Dec. 18, 2020 —

What a way to fight a war—kill all the kids and the next day is routine as usual.

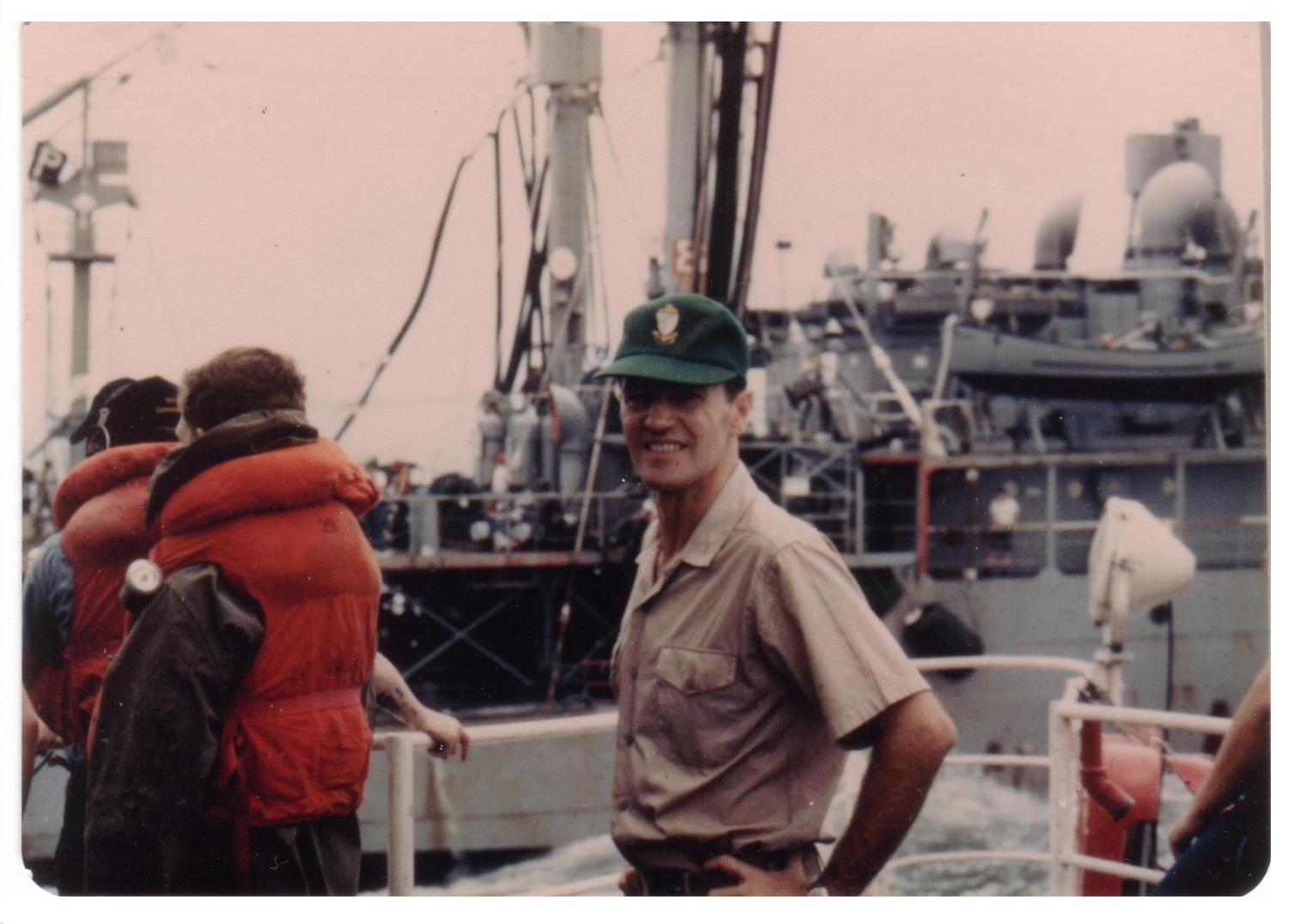

Chief Hospital Corpsman Joseph “Doc” White, 1970

[Editor’s note: This contains descriptions of war. Some of the material may be triggering for some readers. Also, this essay is transcribed from the original article written by Chief White with only light editing. A few words have been inserted in brackets to clarify meaning, however, the text remains largely unchanged. The term “American Healer” was used by the Vietnamese to describe American corpsmen who provided medical care for local villagers.]

