April 9, 2021 —

In early April 1917, the United States entered World War I, the U.S. Navy communications center in Arlington, Virginia, t

In early April 1917, the United States entered World War I, the U.S. Navy communications center in Arlington, Virginia, t ransmitted the code words “Plan One, Acknowledge” to Coast Guard cutters, units, and bases throughout the U.S. This coded message initiated the service’s transfer from the Treasury Department to the Navy placing the U.S. Coast Guard on a wartime footing.

ransmitted the code words “Plan One, Acknowledge” to Coast Guard cutters, units, and bases throughout the U.S. This coded message initiated the service’s transfer from the Treasury Department to the Navy placing the U.S. Coast Guard on a wartime footing.

“Plan One” was developed in secret, laying out the transfer of the Coast Guard to the Navy. In March 1917, in anticipation of the declaration of war, Commandant Bertholf had issued a confidential booklet that laid out Plan One and the assignments of cutters to various Naval Districts. When the U.S. declared war against Germany on Friday, April 6th, Bertholf authorized transmission of Plan One in an “ALCUT” (all cutters) message, a coded dispatch transmitted by radio and telegraph, to every cutter and shore station in the Coast Guard.

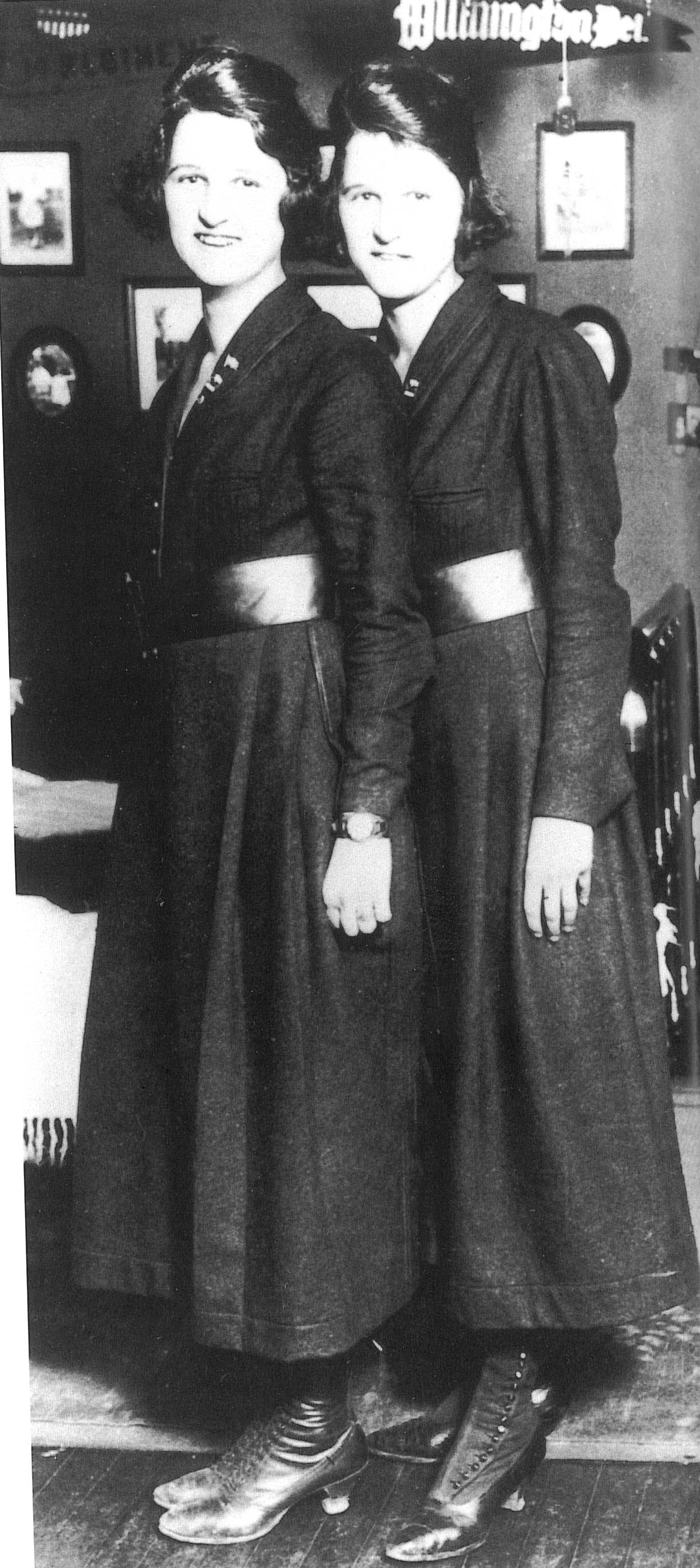

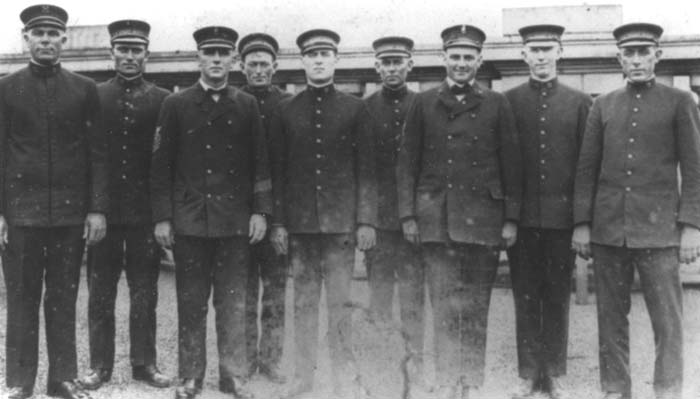

