July 9, 2021 —

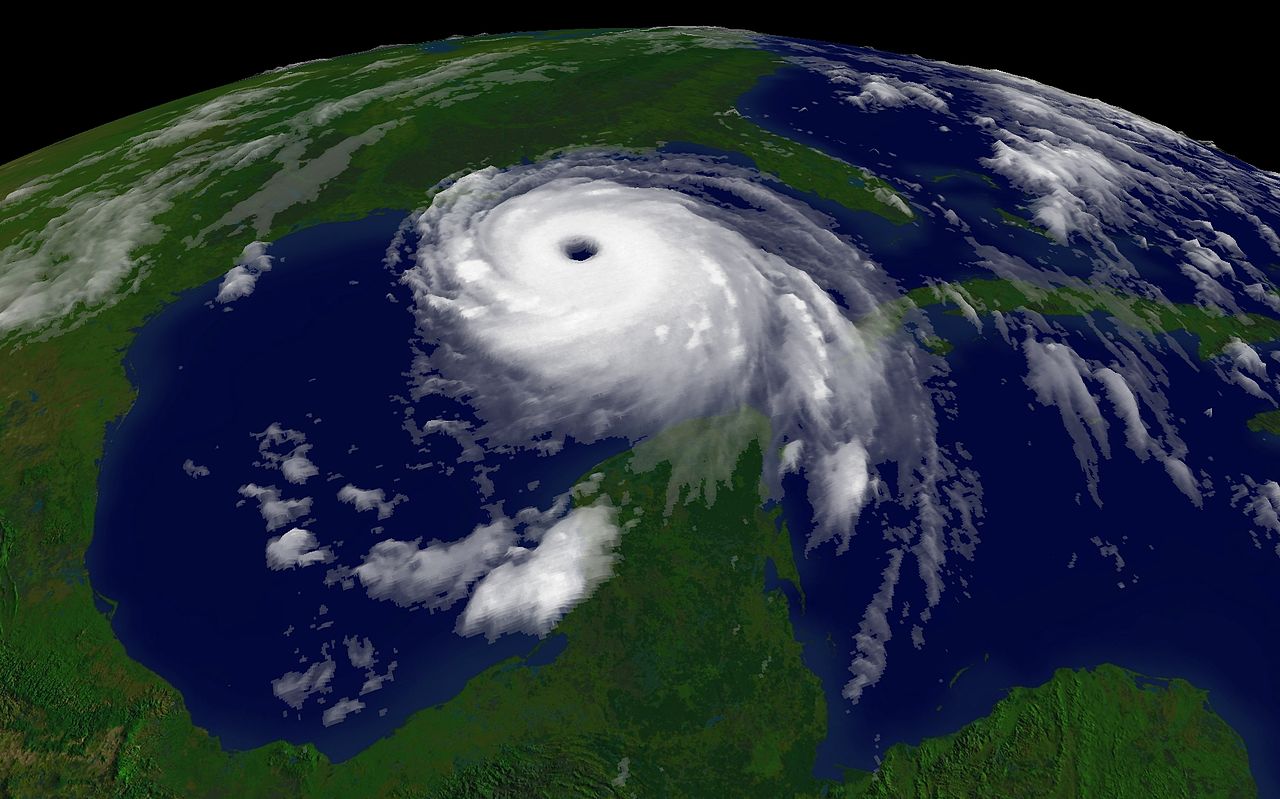

Hurricane Katrina earned the title as one of the deadliest natural disasters to strike North America. The superstorm displaced over 600,000 households, took the lives of over 1,800 people, and is currently tied with Hurricane Harvey as causing the largest amount of damage, estimated around $125 billion.

In 2005, the Category 3 hurricane made landfall between Grand Isle, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, bringing with it winds up to 125 mph and storm surges up to 27 feet above sea level. The average elevation for the city of New Orleans is six feet below sea level, however, so the storm caused severe flooding for over 80% of the city.

In 2005, the Category 3 hurricane made landfall between Grand Isle, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, bringing with it winds up to 125 mph and storm surges up to 27 feet above sea level. The average elevation for the city of New Orleans is six feet below sea level, however, so the storm caused severe flooding for over 80% of the city.