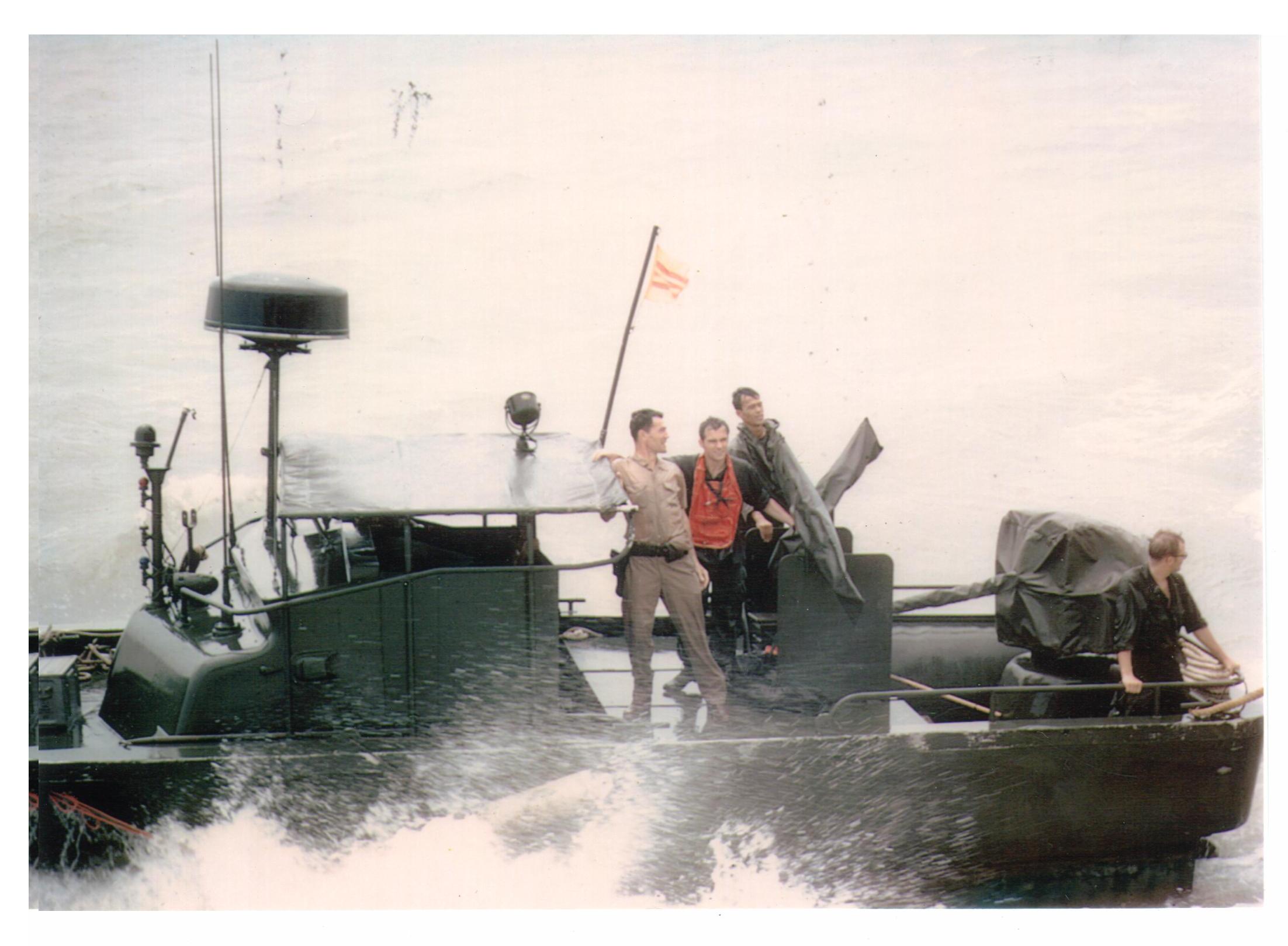

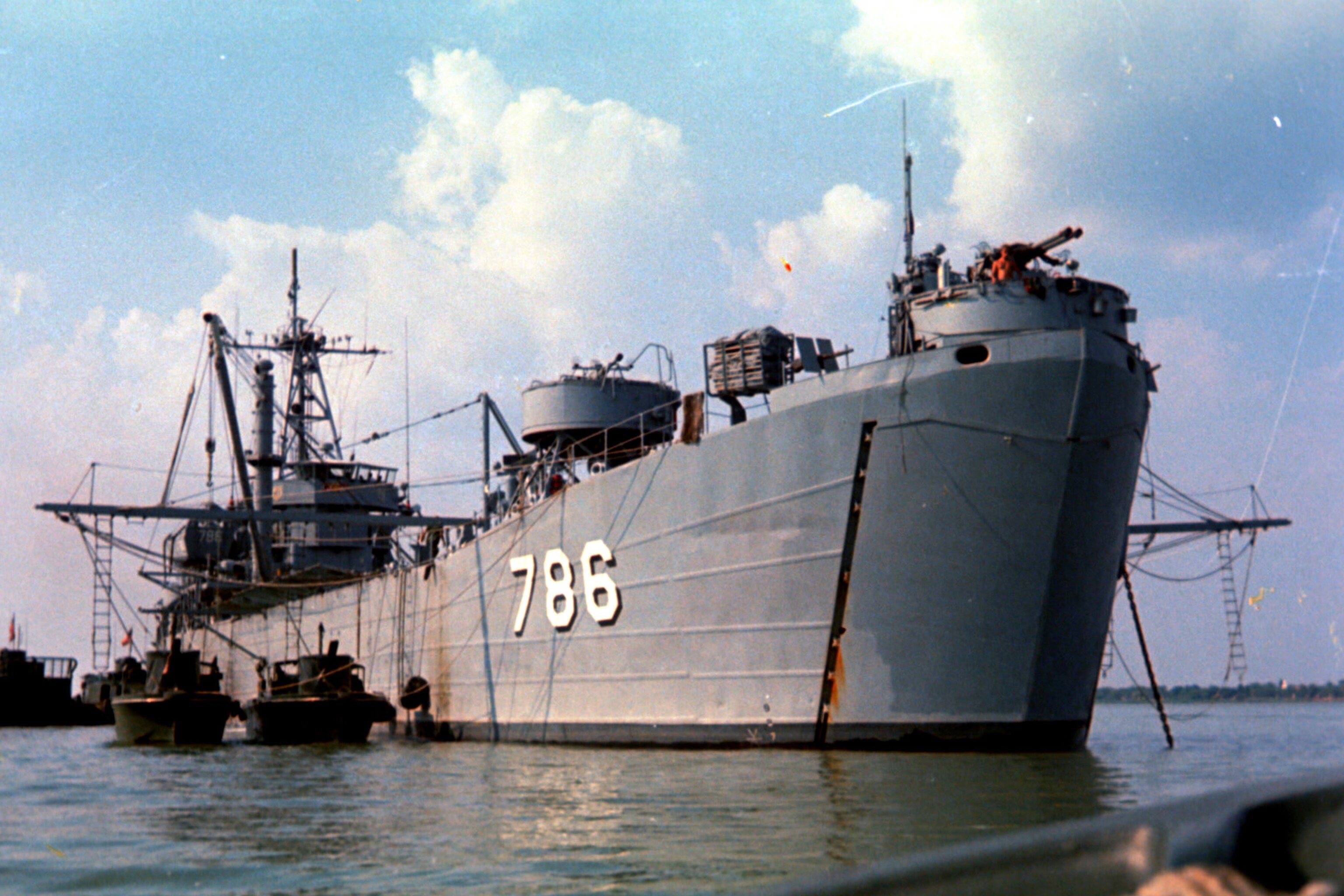

I had just dropped off to sleep when I was suddenly awakened by the boatswain of the watch. “Chief White. Wake up! They blew up Song Ong Doc! They need you and Doctor Bunin right away.” It was just after 11:00 p.m. and I had been asleep an hour. Song Ong Doc was home for a small U.S. Army Special Forces Base and a U.S. Navy River Boat Squadron. The area was a known Viet Cong stronghold on the Gulf of Thailand and our squadron provided gunfire support for the military forces and medical and civil  assistance for the civilians. The USS Garrett County was a [formerly Coast Guard-manned World War II-era] LST that provided the area with supplies and assistance. I felt sorry for the troops still in country—they would have to fight their way out. There was only one way to escape—that was by boat. The Viet Cong gave us advance notice that they were going to blow up the base; I just didn’t think it was going to be this soon.

assistance for the civilians. The USS Garrett County was a [formerly Coast Guard-manned World War II-era] LST that provided the area with supplies and assistance. I felt sorry for the troops still in country—they would have to fight their way out. There was only one way to escape—that was by boat. The Viet Cong gave us advance notice that they were going to blow up the base; I just didn’t think it was going to be this soon.

