June 24, 2021 —

Chief Warrant Officer R. David Lewald and the crew of Pamlico can be justly proud of the significant role they played in this most challenging operation. There are many people alive today because of their highly skilled efforts.

~ retired Rear Adm. Robert F. Duncan, U.S. Coast Guard

On Aug. 28, 2005, the C oast Guard’s 160-foot construction tender Pamlico (WLIC-800) was spudded down on the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Under the command of Chief Warrant Officer R. David Lewald, the Pamlico was command ship for a flotilla of Coast Guard vessels that had evacuated up the Mississippi to ride out Hurricane Katrina. This fleet of watercraft included eight 41-foot utility boats, three 55-foot aids-to-navigation boats and the construction tender Clamp.

oast Guard’s 160-foot construction tender Pamlico (WLIC-800) was spudded down on the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Under the command of Chief Warrant Officer R. David Lewald, the Pamlico was command ship for a flotilla of Coast Guard vessels that had evacuated up the Mississippi to ride out Hurricane Katrina. This fleet of watercraft included eight 41-foot utility boats, three 55-foot aids-to-navigation boats and the construction tender Clamp.

While they sheltered in Baton Rouge, Katrina battered the Coast Guard craft with heavy rain and 55-knot sustained winds that grew stronger by the hour. However, the vessels all escaped damage and the storm passed over them by evening. Lewald planned to return to New Orleans in the morning. He consulted with the Coast Guard Emergency Command Center in Baton Rouge, where Lt. Cmdr. Gregory Purvis directed him to, “Head down the river and see what you can do.”

While they sheltered in Baton Rouge, Katrina battered the Coast Guard craft with heavy rain and 55-knot sustained winds that grew stronger by the hour. However, the vessels all escaped damage and the storm passed over them by evening. Lewald planned to return to New Orleans in the morning. He consulted with the Coast Guard Emergency Command Center in Baton Rouge, where Lt. Cmdr. Gregory Purvis directed him to, “Head down the river and see what you can do.”

It is around 130 winding Mississippi River miles from Baton Rouge to New Orleans. Pamlico its flotilla downriver, including the 41-foot utility boats from stations New Orleans, Venice, Louisiana, and Gulfport, Mississippi, the 55-foot aids-to-navigation boats from the Aids-to-Navigation Teams and the Coast Guard Cutter Clamp. As yet, they had no information on conditions in New Orleans, but the crews witnessed increased devastation as they proceeded south. Masses of trees were blown down and boats and barges were left high and dry on the river banks. Averaging 10 knots, the flotilla arrived on the outskirts of New Orleans at dusk on the 29th.

The damage to downtown New Orleans appeared to be moderate. Windows had been blown out of high-rise buildings and fires spread smoke skyward. However, few realized that the levees protecting large parts of the city had been breached by storm surge, were structurally failing, or were otherwise damaged. Much of New Orleans lies below sea level, so the flooding intensified, especially east of the Industrial Canal on the East Bank of the Mississippi.

The damage to downtown New Orleans appeared to be moderate. Windows had been blown out of high-rise buildings and fires spread smoke skyward. However, few realized that the levees protecting large parts of the city had been breached by storm surge, were structurally failing, or were otherwise damaged. Much of New Orleans lies below sea level, so the flooding intensified, especially east of the Industrial Canal on the East Bank of the Mississippi.

The Navy’s Naval Support Activity facility located on the East Bank radioed Lewald requesting assistance with a crowd of residents seeking refuge. Lewald directed his smallboats to pick up the evacuees and drop them off in Algiers, Louisiana on the West Bank. After completing that mission, Lewald’s first instinct was to moor at the Naval Support Activity, but the commanding officer refused his request. Instead, the Pamlico moored at the Algiers Ferry Terminal across from downtown New Orleans.

After sunset on Aug. 30th, the city was completely dark. The weather was still and hot, even at night, and Coast Guardsmen paced uneasily in the buggy humid air. Like the other Coasties in the area, they were concerned about the safety of their homes and families. A large explosion at a facility across the river in the early hours of the morning set nerves on edge even further.

