Jan. 14, 2022 —

[This essay is adapted from the non-fiction book chapter “Men against the Sea,” Sea, Surf and Hell: The U.S. Coast Guard in World War II (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1945), 72-78.]

The Coast Guard patrol craft Wilcox was lost off the Mid-Atlantic coast Sept. 30, 1943. The following account is taken from the statement made by its commanding officer, Lt. Elliott Smyzer, a few hours after his rescue.

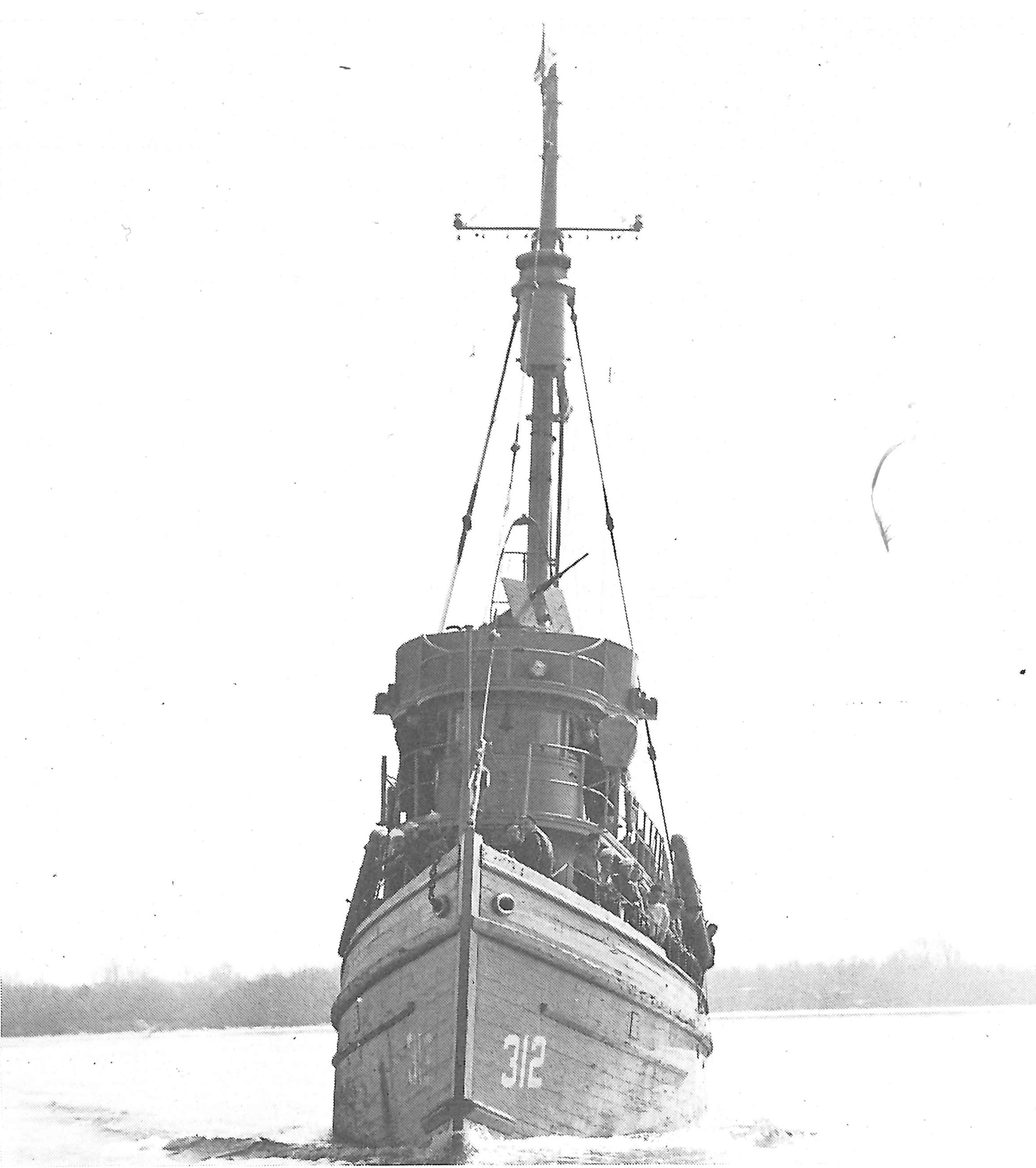

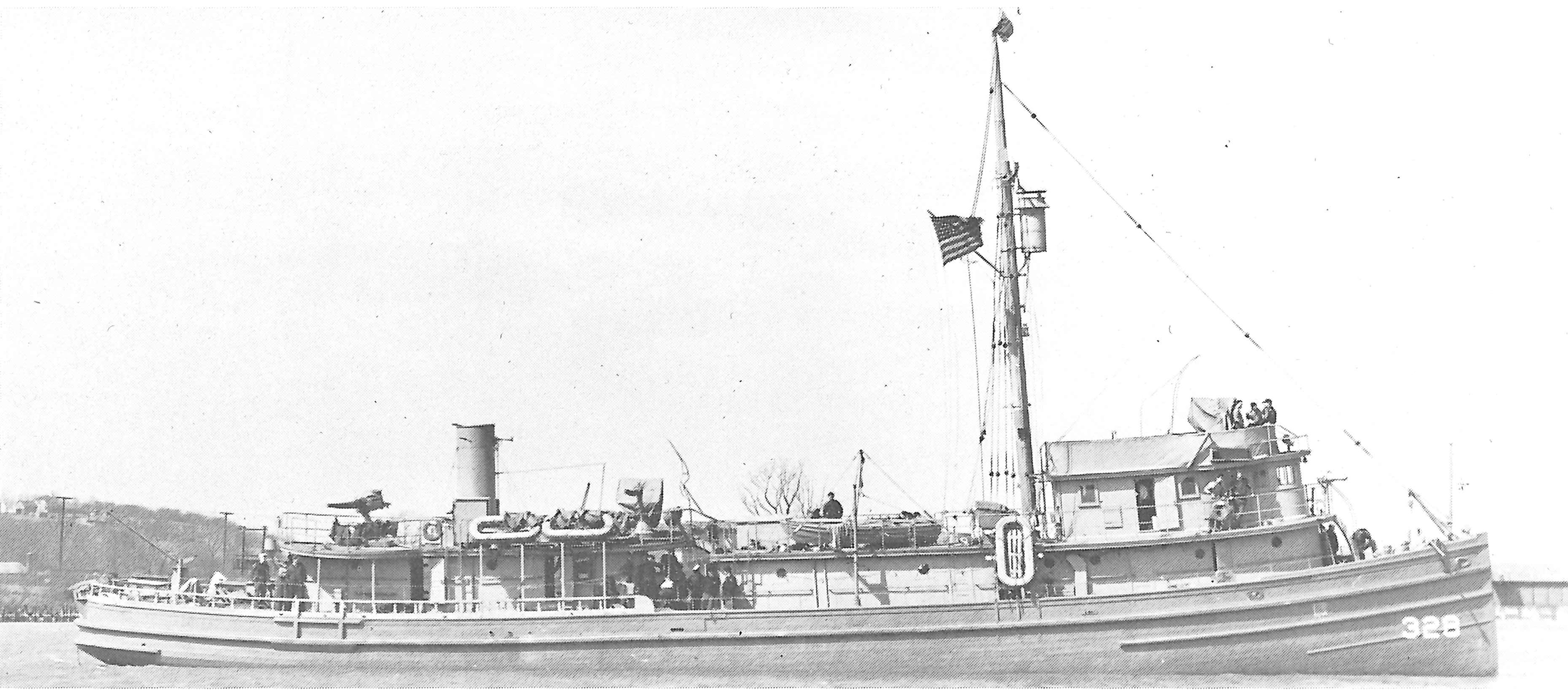

My ship had formerly been a Menhaden fishing vessel and was converted from that into a vessel to be used for patrol.

We departed in September 1943 from an East Coast port. Going down the bay, the engine room department had some slight difficulty with the engine and asked to stop and make necessary repairs.

The engine room called the bridge a short time later and told me they were ready to proceed.

We headed out with a following sea and increasing winds. I thought that with the following seas we would be all right. As the sea and wind increased in velocity, I found that we were rolling very badly, sometimes as much as 30 degrees.

As darkness approached, we continued a long the same course. We were forced to stop two or three times for the engine room again and, in stopping, I tried to take in calculations and in that way figure where we were.

long the same course. We were forced to stop two or three times for the engine room again and, in stopping, I tried to take in calculations and in that way figure where we were.