Lower Away

I grabbed my medical bag and headed for the 1st deck to catch a ride to the LST where all the action was going on. Doctor Bunin was there already and charged up to go. He was against the war in general, but a very good doctor. He saw no sense in all the trauma war brings. I learned a lot from him and would put that knowledge to use many times tonight. Our 26-foot motor surfboat was hanging over the side waiting for the word to be lowered. It was pitch dark, but in the distance you could see fires burning in the village—they must be catching hell. We had just got underway when two U.S. Air Force jets came over our boat, which was painted gray, and shined a bright  strobe on us. I was scared as hell of Air Force planes; I knew the damage they could do. Someone must have told them we were friendlies. They buzzed us very low; the sound of the jets was deafening and you could feel the heat and smell the fuel from their exhaust as they roared away. All at once everything turned dark and quiet again—just the sound of ur engine and some small waves hitting the bow of the boat. It’s exciting when fighter jets buzz you; a real sense of their power. I don’t need any trouble from friendly fire.

strobe on us. I was scared as hell of Air Force planes; I knew the damage they could do. Someone must have told them we were friendlies. They buzzed us very low; the sound of the jets was deafening and you could feel the heat and smell the fuel from their exhaust as they roared away. All at once everything turned dark and quiet again—just the sound of ur engine and some small waves hitting the bow of the boat. It’s exciting when fighter jets buzz you; a real sense of their power. I don’t need any trouble from friendly fire.

Dead Ahead

Nothing could have prepared me for what lay ahead. I had training with the U.S. Navy Training Command at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (GITMO), and Pearl Harbor for this type of evolution. I never believed I would be involved in a situation of mass casualties of this magnitude. This was a Navy war—I was Coast Guard. Things had changed; we were part of the Coast Guard Squadron Three out of Subic Bay, Republic of the Philippines, and under operational control of the U.S. Navy. Our mission was to train Vietnamese sailors to take over our ship and provide gunfire support for their troops. As we approached the Garrett County, an LCM from Song Ong Doc with a load of wounded passed us and were flying a yellow flag with large black letters that said “Fuck it.” I guess they had it. There was plenty of action on the Garrett County—sailors were running all over the deck. They were taking wounded off the [helicopter] gunship; other sailors were putting stabilized wounded on the same gunship for transfer to a better-equipped medical facility. Doc Bunin and myself headed toward the Ward Room, which was Primary Battle Dressing Station (BDS). It was easy—all we had to do was follow the decal signs to the BDS, which were on the gray bulkheads. Petty Officer Evans was the corpsman on the LST and an old friend of mine from U.S. Navy Independent School. We could work together very smoothly; I was glad he was here.

