Jan. 15, 2021 —

On Thursday, April 17, 1851, the lighthouse at Minots Ledge collapsed into the sea a mile off the Massachusetts Coast killing both its keepers. Located south of Boston, the failure of this brand new lighthouse had been in the making for years.

Local Native Americans believed that evil spirits inhabited Minot’s Ledge and the rock outcropping roiled-up stormy seas whenever they failed to provide o fferings to the spirits. European settlement of the area brought with it ships. Sea captains unfamiliar with local waters would sail too close to the uncharted rocks when approaching Boston Harbor and lose their vessels to the ledge. A vessel owned by George Minot was one of these lost ships, so the ledge took its name from the unfortunate ship owner. Over 40 vessels wrecked on the ledge before 1841 and at least 40 lives were lost prior to 1850.

fferings to the spirits. European settlement of the area brought with it ships. Sea captains unfamiliar with local waters would sail too close to the uncharted rocks when approaching Boston Harbor and lose their vessels to the ledge. A vessel owned by George Minot was one of these lost ships, so the ledge took its name from the unfortunate ship owner. Over 40 vessels wrecked on the ledge before 1841 and at least 40 lives were lost prior to 1850.

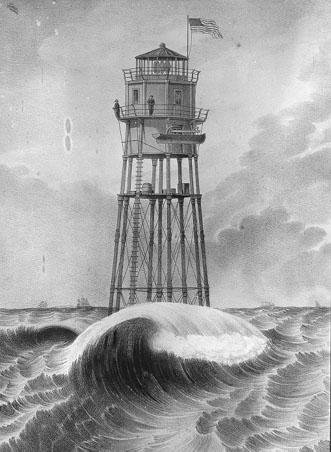

Finally,  in the early 1840s, the U.S. Lighthouse Service decided to erect a lighthouse on Minot’s Ledge. The ledge sits a mile offshore. All previous U.S. lighthouses had been built on dry land, so the service sent an engineer to England to research offshore lighthouses in that country. He returned and designed a structure of eight iron pilings and a central iron column supporting a 30-ton lantern room and keeper’s quarters complex. At that time, the theory behind the structure held that heavy seas would find little resistance from iron stilts where heavy seas could collapse a monolithic tower structure.

in the early 1840s, the U.S. Lighthouse Service decided to erect a lighthouse on Minot’s Ledge. The ledge sits a mile offshore. All previous U.S. lighthouses had been built on dry land, so the service sent an engineer to England to research offshore lighthouses in that country. He returned and designed a structure of eight iron pilings and a central iron column supporting a 30-ton lantern room and keeper’s quarters complex. At that time, the theory behind the structure held that heavy seas would find little resistance from iron stilts where heavy seas could collapse a monolithic tower structure.

The new Minots Ledge Light began service on New Year’s Day 1850. From the beginning, the structure showed signs of structural weakness and swayed with the action of the waves below. The iron support structure was constantly tightened and re-worked to stop the swaying, but nothing could alleviate the problem. In fear for his life, Minots Light’s first keeper resigned after 10 months and his successor tried his best to improve the structural integrity of the light.

In 1851, a mid-April storm struck the coast and continued working the structure for days. Eventually, the central iron column snapped placing the load-bearing burden on the  eight outer stilts. With the seas churning beneath the lighthouse, the two keepers were trapped in the swaying quarters. Within hours, the eight stilts began the sickening process of snapping one-by-one. In the early morning of April 17th, the keepers took their lives in their hands and jumped into the stormy seas as the lantern room and quarters slid into the sea. One of the men managed to swim to a nearby rock only to die of exposure, while the other drowned in the surf and washed ashore.

eight outer stilts. With the seas churning beneath the lighthouse, the two keepers were trapped in the swaying quarters. Within hours, the eight stilts began the sickening process of snapping one-by-one. In the early morning of April 17th, the keepers took their lives in their hands and jumped into the stormy seas as the lantern room and quarters slid into the sea. One of the men managed to swim to a nearby rock only to die of exposure, while the other drowned in the surf and washed ashore.