Toward morning, I received word from the engine room that they would have to stop because something had gone wrong with the main bilge pump. While we were stopped, we rolled almost as much as 75 degrees. It seemed as if we must surely go over, but [the vessel] righted [it]self and I knew that if [it] didn’t go over in seas like that [it] would stay afloat.

Sometime between 4:30 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., the engine room officer came up and said he was having serious trouble. I asked to what extent, and he said, “Bad, but if I can get my auxiliary bilge pump going we will be able to hold our own,” and I said, “OK.” He went back to the engine room and called up and said the auxiliary pump would be all right. Apparently, something else went wrong, because he called up a short time later and said, “Captain, we have got to get to port; something has gone wrong and we are taking in water so fast that I cannot keep ahead of it. Can we put into port somewhere along here?”

I knew that there was no port we could reach, but I thought if we changed our course and headed directly to the beach the waves would not be so severe when we got in far enough; and we could swing the ship around, just keeping enough headway on [the vessel] so that we wouldn’t be beached. I didn’t want to run up on any rocks, and I didn’t know precisely what the condition of the beach along there was.

I called my first class radioman. He said, “Skipper, are you going to send an S.O.S.?” I said, “Yes.” He and I stood at our chart table writing out the message. As we were doing so, the lights went out and word came up from the engine room that our last generator had stopped. We immediately hooked up our portable set. Our radio operator sat at that set for the next hour, sending out messages asking for help, but apparently it was not picked up by anyone. My engineer came up to the bridge and said, “Things are in pretty bad shape, Captain; I have started a bucket brigade. I think we are probably good for four hours.” I said, “If we are good for four hours we can reach the beach.” But a short time later, we were forced to slow down again; then we stopped because the main engine had failed again.

We started again and steamed along on a course due west. I tried a course of northwest, but the seas were so great along that course that I changed to a due westerly course on my magnetic compass. My engineer came up to the bridge again and said, “Captain, every wave we take aboard is just flooding us out.” I said, “Yes, I know.”

Shortly after 8:00 a.m., Sept. 30, a cry went out, “Man overboard!”

I guess the man was pretty well up forward when we suddenly dived into a terrific sea that swept over the entire superstructure and washed him over the side. I immediately stopped my engines and threw him a life ring.

It was a cruel decision that faced me. Being stopped as we were, the seas broke over us with greater force and fury than when we were under power. I had 34 enlisted men and three other officers aboard to think of. If I tried to swing my ship in those seas, [it] would go over and I would lose everybody. The wind was blowing about too much for a ship of this size. I decided to proceed toward the beach. We were turning somewhere between 250 and 300 revolutions per minute. Later on, my engineer said he could give me 350 revolutions per minute again, which was our normal speed. I said, “Give it to me by all means so we can get this thing in somewhere.” But our speed didn’t last long. At about 8:30 a.m., our main engine stopped. We were not able to get them going again, but we kept the ship heading in a general westerly direction. At the same time, we had a southwest wind blowing us in a northeasterly direction.

I decided against abandoning ship because I knew no one could live on a raft in such seas as we were running at that time. I passed word around the ship that we would immediately start a bucket brigade and keep it going as long as was humanly possible. The engine room was taking all the water, apparently coming in from the lazarette. As time went on, the plank seams along the side of the wooden ship in the engine room began to let water in; the beating of the seas was washing out the caulking between the planks.

The bucket brigade worked very well until, all of a sudden, someone shouted out, “Ship off stern.” It looked as though he was headed directly for us. My first thought was that he was the one to receive our S.O.S. As he approached, he changed course, went over a ways to our port, and then changed course again to run apparently parallel to the position to which our ship was lying. I had a distress signal hoisted. We fired off rockets. We fired our 20-millimeter [gun], the magazines of which contained quite a few tracers, which could be seen. We were not able to use our big blinker because the power was gone, but we had a portable blinker that we got up to topside and my quartermaster signaled him and got a reply. We explained to him the precarious position, which we were in and asked for help. He lay to for a few minutes but my quartermaster reported to me that he could not get a definite signal out of him; in other words, we were not sure that he understood us. Sad to state, he very shortly proceeded on his course and was soon lost over the horizon.

The morale of my crew dropped to nothing. I heard remarks such as, “What’s the use, we are licked.”

I called everybody up to the topside; I crowded as many into the room as I could and the rest stood out on deck. I said,

“Boys, we are not going to give up hope. You are all cold and wet the same as I am, but you must have faith. We are going to pull through this. You are going to do exactly as I tell you. It will be tough, but we are going to fight this thing out until the seas go down to such an extent that I feel it will be comparatively safe for you to ride the rafts. Not one man goes over the side on a raft until I give the word.”

