Dec. 31, 2020 —

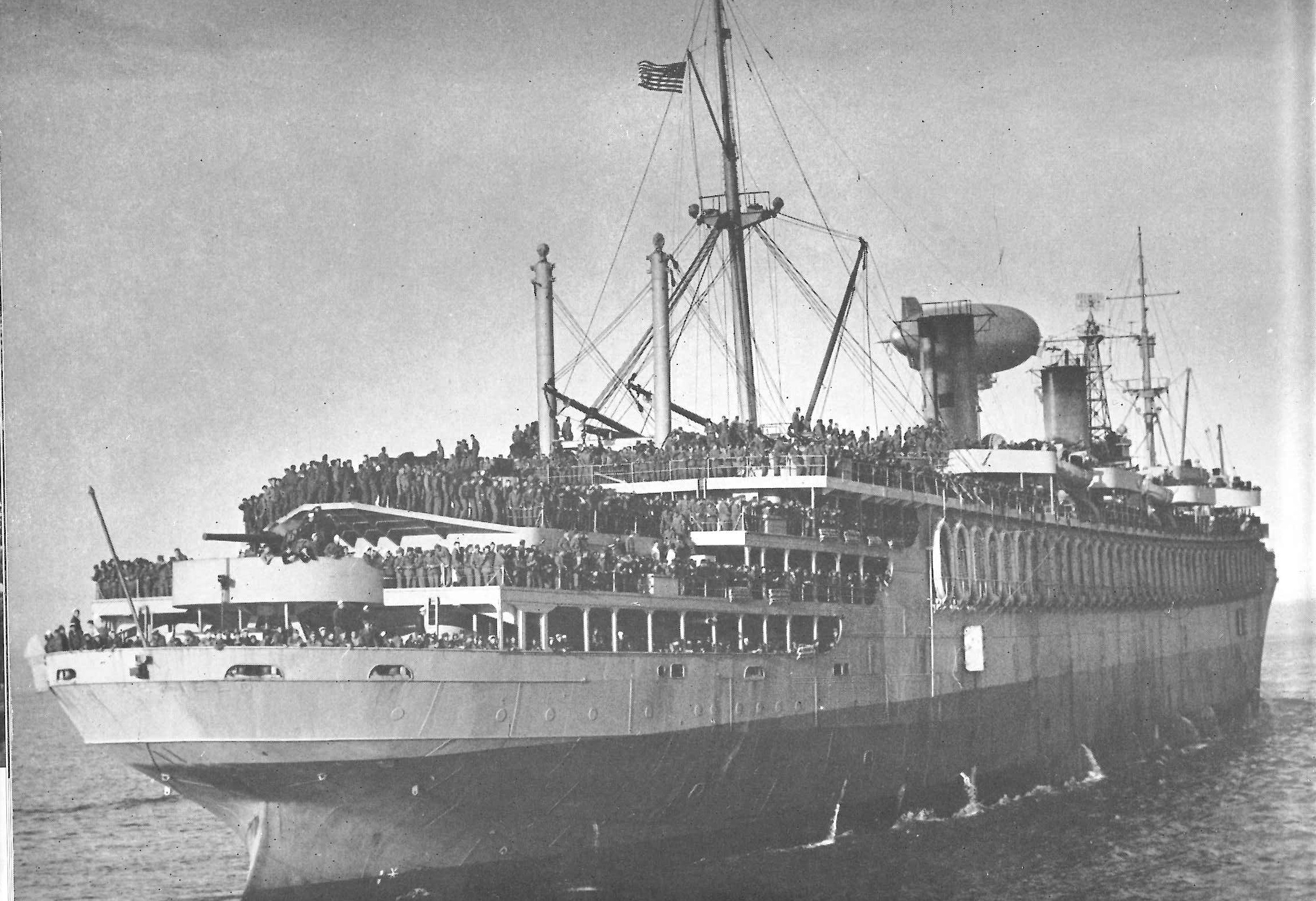

In World War II, th e USS Wakefield (AP-21) served as a fast troop transport whose role was to deliver military personnel and supplies to the war front. Commanded by U.S. Coast Guard officers and operated by Coast Guard personnel, this troopship could carry over 7,000 passengers, far more than most transports at that time.

e USS Wakefield (AP-21) served as a fast troop transport whose role was to deliver military personnel and supplies to the war front. Commanded by U.S. Coast Guard officers and operated by Coast Guard personnel, this troopship could carry over 7,000 passengers, far more than most transports at that time.