In the span of a year, the lighthouse that began as the engineering marvel of its day had become one of the great technological failures in U.S. Lighthouse Service history. However, within 10 years, a new engineering marvel would spring-up in its place. Between 1851 and 1860, a lightship guarded the ledge. Meanwhile, plans for a 100-foot lighthouse were drawn-up by the service and model makers built the proposed tower in miniature.

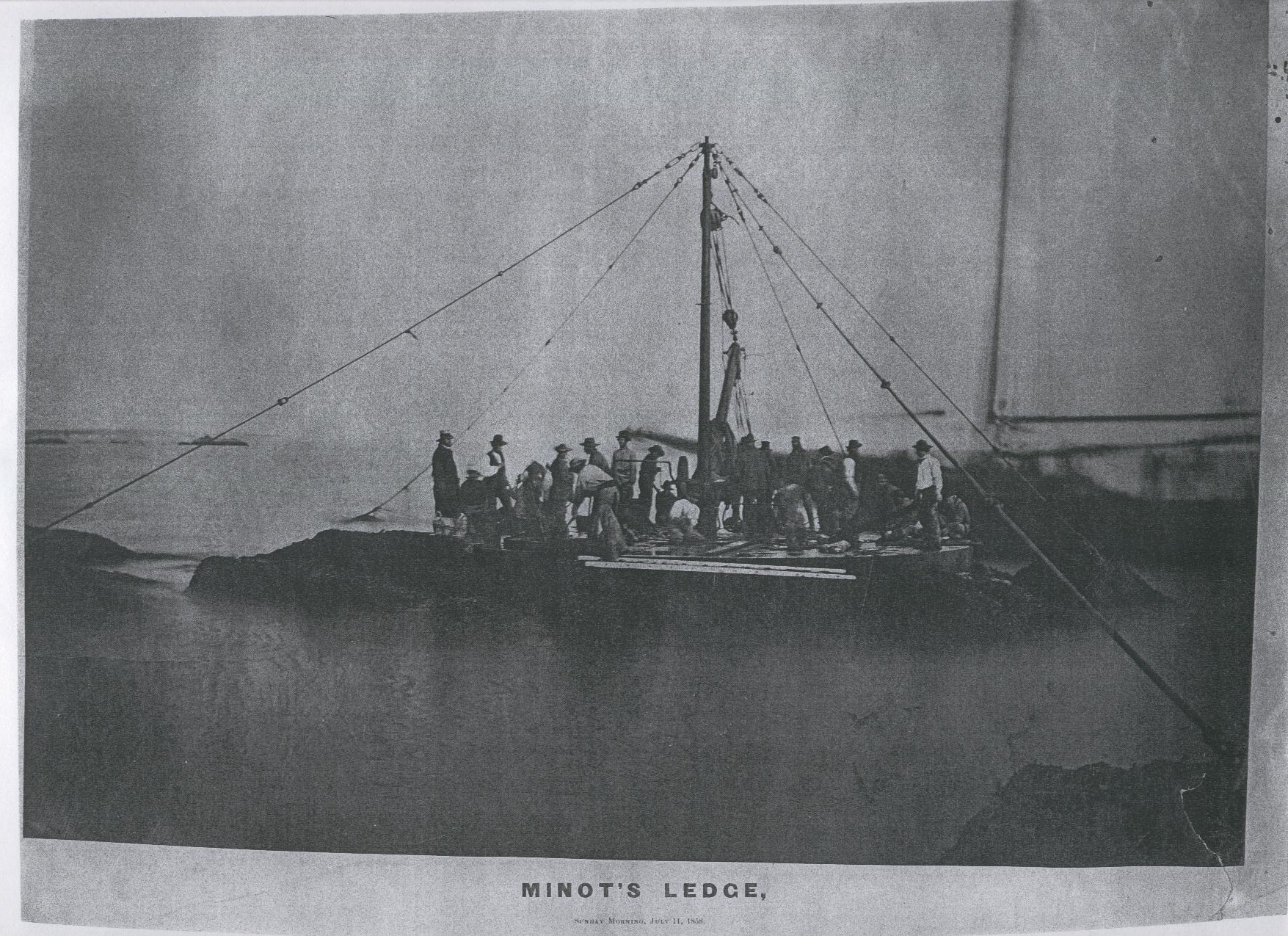

The Lighthouse Service approved the tower design, and construction began in April 1855. The new lighthouse would be built of stone so the ledge had to be cut down to receive the foundation blocks. In June, the iron stumps of the first tower were removed and 20-foot iron anchoring shafts were set in the holes where the old iron pilings had stood. The large hole left by the central column was left open to form a cavity for storing drinking water. At the same time, crews began cutting and assembling granite blocks on Government Island, near Cohasset.

In January 1857, during a severe storm, the sailing barque New Empire struck the construction framework demolishing the project’s construction scaffolding. The builders erected a temporary cofferdam from sandbags, so the foundation blocks, laid two feet under the surface of low tide, could be cemented to the ledge.

