navy warships and the permanent establishment of a Coast Guard aviation branch. It also saw extensive use of the radio and RDF. All of these factors shaped the service into a force better prepared for its next great challenge—World War II.