Launched in December 1931 as the luxury liner S.S. Manhattan, the Wakefield originally served in the United States Lines. At over 20 knots service speed, the liner was the fastest passenger ship in the world and made scheduled runs from New York to Hamburg into the late 1930’s. After war broke out, the vessel brought American nationals back from Europe. The ship was converted to a troop transport at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, renamed the Wakefield (after George Washington’s Wakefield Mansion) and commissioned with its Coast Guard crew in June 1941.

The Wakefield was 705 feet long with an 86-foot beam and a 31-foot draft. It was over 24,000 gross tons with a 33,650-ton displacement. The transport had powerful steam turbines driving two screws that could propel the vessel at high speed. For war service, the vessel was painted battleship gray and equipped with numerous rubber life rafts in case of loss or sinking. The ship was manned with a complement of 50 officers and 900 enlisted men, and a detachment of 30 Marines.

transport had powerful steam turbines driving two screws that could propel the vessel at high speed. For war service, the vessel was painted battleship gray and equipped with numerous rubber life rafts in case of loss or sinking. The ship was manned with a complement of 50 officers and 900 enlisted men, and a detachment of 30 Marines.

In December 1941, while transporting Canadian troops from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Capetown, South Africa, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor bringing the U.S. into the war, so Wakefield was diverted to Singapore. On January 30, 1942, while moored in Singapore, the transport was bombed by Japanese aircraft. A bomb penetrated the ship’s upper decks and exploded in the ship’s sickbay killing five Coast Guardsmen and injuring nine. These casualties were among the first suffered by the Coast Guard in World War II.

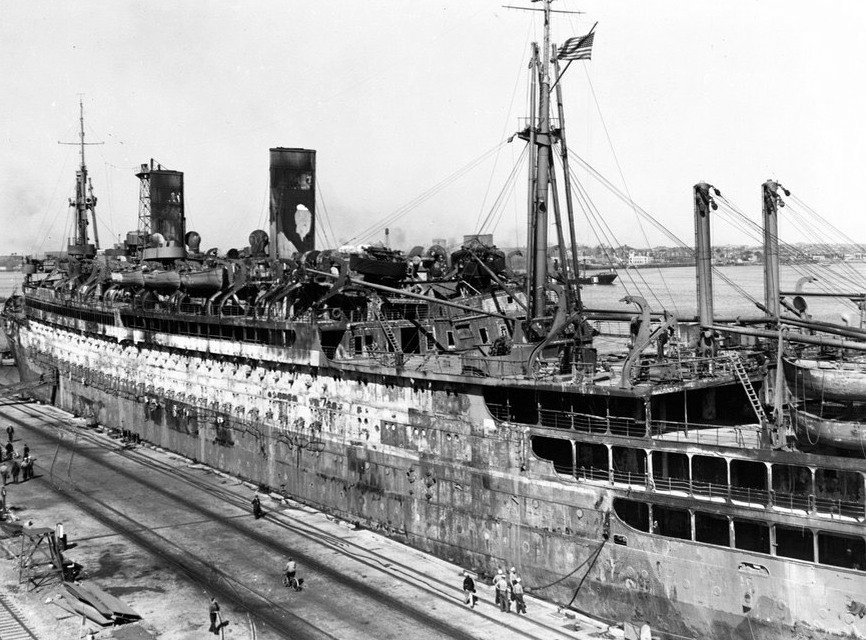

On September 3, 1942, on a return trip from England to New York, fire broke out on board Wakefield. Filipino Ship’s Steward Francisco Siladio was the only Coast Guardsman lost in the conflagration, becoming one of the first Asian cutterman lost in the line of duty. The ship’s burned-out hulk was  towed to the Boston Navy Yard and the transport temporarily decommissioned. The Wakefield had to be completely rebuilt.

towed to the Boston Navy Yard and the transport temporarily decommissioned. The Wakefield had to be completely rebuilt.

In February 1944, Wakefield was re-commissioned with Coast Guard Capt. Roy Raney in command. On April 13th, with 7,000 Army troops aboard, the transport left on the first of many trips from Boston to Liverpool. Referred to as the “B [oston] & L [iverpool] Ferry,” this 18-day round trip became a regular transatlantic run for the Wakefield.