On the 31st, the rising sun was hot and brought more bad news: St. Bernard Parish, to the south, had been hit even worse than the city. As Coast Gu ard boats from Venice, New Orleans, and Gulfport fanned out and began picking up victims along the city’s waterfront, the Pamlico got a radio call from a local tugboat, the Blackbeard. Hundreds of victims were accumulating downriver in Chalmette, where displaced people had evacuated themselves or been deposited after being rescued by agencies like the local sheriff’s department. The Blackbeard was willing to ferry them across the river on its barge, which could carry 500 people at a time. Should they begin ferrying? Lewald concurred and directed Coast Guard boats to escort.

ard boats from Venice, New Orleans, and Gulfport fanned out and began picking up victims along the city’s waterfront, the Pamlico got a radio call from a local tugboat, the Blackbeard. Hundreds of victims were accumulating downriver in Chalmette, where displaced people had evacuated themselves or been deposited after being rescued by agencies like the local sheriff’s department. The Blackbeard was willing to ferry them across the river on its barge, which could carry 500 people at a time. Should they begin ferrying? Lewald concurred and directed Coast Guard boats to escort.

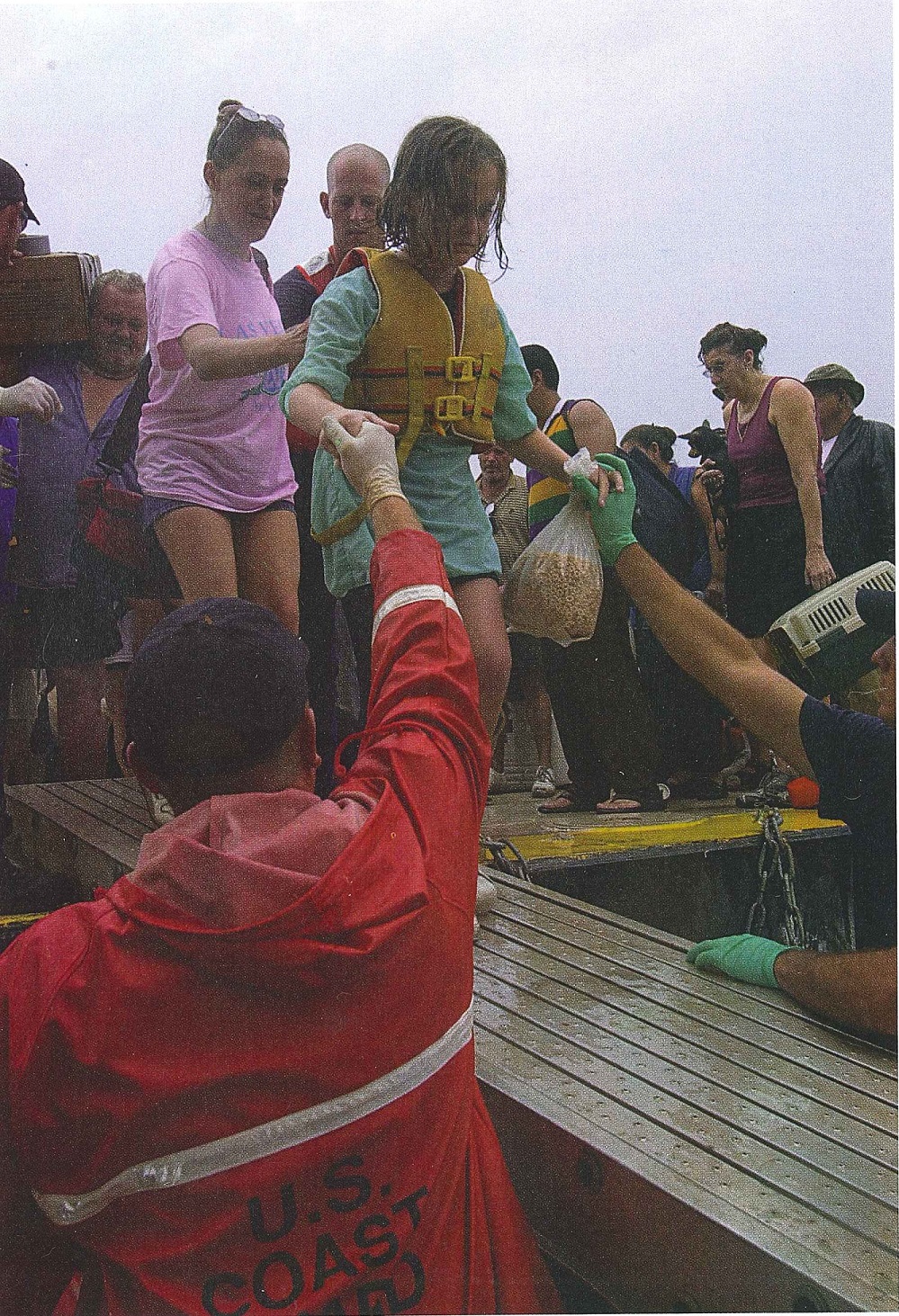

The evacuation of several thousand people was now the responsibility of a Coast Guard chief warrant officer operating entirely on his own initiative. Lewald described the scene as, “the Wild West at Dunkirk.” The Blackbeard and other local tugs began transporting hundreds of victims to the Pamlico’s mooring at the Algiers Ferry Terminal. Evacuees arriving by barge and Coast Guard boats were triaged with the ill or injured flown out by Coast Guard helicopters from an improvised landing zone next to the terminal. Later, larger helicopters including U.S. Army “Chinooks,” would evacuate casualties. Most other victims were bussed out through the non-flooded West Bank with police escort. Many victims had lost everything in the storm and were hot, thirsty, hungry, and frustrated. Tensions ran high.

Contrary to popular belief, the Coast Guard’s response to Katrina was not simply wild improvisation. The District 8 commander, Rear Adm. Robert Duncan, had gained significant hurricane response experience during Hurricanes Hugo and Bob, and had thoroughly planned and trained for a catastrophic weather scenario. District 8 had prepared extensively, even re-purposing the disestablished District 2 command center in St. Louis. Coast Guardsmen in the field relied heavily on District 8’s plans and preparations, along with the admiral’s Commander’s Intent and Concept of Operations. These instructions could be summarized as “don’t wait for permission,” and they became the basis for successful improvisation.