With the declaration of war and “Plan One” dispatch, the Coast Guard had joined the fight. The Treasury Department transferred officers and enlisted men, cutters, and units to the operational control of the Navy Department. The service augmented the Navy with 223 commissioned officers and 4,500 enlisted personnel. The latter number included the first women to don Coast Guard uniforms and the first significant number of minority Coast Guardsmen to serve.

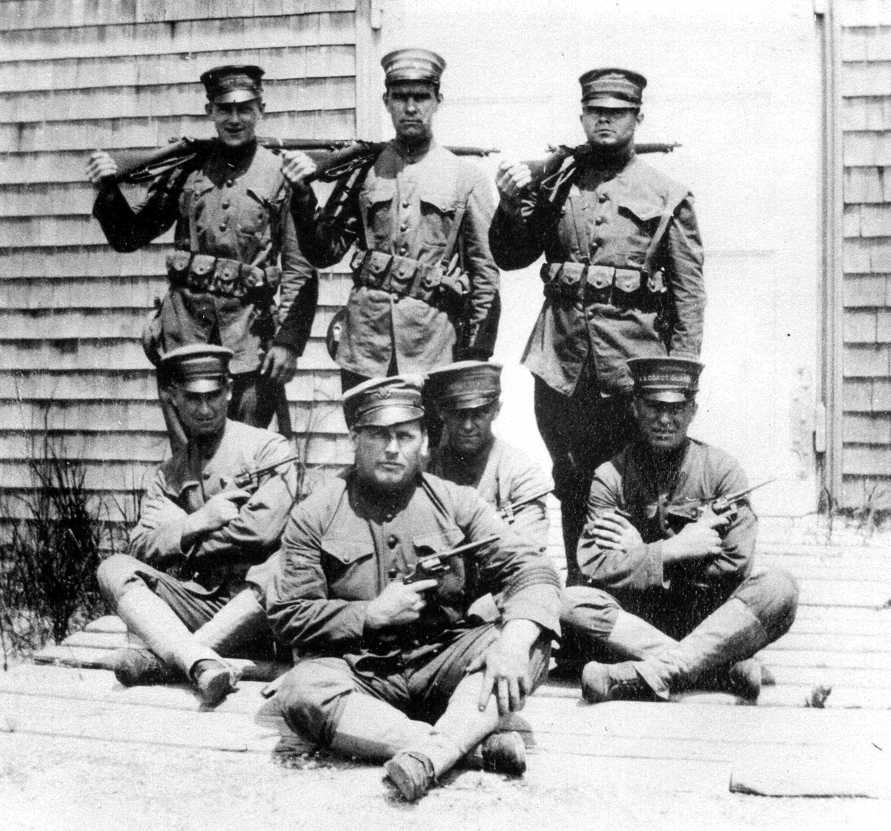

One of the service’s first important missions was port security. The wartime increase in munitions shipments required manpower and assets to oversee this vital mission. Never before had the threat of massive destruction from explosives been so great. This was born out by an explosion that rocked New York City on July 31, 1916. The munitions  terminal on Black Tom Island, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from Manhattan, was a primary staging area for ordnance shipped to the war in Europe. Set off by German saboteurs, the blast killed several people and caused

terminal on Black Tom Island, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from Manhattan, was a primary staging area for ordnance shipped to the war in Europe. Set off by German saboteurs, the blast killed several people and caused property damage amounting to $1 billion in today’s currency. This attack quickly focused attention on the dangers of storing, loading and trans-shipping volatile explosives near major population centers.

property damage amounting to $1 billion in today’s currency. This attack quickly focused attention on the dangers of storing, loading and trans-shipping volatile explosives near major population centers.