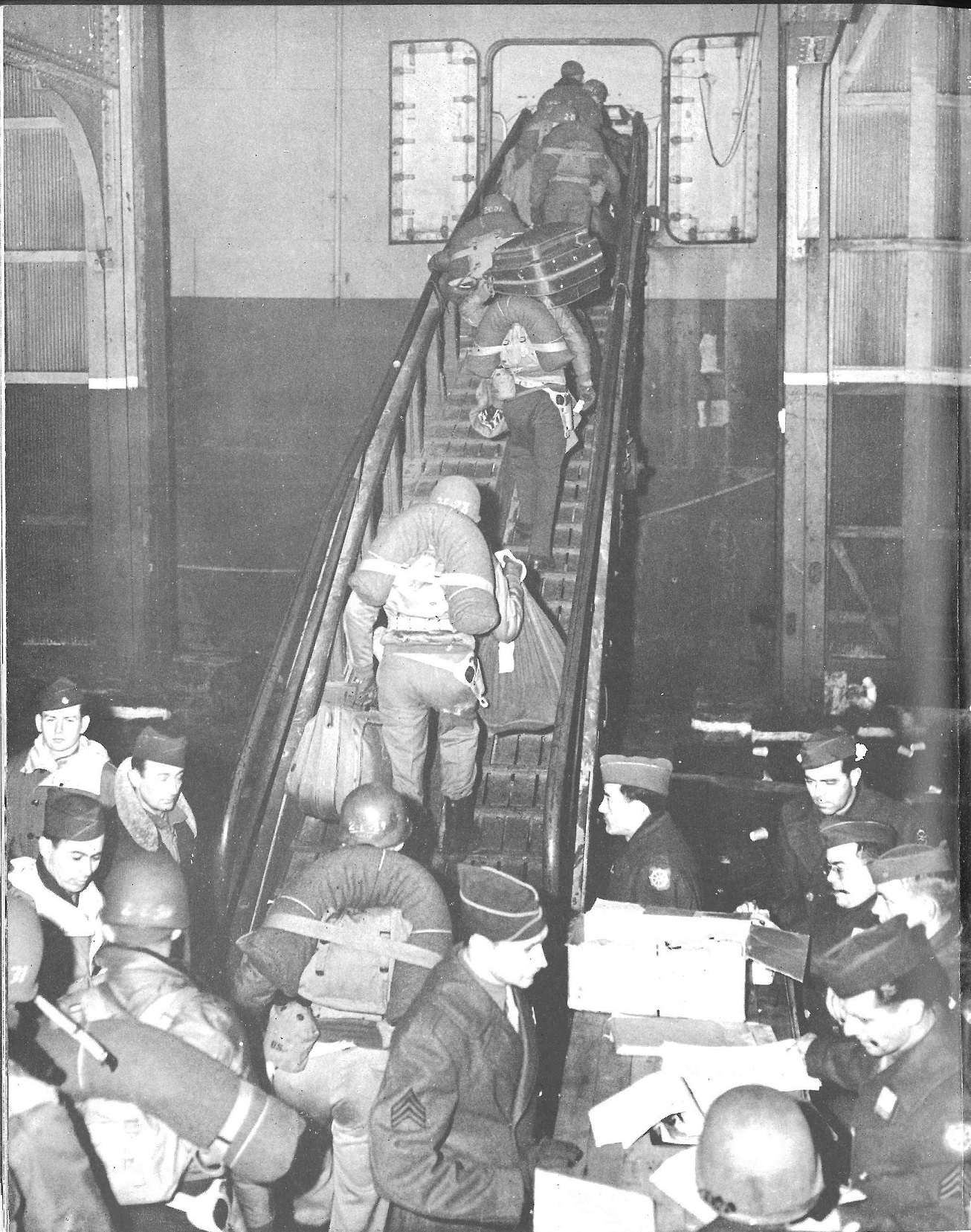

In Boston, loading troops, their gear and supplies took most of a day. Passenger trains would pull onto the docks and unload thousands of men to board the Wakefield. The troopship also loaded nearly 20,000 bags of mail for personnel in the European Theater of Operations. The transport could load 1,200 troops per hour with each man getting an assignment card indicating the location of his bunk. The card was also used as a meal ticket indicating the dining schedule. On the reverse side of the card were listed ship’s rules for general quarters, fire drills, and abandoning ship.