BDS

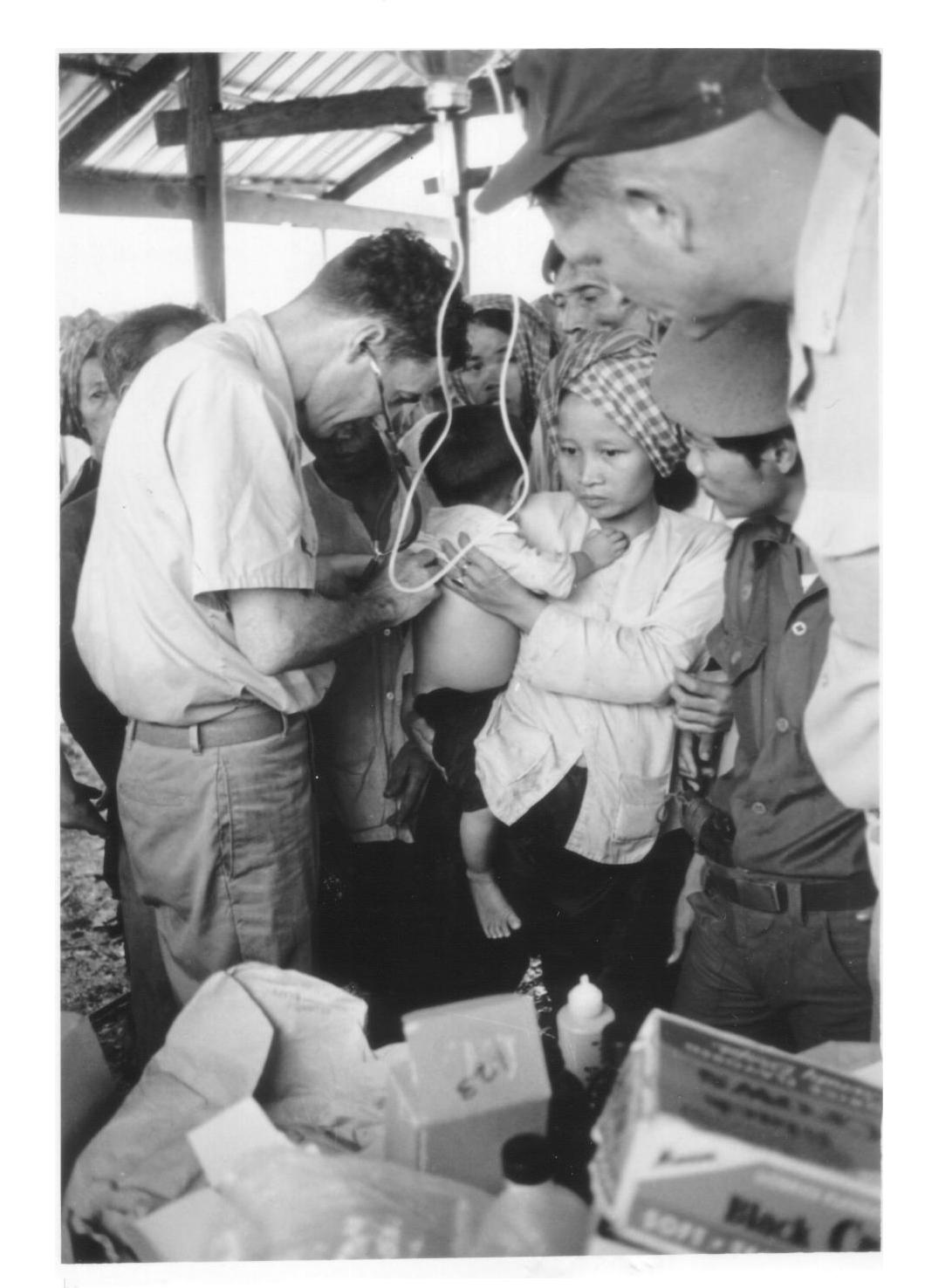

Evans would be the circulating corpsman tonight. It was his ship and he knew where all the supplies and equipment were located. I knew he would be a good backup when we got into a jam. The crew helped us strip down two large tables to serve as our operating room tables. The OR [operating room] lights were permanently mounted for this type of emergency; Evans had all the packs laid out and we were ready to go. Doc Bunin started working on a kid right away. There were so many wounded civilians—mostly kids—I didn’t know where to start. The crying and moaning worked on you for a while. You could only do so much at one time. The Ward Room started to pick-up the village smell—part diet, part war. I recognized it and put it out of my mind—there was work to be done. I picked up a kid who was close by and started the first of many procedures. Everything we learned at GITMO and Pearl started to fall into place. I’ll never bitch about Underway Training again.

Morgue

The Chief’s Head would be the morgue; the Crew’s Mess was the triage center; and the Officer’s Head was for the seriously wounded. Evans had this all arranged before we arrived; it saved a lot of time and helped the patients’ outlook.