In June 1917, after the Black Tom explosion, Congress passed the Espionage Act shifting responsibility for safety and movement of vessels in U.S. harbors from the Army Corps of Engineers to the Department of the Treasury. Treasury bestowed on the Coast Guard the power to protect merchant shipping from sabotage, safeguard waterfront property, supervise vessel movement s, establish anchorages and restricted areas, and regulate the loading and shipment of hazardous cargoes. It also gave the Coast Guard the right to control and remove people deemed security risks from ships. As a result, the service arrested merchant seamen aboard foreign merchant vessels interned in U.S. ports.

s, establish anchorages and restricted areas, and regulate the loading and shipment of hazardous cargoes. It also gave the Coast Guard the right to control and remove people deemed security risks from ships. As a result, the service arrested merchant seamen aboard foreign merchant vessels interned in U.S. ports.

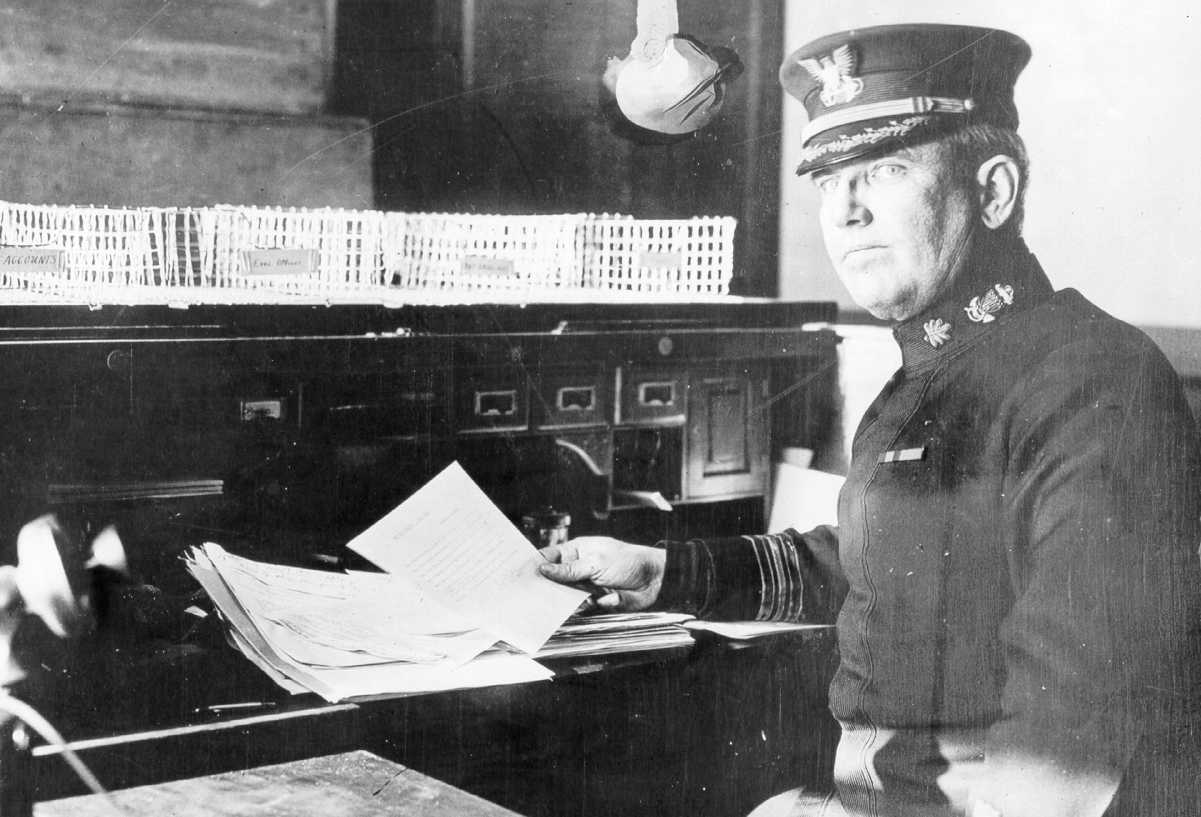

During the war, Capt. Godfrey Carden became the nation’s best-known Coast Guard officer and the term “captain of the port” was invented to describe his role as overseer of New York’s port security. Carden’s division was the service’s largest wartime command. In the span of one and a half years, Carden’s men oversaw the loading of 1,700 ships with more than 345 million tons of shells, smokeless powder, dynamite, ammunition, and other explosives. The Coast Guard also established captain-of-the-port offices in Philadelphia, Hampton Roads, Virginia, and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

port” was invented to describe his role as overseer of New York’s port security. Carden’s division was the service’s largest wartime command. In the span of one and a half years, Carden’s men oversaw the loading of 1,700 ships with more than 345 million tons of shells, smokeless powder, dynamite, ammunition, and other explosives. The Coast Guard also established captain-of-the-port offices in Philadelphia, Hampton Roads, Virginia, and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

Coast Guard officers held other important commands during World War I. Twenty-four of them commanded naval warships in the war zone, five commanded warships attached to the American Patrol detachment in the Caribbean, 23 commanded warships attached to Naval Districts, and five Coast Guard officers commanded large training camps. Shortly after hostilities ended, four Coast Guard officers were also assumed command troop transports bringing troops home from France. Officers not ass igned to command vessels or bases served in practically every phase of naval activity, including transports, cruisers, cutters, patrol vessels, in naval districts, as inspectors, and at training camps. Of the 223 Coast Guard officers who served, seven met their deaths as a result of enemy action.

igned to command vessels or bases served in practically every phase of naval activity, including transports, cruisers, cutters, patrol vessels, in naval districts, as inspectors, and at training camps. Of the 223 Coast Guard officers who served, seven met their deaths as a result of enemy action.