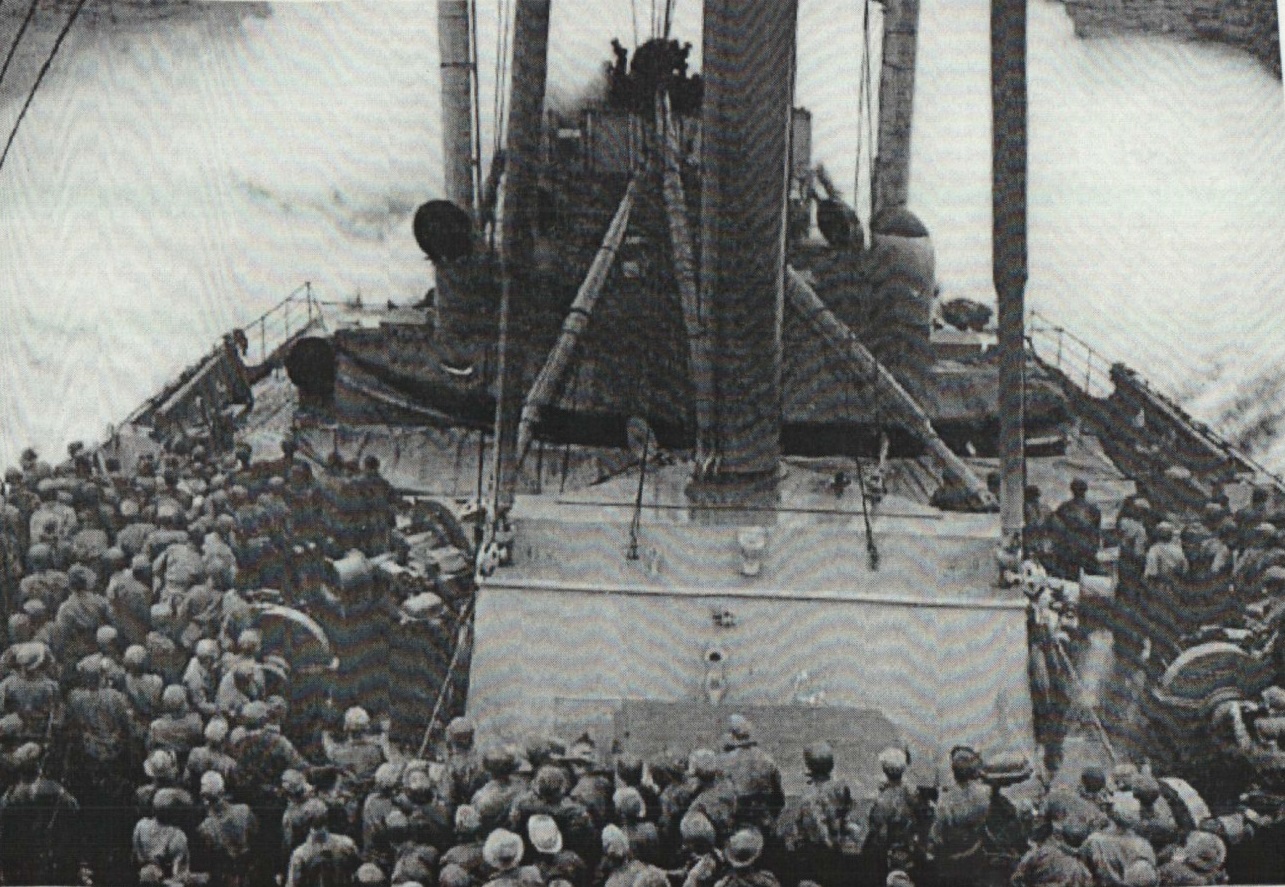

The Navy kept Wakefield’s departures a secret. Troops were not allowed to leave their bunk areas until the afternoon of the first day at sea. Bunks below decks were stacked five high with only the top man able to sit upright. In sleeping quarters, the aisles were narrow and often crammed with gear and Wakefield’s complement of Marines kept these spaces in order.

Each morning after leaving port, crew and passengers drilled at general quarters with guns manned. Wakefield’s armament varied at times, but normally included a five-inch dual-purpose gun in the bow and two on the stern. It also had three three-inch dual-purpose gun mounts, four 40 mm anti-aircraft guns, numerous 20 mm anti-aircraft guns, and eight .50 cal machine guns.