In true Coast Guard fashion of Semper Paratus (“Always Ready”) the service planned for the incoming hurricane and pre-staged air assets in Texas, Florida, and North Carolina. Regardless of their duty station, Coast Guard men and women from all over were itching to join the response effort, including Cmdr. James O’Keefe.

James “Jim” O’Keefe w as commissioned in the Navy in 1983 and started his career as a Navy aviator. In 1991, he decided to switch to the Coast Guard through the direct commission aviator program. One of the things that O’Keefe loved about the Coast Guard’s aviation program was “in the Navy probably 90% of my stuff was training while in the Coast Guard 70% was actually going out there and doing something.” O’Keefe also loved the Coast Guard mission of helping Americans earning his first Distinguished Flying Cross Medal (DFC) in 1999, during a search and rescue mission off the coast of Sitka, Alaska.

as commissioned in the Navy in 1983 and started his career as a Navy aviator. In 1991, he decided to switch to the Coast Guard through the direct commission aviator program. One of the things that O’Keefe loved about the Coast Guard’s aviation program was “in the Navy probably 90% of my stuff was training while in the Coast Guard 70% was actually going out there and doing something.” O’Keefe also loved the Coast Guard mission of helping Americans earning his first Distinguished Flying Cross Medal (DFC) in 1999, during a search and rescue mission off the coast of Sitka, Alaska.

When Hurricane Katrina hit on Aug. 29, 2005, O’Keefe was stationed at the Aviation Training Center in Mobile, Alabama. O’Keefe recounted that at the training center aviators did very little operational work. They flew occasional search and rescue missions, if other aviation crews were unavailable, and responded to hurricanes every season, but for the most part the routine was pretty standardized.

“Katrina, at first, seemed to be just another hurricane coming in,” O’Keefe said. “We figured we’d have some sort of response, but that weekend my family went to Panama City for my daughter’s soccer tournament. I thought I would do whatever was needed to respond to Katrina when I came back.”

However, when Katrina entered the Gulf, the hurricane boasted Category 5 strength, and O’Keefe knew he would be needed sooner than anticipated.

“The soccer tournament actually ended up getting cancelled and we drove through part of the hurricane coming back from Panama City to Alabama.” O’Keefe recalled “I just wanted to get back and get in a plane and help out.”

recalled “I just wanted to get back and get in a plane and help out.”

When O’Keefe returned to base, there were no helicopters left for him to fly. “By the time I actually got a crew and an aircraft, it was probably 30 hours after the first launch.”

Before O’Keefe took to the air, the only instructions from his commanding officer, Capt. Dave Callahan, were “Go to New Orleans and do whatever you can to help!” That is exactly what he and his aircrew did.

In his effort to help after Katrina, O’Keefe flew 29 hours of helicopter rescue, evacuation and transportation missions in the area of operation.

“The destruction was devastating,” he remembered. “Everywhere you went there was someone who needed our help.”

O’Keefe’s first two missions when he reported were transportation operations. “My first mission was to transport a rather large lady to Baton Rouge hospital which was about 70 to 80 miles away. Right after that we had to do another one where we actually ended up landing between two sets of power lines to pick this guy up from an ambulance.”

During his deployment, O’Keefe and his aircrew performed missions, such as rescuing victims from their roofs, evacuating a hospital in the late hours of the night, and operating in areas where there was a report of gunfire.

“We took about three missions where there were reports of helicopters being shot at, and would we accept it, and I was flying an unarmed helicopter with no armor. I never refused a mission because someone was  possibly shooting at us; we took every opportunity we could to help people.”

possibly shooting at us; we took every opportunity we could to help people.”

Nothing fazed O’Keefe. “We were a little out of our element. We never really trained to fly around buildings,” but he was committed to the Coast Guard core value of devotion to duty.

During Katrina flight operations, O’Keefe successfully rescued 214 storm victims, earning him his second Distinguished Flying Cross medal. “Earning the DFC was nice, but what really mattered was I actually got to do my job. I was going out there and saving people on probably the worst day of their life.”

In July 2016, Jim O’Keefe retired from the Coast Guard as a captain. He currently resides with his family in Northern Virginia and is working on a memoir of his time in the military, titled “Talk Cool, Fly Cool, and Other Stories.”