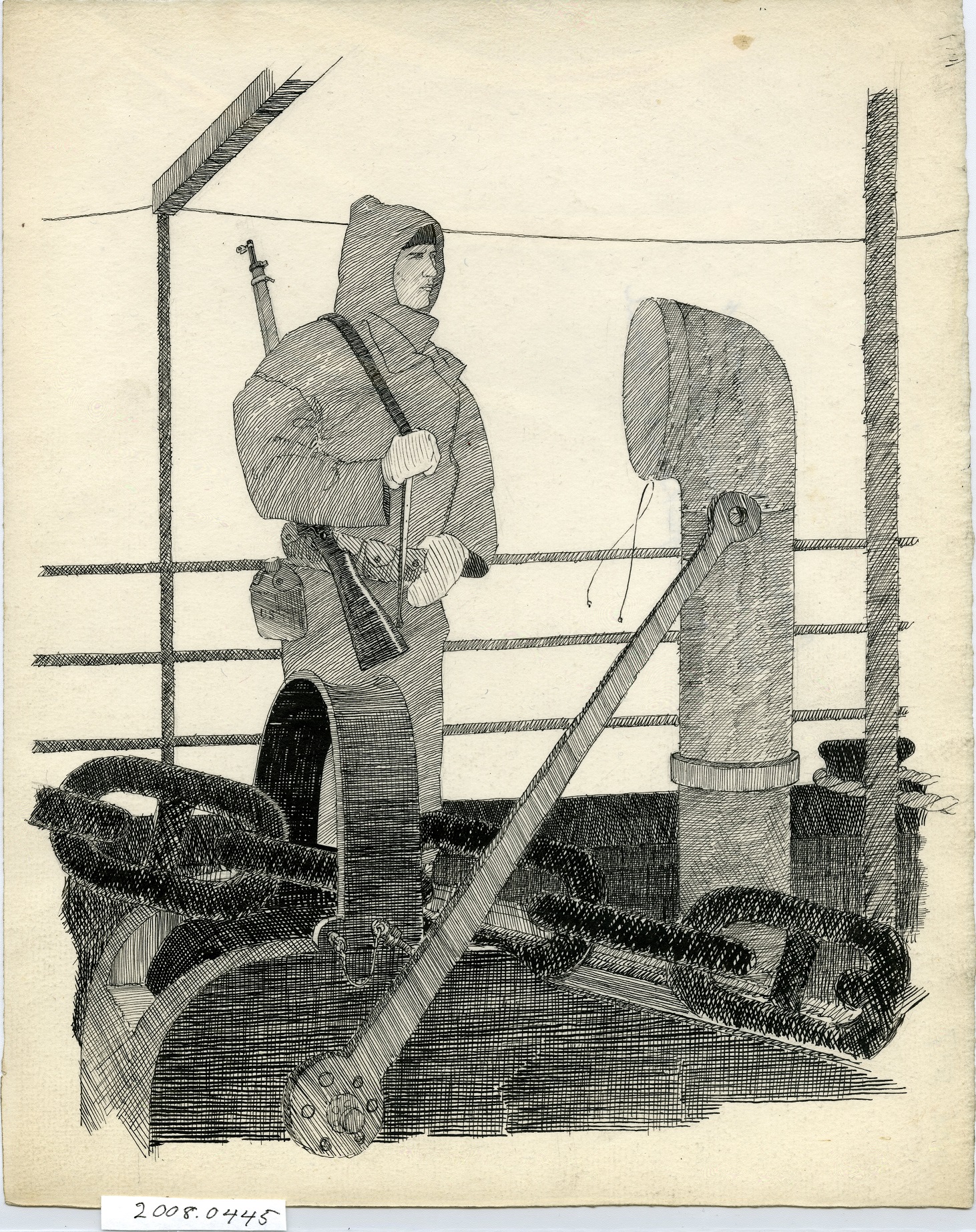

The Coast Guard was not limited to domestic duties during World War I, and soon vessels and personnel were called to serve overseas. In August and S eptember 1917, six Coast Guard cutters joined U.S. Naval forces in European waters. They constituted Squadron 2, Division 6, of the patrol forces for the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet based at Gibraltar. Throughout the war, these cutters escorted hundreds of vessels through the sub-infested waters between Gibraltar and the British Isles while others performed patrol and escort duties in the Mediterranean. Some high seas cutters also performed patrol and convoy escort duties in U.S. coastal waters, off Bermuda, in the Azores, in the Caribbean, and off the coast of Nova Scotia.

eptember 1917, six Coast Guard cutters joined U.S. Naval forces in European waters. They constituted Squadron 2, Division 6, of the patrol forces for the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet based at Gibraltar. Throughout the war, these cutters escorted hundreds of vessels through the sub-infested waters between Gibraltar and the British Isles while others performed patrol and escort duties in the Mediterranean. Some high seas cutters also performed patrol and convoy escort duties in U.S. coastal waters, off Bermuda, in the Azores, in the Caribbean, and off the coast of Nova Scotia.