Troops wore inflatable life belts at all times and ate two meals a day standing-up cafeteria-style. The soldiers moved in four chow lines with 1,000 troops fed every 20 minutes. The galley cooked food in large pot kettles with dehydrated potatoes and eggs the staple food as well as toast, oatmeal and coffee. Every day, the troops consumed 2,500 loaves of bread and hundreds of pounds of butter. The Coast Guard crew dined in a separate mess hall.

The Wakefield produced 90,000 gallons of freshwater daily for washing, but there were days when saltwater was used for washing with Hershey’s Soap. Latrines were a series of outhouse like holes over a galvanized metal trough irrigated from a large pipe at one end sloped to drain at the other. The decks had to be hosed-down on a regular basis due to seasick troops.

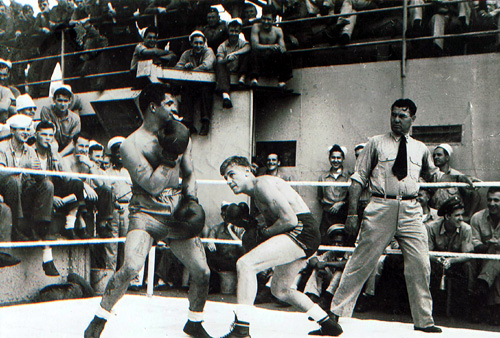

Aboard Wakefield, the troops entertained themselves on deck with cards, reading, smoking, gambling, music and loafing. Coast  Guard jazz bands played music for jitterbug dancing and crew members occasionally played the bagpipes. On one crossing, heavyweight boxer and Coast Guard officer, Jack Dempsey, refereed boxing matches. Chaplains held Protestant and Catholic services. There were also unit exercises for the troops. The ship’s canteen sold candy, peanuts and cigarettes. Since the ship had a modern ventilation system, smoking was even allowed below decks.

Guard jazz bands played music for jitterbug dancing and crew members occasionally played the bagpipes. On one crossing, heavyweight boxer and Coast Guard officer, Jack Dempsey, refereed boxing matches. Chaplains held Protestant and Catholic services. There were also unit exercises for the troops. The ship’s canteen sold candy, peanuts and cigarettes. Since the ship had a modern ventilation system, smoking was even allowed below decks.