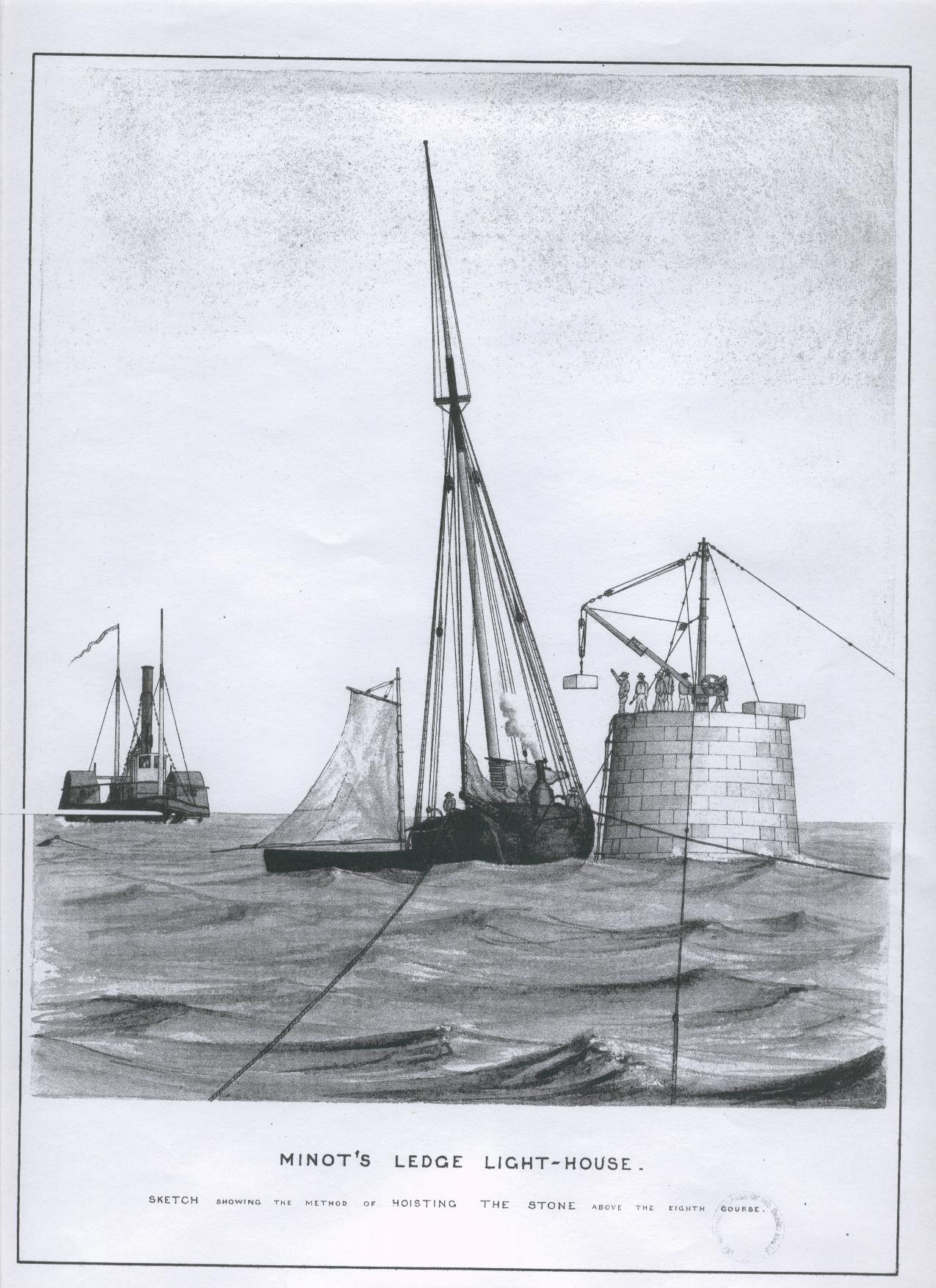

In the spring of 1857, the work began again and the first stone was finally laid on July 9th. Seven massive blocks formed the foundation. Strap iron between each stone course kept the two-ton granite blocks apart while the cement hardened. In addition, the service’s first steam-powered vessel, Lighthouse Tender Van Santvoort, became the project’s support vessel providing reliable delivery of stones and construction materials and transportation for crews to and from shore.

In the spring of 1857, the work began again and the first stone was finally laid on July 9th. Seven massive blocks formed the foundation. Strap iron between each stone course kept the two-ton granite blocks apart while the cement hardened. In addition, the service’s first steam-powered vessel, Lighthouse Tender Van Santvoort, became the project’s support vessel providing reliable delivery of stones and construction materials and transportation for crews to and from shore.

In late 1859, the 32nd stone course, located 62 feet above low water, was set in place. The final stone was laid on June 29, 1860. The lighthouse was equipped and ready by mid-August 1860, and first lighted on August 22nd and began regular service on November 15th when Keeper Joshua Wheeler and two assistants began their duties. The granite tower had taken five years to complete at a cost of nearly $330,000, or over $5,000,000 in today’s dollars.

Minots Ledge Lighthouse has withstood every subsequent gale with the largest waves causing only strong vibrations.  On some occasions, the seas have actually swept over the top of the lighthouse causing leaky windows or a few cracked lens prisms. In 1894, a new flashing lantern was installed with a one-four-three flash, which spectators on shore found contained the same numeric count as the words “I love you.” As a result, Minots Ledge became known as the “Lover’s Light.” In 1947, the service automated the lighthouse and, today, its 45,000 candlepower light is visible for 15 miles.

On some occasions, the seas have actually swept over the top of the lighthouse causing leaky windows or a few cracked lens prisms. In 1894, a new flashing lantern was installed with a one-four-three flash, which spectators on shore found contained the same numeric count as the words “I love you.” As a result, Minots Ledge became known as the “Lover’s Light.” In 1947, the service automated the lighthouse and, today, its 45,000 candlepower light is visible for 15 miles.