Operating Room

Just the two of us to work on the wounded. I knew we weren’t going to be able to save them all—there were too many and more on the way. Off in a corner were about eight Navy men from t he 572nd River Boat Squadron—all were wounded and sitting there stripped to the waist. Some of the sailors were watching trickles of blood leaking from their bodies. One man had a large stomach wound, but refused treatment until the kids were taken care of properly. He said “They were worse off than he was.” It was true. The kids were dying on us quicker than we could treat them. I recognized some of them from the village where they would play with the hair on my arms. Now I was looking at the shiny sockets where their arms and legs belonged. What the hell could have done this? A Navy man came over, looked at the wounds and said “The gunship did all the damage.” The Viet Cong would come into the village, throw a few hand grenades and disappear. The villagers would run through the elephant grass to hide; the gunship would come over and illuminate the area; seeing the grass move and thinking it was the Viet Cong, it would open fire. The kids and civilians got hit all the time.

he 572nd River Boat Squadron—all were wounded and sitting there stripped to the waist. Some of the sailors were watching trickles of blood leaking from their bodies. One man had a large stomach wound, but refused treatment until the kids were taken care of properly. He said “They were worse off than he was.” It was true. The kids were dying on us quicker than we could treat them. I recognized some of them from the village where they would play with the hair on my arms. Now I was looking at the shiny sockets where their arms and legs belonged. What the hell could have done this? A Navy man came over, looked at the wounds and said “The gunship did all the damage.” The Viet Cong would come into the village, throw a few hand grenades and disappear. The villagers would run through the elephant grass to hide; the gunship would come over and illuminate the area; seeing the grass move and thinking it was the Viet Cong, it would open fire. The kids and civilians got hit all the time.

More Wounded En Route

The casualties kept arriving all night long. A lot of parents were in the Crew’s Mess scared and crying. They were waiting for their kids to come out of our OR. I don’t know who told them the bad news. It wasn’t us. At times, we had two and three kids on the table at the same time. They didn’t take up much space when their legs were missing. One little girl who I knew very well was on my table with her left arm and both legs blown of their sockets. I knew I was losing her; she was in shock, turning gray. I did a tracheotomy on her and attempted to ventilate her. Doc Bunin came over and said “She should have made it.” He turned her over and found a deep head would which swallowed his forceps. Now I knew what killed her. Ordinarily, I would have picked it up [when] doing a body survey, but they were coming so fast and had so many wounds, you threw the book away in some cases. We did our best to stabilize them for transportation to a better-equipped facility.

After Shock

It was 4:00 a.m. and we had a short break and caught up for a while. I felt so bad for the little girl that I knew and lost that I went to the Chief’s Head and brought her back and started cleaning her up. Doc Bunin and myself loosely sewed her limbs back in place and bandaged her wounds so her mother didn’t see the horrors her daughter went through before she died. I wish I could have cried; it might have helped, but I was cried out. More wounded were coming, but in smaller groups now. I took a quick head break and could barely get into the compartment because of all the dead blocking the door. You keep looking at them--maybe they’re not all dead, maybe one was in shock and was now breathing on their own. It just didn’t happen. They were all dead.

Normal Routine

It’s 6:00 a.m. – we were finally finished taking care of the wounded from last night’s attack, but there would be more nights like this. I said goodbye to Evans—he really helped us with all his preparation and knowledge. Doc Bunin and myself went back to our ship; we had sic k call for our crew at 8:30 a.m. What a way to fight a war—kill all the kids and the next day is routine as usual.

k call for our crew at 8:30 a.m. What a way to fight a war—kill all the kids and the next day is routine as usual.

Compassion

You usually don’t hear many stories about our military helping the Vietnamese civilians and it happened all the time. A good piece of history was the Navy men who gave up their beds, food, and ship to help the wounded civilians. We took over their ship for the night and the crew volunteered to help us in any capacity. The wounded men who refused treatment until the kids were taken care of has a lot to say about the compassion of our young warriors.

No Purple Hearts

Later that night, the U.S. Navy Command called our ship to verify that a doctor had treated the wounded Navy men. I couldn’t find Doc Bunin and told the Navy “a doctor treated them all.” At the same time, Doc Bunin came into the radio room and got hold of the microphone and told the commander that Chief White treated half of the wounded. The Navy had some regulation that a doctor had to treat your wound to earn a Purple Heart [Medal]. These men deserved more than a Purple Heart.

Doc White’s Conclusion

The night on the Garrett County changed me. I never got close to the village kids after that night. We saved a lot of people that night and the crew of the USS Garrett County made the difference with their compassion and spirit. I do hope to see Evans someday as a Chief Petty Officer—he deserved it.