Back aboard the Coast Guard flotilla that became known as the “Algiers Point Armada,” the spirit of initiative extended from Lewald down to the  most junior enlisted personnel. One Coastie salvaged hundreds of lifejackets from wrecked ferries for victims being transported on the barges. And, evacuees could not be frisked before reaching the terminal. So, newly reported Pamlico Fireman Joshua Nguyen invented “amnesty boxes”

most junior enlisted personnel. One Coastie salvaged hundreds of lifejackets from wrecked ferries for victims being transported on the barges. And, evacuees could not be frisked before reaching the terminal. So, newly reported Pamlico Fireman Joshua Nguyen invented “amnesty boxes”  in which victims could surrender contraband. Over 500 firearms were surrendered, which the Coasties kept in hopes they could be forensically analyzed. However, the prodigious number of knives, drugs and alcohol had to be dumped.

in which victims could surrender contraband. Over 500 firearms were surrendered, which the Coasties kept in hopes they could be forensically analyzed. However, the prodigious number of knives, drugs and alcohol had to be dumped.

Lewald’s communications with higher command, or even supervisors at Sector New Orleans, were non-existent, but he did meet with the St. Bernard Parish Sheriff to firm up an evacuation plan. Lewald’s only non-line-of-sight communication was the high-frequency radio on the Pamlico, but the only unit it could reach was Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, in North Carolina, whose puzzled watch-stander had to re-transmit messages for Pamlico. Luckily, Lewald later appropriated a satellite phone from a Coast Guard Disaster Assistance Response Team member.

Over the next few days, the security situation deteriorated. The amount of gunfire in the city increased, as did the number of victims appearing at the terminal with gunshot wounds. One night, the Coasties watched muzzle flashes flare back and forth from a firefight across the river. During the day, people d rove up in stolen police cars and tried to lure Coasties away from the terminal. Meanwhile, Coast Guard personnel and boats from Louisiana and around the country began to arrive. One night, Lewald greeted a crew who arrived after a 4-hour trip downriver on a fireboat with the warning: “Welcome to the Pamlico, we own the day and do not own the night. Stay on your boats and do not go on land at night. Anyone who tries to board our boats or cutter are not our friends. If anyone tries to board, they are here to harm us.”

rove up in stolen police cars and tried to lure Coasties away from the terminal. Meanwhile, Coast Guard personnel and boats from Louisiana and around the country began to arrive. One night, Lewald greeted a crew who arrived after a 4-hour trip downriver on a fireboat with the warning: “Welcome to the Pamlico, we own the day and do not own the night. Stay on your boats and do not go on land at night. Anyone who tries to board our boats or cutter are not our friends. If anyone tries to board, they are here to harm us.”