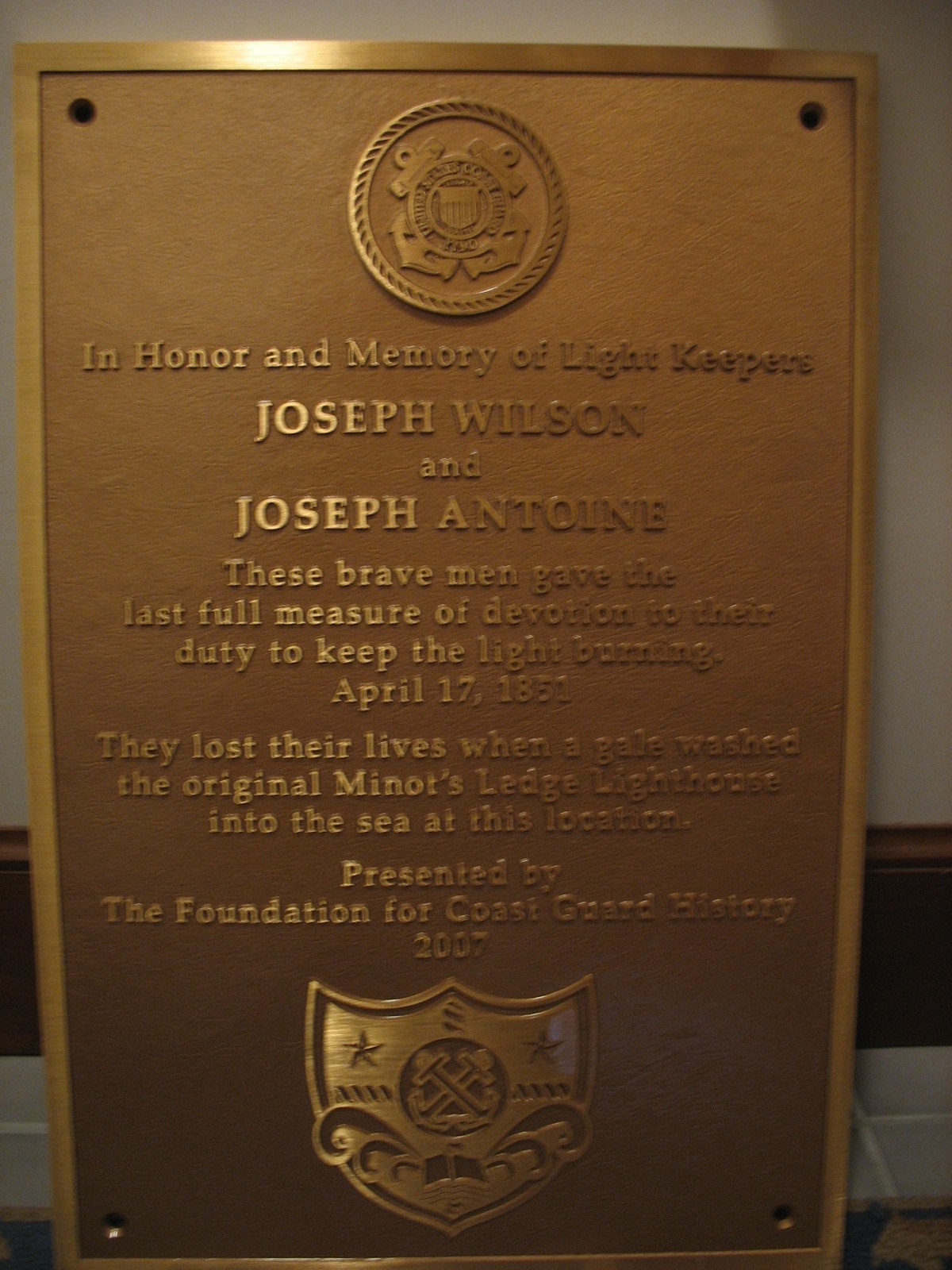

In June 2007, an expedition supported by personnel and assets from over a dozen local, municipal, state and federal agencies returned to the site of the 1851 lighthouse collapse. From the decks of Coast Guard buoy tender Abbie Burgess, divers surveyed the site and located artifacts left from the original structure. In addition, the party placed a memorial plaque on the ledge honoring the two keepers who died when the iron structure sank in to the sea. The devotion to duty exhibited by these two brave men, and all keepers who have died while keeping the light, remains an important chapter in the Coast Guard’s long blue line.

to the sea. The devotion to duty exhibited by these two brave men, and all keepers who have died while keeping the light, remains an important chapter in the Coast Guard’s long blue line.