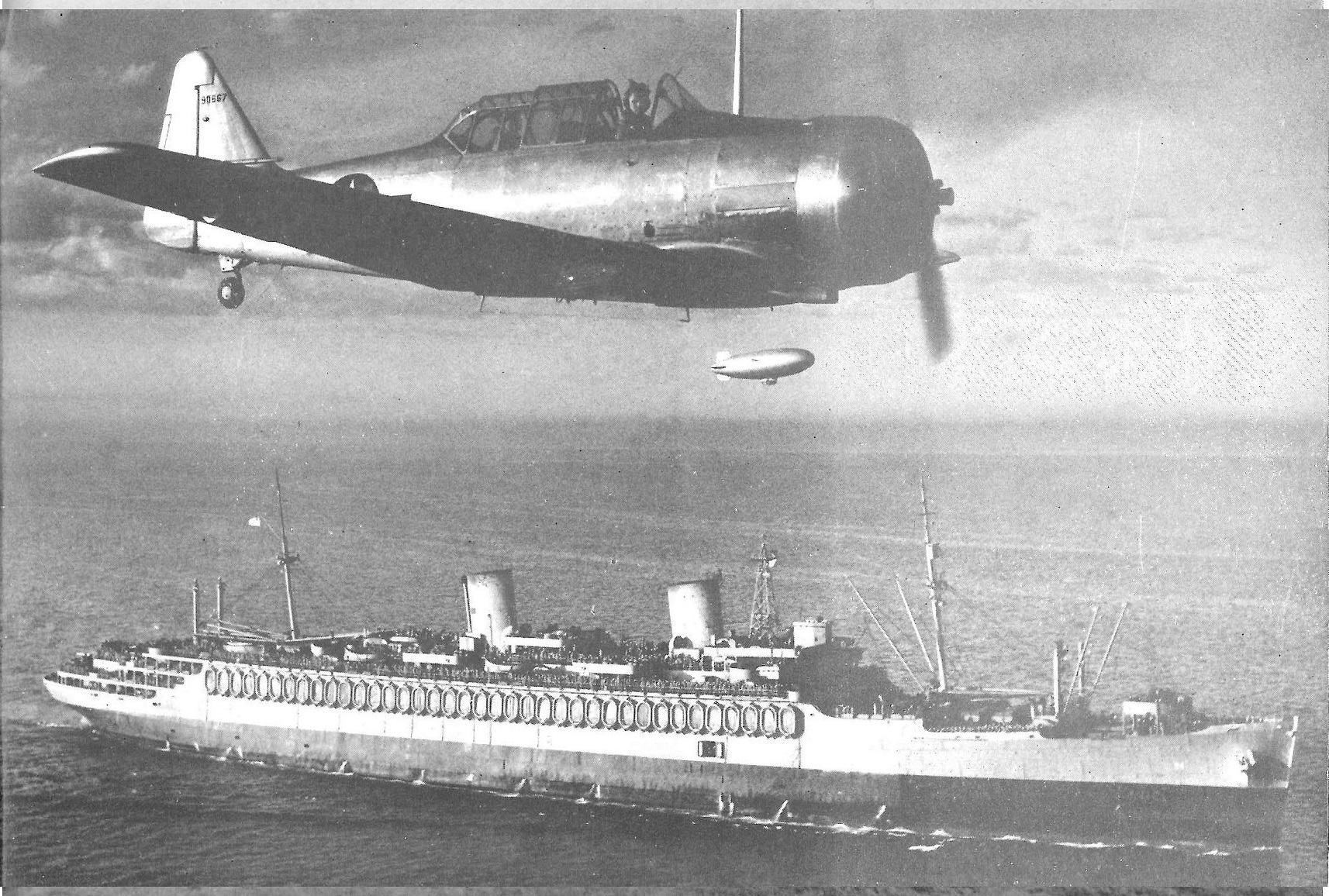

Throughout its World War II career, Wakefield was never caught by U-boats or Nazi aircraft. While in U.S. waters, the transport was guarded by naval vessels, aircraft and blimps. On the high seas, it did not transit in a convoy, but relied on its high speed, and irregular zigzag pattern to elude and outrun Nazi U-Boats. The vessel had radar and observed complete radio silence at sea, receiving messages but not transmitting them. Wakefield crew members considered their greatest hazard to be North Atlantic storms. During one storm, the bow gun crew had to be evacuated before the gun washed overboard.

Wakefield’s crossings from Boston to Liverpool took four to five days. The troopship typically remained unescorted until Royal Navy ships greeted it in British waters. After their last meal on board, departing American troops were issued K-rations for the trip to their next assignment. In Liverpool, unloading and re-loading for the return trip took three days.

In the build-up to 1944’s D-Day, the Wakefield played a vital role in ferrying troops to the U.K., including U.S. Army, Army Air  Corps, and Army nurses. After D-Day, the transport shipped captured German prisoners of war (POW) back to the U.S. The troopship also served as a casualty-evacuation vessel bringing back wounded GIs and treating them in the transport’s 92-bed sickbay staffed by five medical officers and 14 pharmacist mates.

Corps, and Army nurses. After D-Day, the transport shipped captured German prisoners of war (POW) back to the U.S. The troopship also served as a casualty-evacuation vessel bringing back wounded GIs and treating them in the transport’s 92-bed sickbay staffed by five medical officers and 14 pharmacist mates.

Wakefield made 23 roundtrips in the Atlantic and an additional three in the Pacific. By the end of the war in Europe, the troopship brought GIs home to Boston from the French ports of Marseille, Le Havre, and Cherbourg, as well as Taranto, Italy, and Oran, Algeria. After the ship’s 1942 fire and re-commissioning, it transported a total of 110,563 troops to Europe and Asia, and returned 104,674 Americans and German POWs to the U.S.

Wakefield made 23 roundtrips in the Atlantic and an additional three in the Pacific. By the end of the war in Europe, the troopship brought GIs home to Boston from the French ports of Marseille, Le Havre, and Cherbourg, as well as Taranto, Italy, and Oran, Algeria. After the ship’s 1942 fire and re-commissioning, it transported a total of 110,563 troops to Europe and Asia, and returned 104,674 Americans and German POWs to the U.S.

In May 1946, the Wakefield was moored in New York and decommissioned in June. The transport was laid up in reserve until 1959 and scrapped in 1964. Wakefield was one of the many transports operated by the Coast Guard in World War II and supported the Coast Guard’s long blue line of service to the nation.