The Pamlico did not typically carry firearms for its ATON crew. However, Stations Venice and Gulfport took their armories with them when they evacuated and deposited excess firearms on board the tender. Fortunately, it did not prove necessary to arm Pamlico’s crew. Members from the local Coast Guard Maritime Safety and Security Team (MSST) arrived and brought welcome protection--one of the team was even assigned as a Lewald’s bodyguard while he interacted with storm evacuees.

Eventually, the Algiers Ferry Terminal developed into a Coast Guard forward operating base. Nightly, the Pamlico would withdraw and spud down in the riverbed with the smallboats tied up alongside. The crews tried to catch sleep on their boats despite the heat and virulent mosquitoes. During the day, the Algiers Point Armada returned to the dock and Coasties armed with M16 rifles cleared the area around it to form a defensive perimeter.

The situation deteriorated as filthy and polluted floodwaters rose. With little verifiable information reaching the crews, rumors flew. A truck full of hotdogs arrived from a church in the Midwest driven by a man in a police uniform armed with a shotgun. When asked, he admitted he had borrowed the uniform because he thought people would be less likely to harass him. The Coasties secured the shotgun and distributed his hotdogs.

Despite the danger, the operational tempo increased. At its daytime peak, the Coast Guard was evacuating 750 people per hour by boat and 100 by air. As time went on, the condition of arriving victims grew worse, including diabetics, the elderly, and those with pre-existing conditions. By bartering diesel, the crew ensured local ambulance support. On one day, a local nurse nam ed Cindy Fourman volunteered to help triage victims. At sunrise, Nurse Fourman covertly accessed the terminal and then snuck home at sunset without an escort after helping save over 250 lives.

ed Cindy Fourman volunteered to help triage victims. At sunrise, Nurse Fourman covertly accessed the terminal and then snuck home at sunset without an escort after helping save over 250 lives.

On Sept. 1st, the Algiers evacuation effort safely transported 1,200 evacuees but could move no more people due to lack of buses on the West Bank. Coast Guard Cutter Clamp’s officer-in-charge, Master Chief Petty Officer Warren Woodell, ordered his executive petty officer, Petty Officer 1st Class Thomas Faulkenberry, and Seaman Justin Witt to improvise alternative transportation. With the help of some New Orleans police officers and local sheriffs’ deputies, they commandeered abandoned city and school buses to evacuate over 100 evacuees inland.

On that same day, the Coast Guard’s medium-endurance Cutter Spencer (WMEC-905) arrived off downtown New Orleans. After Lewald warned the cutter against mooring at the unsecured Riverwalk, it dropped anchor in the river. Lewald went aboard to brief the command. At the time, he had not showered in days and was bleeding from a neck wound from a flying rock caused by a Chinook liftoff. Unaccustomed to air conditioning, he began shivering when he met the commanding officer inside the cutter. Together they devised a plan for Spencer to assume control of the Algiers Point relief operations.

The arrival of Spencer dramatically improved communications and operations. The cutter’s crew provided security and humanitarian assistance, while its officers assessed the situation in downtown New Orleans. Spencer’s capabilities enabled the Algiers Ferry Terminal-based Coasties to shower and get welcome sleep aboard a climate-controlled cutter. Communications and coordination also increased with operating bases at Zephyr Field and Station New Orleans on Lake Pontchartrain. Meanwhile, evacuating victims continued as Coast Guard and other agency aircraft, vessels, and personnel arrived, including Air Force Pararescue personnel, National Guardsmen drawn from across the U.S., and soldiers from the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division.

On Sept. 4th, with the arrival of the Navy’s amphibious assault ship USS Tortuga, the mission of the Pamlico and the Algiers Point Armada finally ended. Having coordinated and supported the evacuation of several thousand people from a damaged city in which law and order had broken down, the Pamlico could now shift focus to its normal mission: aids to navigation. On Sept. 5th, the tender pushed off the bank and headed downriver bound for Venice at the mouth of the Mississippi. At the time, the crew did not realize that Pamlico’s Katrina response operations would draw global acclaim, but they did know that their work was far from over.

Please click here for part two...