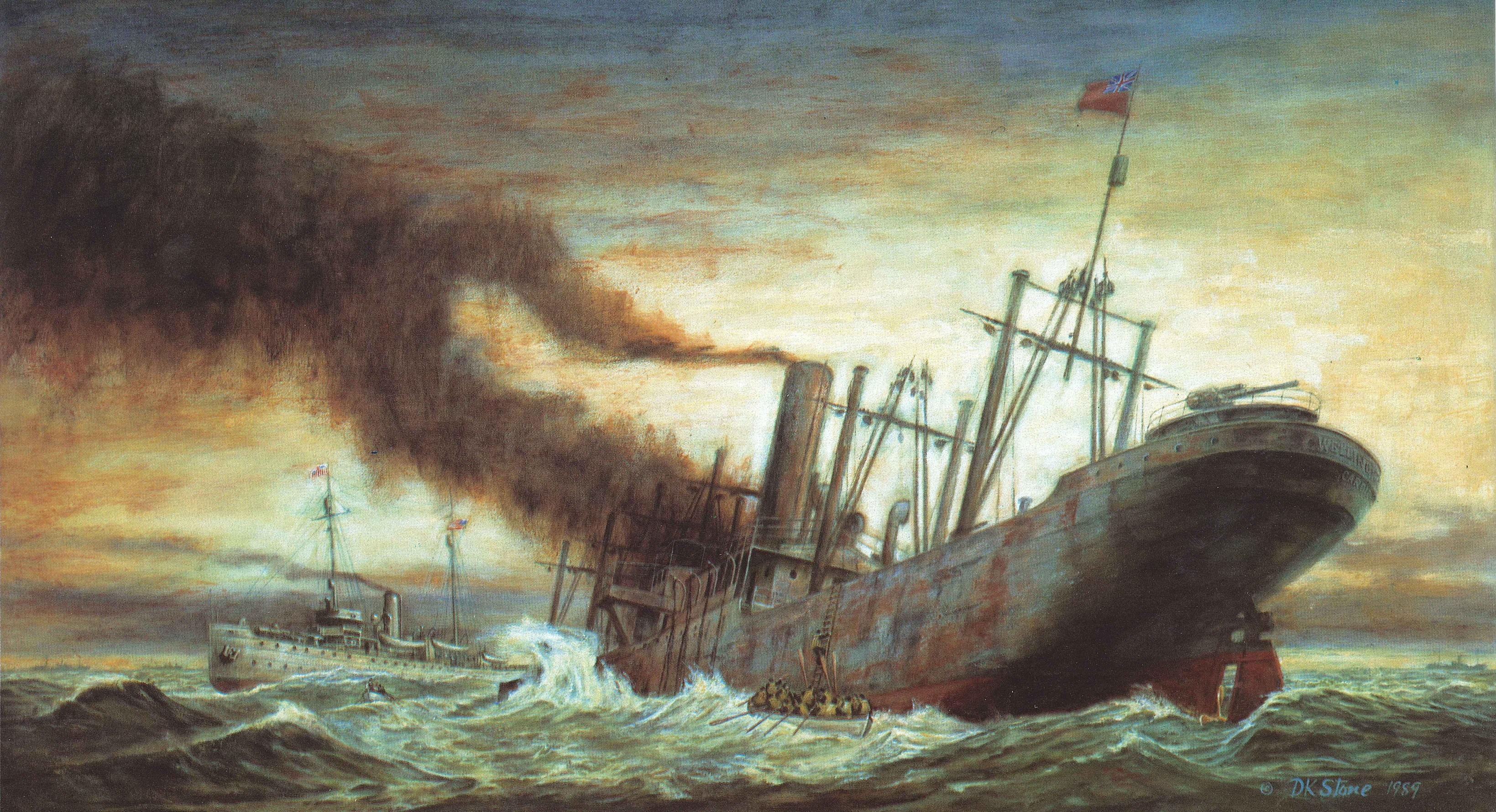

In addition to escort duty, cutters continued to perform their traditional missions. At 2:45 in the mornin g of March 25, 1918, the British naval sloop Cowslip steamed out of Gibraltar to meet a convoy escorted by Cutter Seneca. Cowslip was struck and almost broken in two by a torpedo from a German submarine. Warned to stay away because of the

g of March 25, 1918, the British naval sloop Cowslip steamed out of Gibraltar to meet a convoy escorted by Cutter Seneca. Cowslip was struck and almost broken in two by a torpedo from a German submarine. Warned to stay away because of the  presence of enemy submarines, Seneca followed the traditions of the service, and three times stopped to send off small boats in order to take on survivors. These boats succeeded in saving two officers and 79 enlisted men. In late June, Seneca saved 27 crewmembers of the torpedoed British merchant steamer Queen. And, when the British steamer Wellington was torpedoed in mid-September, a volunteer crew from Seneca attempted to save the vessel. The ship finally foundered on September 17th, and 11 Coast Guardsmen lost their lives trying to save it. In all, 20 of Seneca’s boarding party received the Navy Cross Medal, and one received the Distinguished Service Medal, making this event the most honored operation in service history.

presence of enemy submarines, Seneca followed the traditions of the service, and three times stopped to send off small boats in order to take on survivors. These boats succeeded in saving two officers and 79 enlisted men. In late June, Seneca saved 27 crewmembers of the torpedoed British merchant steamer Queen. And, when the British steamer Wellington was torpedoed in mid-September, a volunteer crew from Seneca attempted to save the vessel. The ship finally foundered on September 17th, and 11 Coast Guardsmen lost their lives trying to save it. In all, 20 of Seneca’s boarding party received the Navy Cross Medal, and one received the Distinguished Service Medal, making this event the most honored operation in service history.