Our galley fire had been out since the day before and we could not make coffee. We could not get fresh water to drink because we had no power to pump it, and I realized that for men working as they were going to have to work, it was going to be pretty tough without water.

Nevertheless, I called my two junior officers up and said, “I want you to organize a bucket brigade and split it up into two watches. As soon as one watch is relieved, let them turn into their bunks. A half hour watch will be sufficient, but when the half hour is up get them back to their work immediately.”

The boys did just exactly as ordered. They were sick from lack of proper food and rough seas. Every once in a while, I could see one of them dash to the rail to get the necessary relief, but he would pop right back to the job as soon as he finished. No skipper was ever blessed with a better crew.

Every once in a while, somebody would say, “I’m terribly tired, Skipper.” I would make some such reply as, “It doesn’t make any difference how tired you are. We are going to keep this ship afloat until it is impossible to carry on longer.” At 10:20 p.m., the seas were breaking over the stern. The water was gaining on us. I could feel that we were rapidly developing a terrific port list, so I passed the word for everybody to clear out of the engine room and stand by their raft, but no raft was to go over the side until I gave the word. Every man was in a life preserver all day long. When everybody on the port side was at their raft, I gave the word to lower away, get on their rafts, and get away from the ship as quickly as they could. This was about 10:30 p.m.

When the port rafts were on their way from the ship, I got myself around on the starboard side. When I had determined that everyone was at his raft, I gave the word for them to lower away.

They had just begun to pull away from the side of the ship when I saw my chief engineer still aboard. I thought that he had gone on one of the rafts. We climbed to the topside where our dinghy was secured and were going to lift it out of its cradle and slide it over the port side. Apparently, though, while I had made it loose during the afternoon and placed my sextant, chronometer, logbooks, and everything else inside, somebody had tied it up again. We were unable to get the boat loose.

“Get over the side as fast as you can,” I told the chief engineer. “In another minute [it’s] going down.” I got him over the side and I was the last man aboard ship. When l saw that he was safely over, I climbed down myself.

I had a terrible time getting away from the ship because the suction was tremendous, but I fought my way around the stern. In the distance, I could see a string of life rafts; I had previously passed the word to have the three life rafts on the port side tied together so they would stay together.

I tried to swim fast enough to catch up with the rafts and, in doing so, my shoulder brushed against a ladder about three and one-half feet long and two feet wide. I climbed upon the ladder and it was much easier for me to float that way. I tried to paddle with my hands but I found that I was losing ground and was not able to make as much headway toward the rafts as I could by swimming, so I got off the ladder and started to swim for the rafts. I still couldn’t make much headway. I’d injured my left arm during a terrific roll that day and it seemed that it had no strength. However, I swam until I became exhausted and finally tried just to keep afloat. In a short time, I found the ladder back again. I decided it must be there for a purpose and climbed on it. The last time I saw my ship the mast was parallel with the sea.

Due to the smallness of the ladder, I had a hard time clinging to it. Sometimes it would float along for what seemed quite a spell, and then perhaps I’d lose my balance and roll into the sea again. I spent 17 hours fighting with that ladder.  My men spent the same amount of time on their rafts. The only advantage they had over me was that they had fresh water and sea rations.

My men spent the same amount of time on their rafts. The only advantage they had over me was that they had fresh water and sea rations.

Sometime the following afternoon, and in there I seemed to have lost track of time, I heard rockets going up and could hear somebody talking loudly. I tried to hold myself up high enough in the water to see. I could hear the report and see the rockets in the air, and then I heard a motor.

Looking around I saw a blimp and, in the distance when the sea would wash me up high enough, I could see the outline of some ships. I don’t know how many there were, but I noticed one coming in my general direction. The blimp passed over and I don’t believe he saw me. The ship saw me, however, and came over and picked me up.

Later they transferred me to the ship that had picked up all of my men, and I was told that my crew breathed a prayer of relief when they knew I’d been saved.

All my crew was accounted for except the man who fell over the side, whom I was unable to save without the risk of losing the entire crew.

In the final analysis, I can only say that every officer and man board the ship did everything possible. There was not one single man who shirked his duty. I can thank God that I was able to bring my crew, with the help of the ships that picked us up, to safety once more.