At home, the war required vi gilance on the part of the service’s boat stations. For example, on August 16, 1918, while steaming northward along the Atlantic coast, the British steamship Mirlo struck an enemy laid mine off of North Carolina. Mirlo’s cargo of gasoline and refined oil spread over the sea and ignited. Chief Boatswain John Midgett and the Chicamacomico Coast Guard Station crew launched their motor surfboat and forced their way into the mass of fire and wreckage to rescue six men clinging to a capsized lifeboat. Midgett and his men fought the flames and intense heat to pick up two more boatloads of men, landing them ashore safely through heavy surf. Altogether, the Chicamacomico boat crew saved 42 people and all of the men were awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal.

gilance on the part of the service’s boat stations. For example, on August 16, 1918, while steaming northward along the Atlantic coast, the British steamship Mirlo struck an enemy laid mine off of North Carolina. Mirlo’s cargo of gasoline and refined oil spread over the sea and ignited. Chief Boatswain John Midgett and the Chicamacomico Coast Guard Station crew launched their motor surfboat and forced their way into the mass of fire and wreckage to rescue six men clinging to a capsized lifeboat. Midgett and his men fought the flames and intense heat to pick up two more boatloads of men, landing them ashore safely through heavy surf. Altogether, the Chicamacomico boat crew saved 42 people and all of the men were awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal.

Naval aviati on expanded rapidly during the war. Eight Coast Guardsmen had earned their wings by the onset of the war, and all participated in the war effort. Six were assigned as commanding officers of major commands. Coast Guard lieutenants became commanding officers of the Naval air stations at Ille Tudy, France, Chatham, Massachusetts, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Key West, Florida and the enlisted flight training school at Pensacola, Florida. In 1919, the Coast Guard also provided the first pilot to cross the Atlantic, Lt. Elmer Stone, in the Navy’s NC-4 flying boat.

on expanded rapidly during the war. Eight Coast Guardsmen had earned their wings by the onset of the war, and all participated in the war effort. Six were assigned as commanding officers of major commands. Coast Guard lieutenants became commanding officers of the Naval air stations at Ille Tudy, France, Chatham, Massachusetts, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Key West, Florida and the enlisted flight training school at Pensacola, Florida. In 1919, the Coast Guard also provided the first pilot to cross the Atlantic, Lt. Elmer Stone, in the Navy’s NC-4 flying boat.

On Monday, November 11, 1918, Germany signed the armistice ending World War I. The conflict proved the first true test of the Coast Guard’s military capability. Altogether, over 8,800 men and women served in the Coast Guard during the conflict. The service’s heroes received two Distinguished Service Medals, eight Gold Lifesaving Medals, almost a dozen foreign honors. They also r eceived nearly 50 Navy Cross Medals, dozens more than were awarded to Coast Guardsmen in World War II.

eceived nearly 50 Navy Cross Medals, dozens more than were awarded to Coast Guardsmen in World War II.

World War I served as a baptism of fire for the Coast Guard. During the war’s nearly 19 months, the service lost five ships and nearly 200 men. These ships included two combat losses. On August 6, 1918, U-140 sank the Diamond Shoals Lightship after its crew transmitted to shore the location of the marauding enemy submarine, but no lives were lost. On September 26, 1918,  after escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to the United Kingdom, Cutter Tampa was torpedoed by UB-91. The cutter quickly sank killing all 130 people aboard, including four U.S. Navy men, 15 Royal Navy personnel and 111 Coast Guard officers and men. It proved America’s greatest naval loss of life from combat during the war. An additional 81 Coast Guardsmen lost their lives in the line of duty during the War.

after escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to the United Kingdom, Cutter Tampa was torpedoed by UB-91. The cutter quickly sank killing all 130 people aboard, including four U.S. Navy men, 15 Royal Navy personnel and 111 Coast Guard officers and men. It proved America’s greatest naval loss of life from combat during the war. An additional 81 Coast Guardsmen lost their lives in the line of duty during the War.

During the war, the Coast Guard performed its traditional missio ns of search and rescue, maritime interdiction, law enforcement, humanitarian response, and port security. The service also undertook new missions of shore patrol, marine safety, and convoy escort duty and played a vital role in naval aviation, troop transport operations and overseas naval missions. By war’s end, these assignments had become a permanent part of the Coast Guard’s defense readiness mission. This baptism of fire cemented the service’s place among American military agencies and prepared it for the challenges it would face during the Rum War of Prohibition and later in World War II.

ns of search and rescue, maritime interdiction, law enforcement, humanitarian response, and port security. The service also undertook new missions of shore patrol, marine safety, and convoy escort duty and played a vital role in naval aviation, troop transport operations and overseas naval missions. By war’s end, these assignments had become a permanent part of the Coast Guard’s defense readiness mission. This baptism of fire cemented the service’s place among American military agencies and prepared it for the challenges it would face during the Rum War of Prohibition and later in World War II.