Dec. 31, 2021 —

Of all the lifesaving statio

Of all the lifesaving statio ns in Coast Guard history, by far the most remote station was located at Nome, Alaska, on the northern Bering Sea coastline. The Life-Saving Service station at Nome was in operation from 1905 to 1947 and its isolation resulted in a unique history.

ns in Coast Guard history, by far the most remote station was located at Nome, Alaska, on the northern Bering Sea coastline. The Life-Saving Service station at Nome was in operation from 1905 to 1947 and its isolation resulted in a unique history.

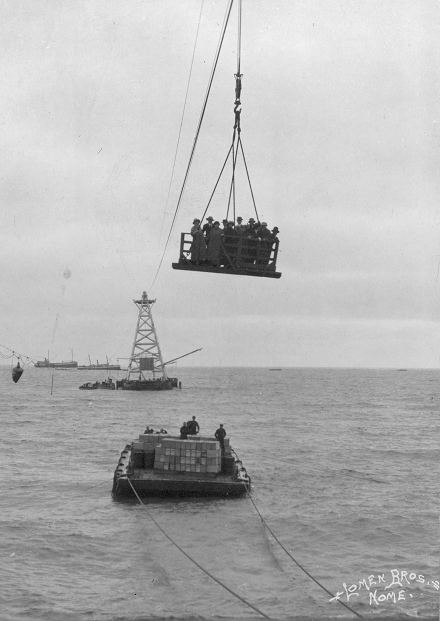

Established in the summer of 1899, the coastal town of Nome was the region’s entry and logistics site for thousands of gold miners who arrived by ship. Nome had no harbor, only the shallow Snake River inlet with a small mooring basin. This left Nome’s beachfront exposed to winds and seas coming off the Bering Sea. Due to its proximity to the Arctic Circle, Nome had a very short shipping season—usually from June to October. Moreover, except for one telegraph line to Anchorage, it was not until World War I and the introduction of wireless radio, that Nome had wintertime communications with the outside world.

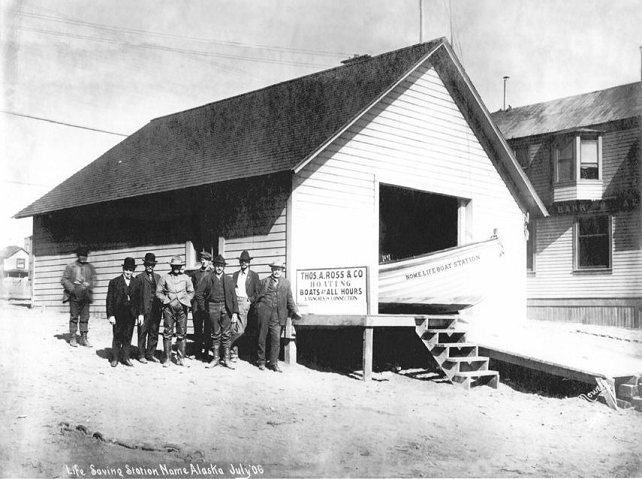

When Station  Nome commenced operations in 1905, Thomas A. Ross was selected as keeper. A former merchant mariner from San Francisco and owner of a Nome boat shuttle

Nome commenced operations in 1905, Thomas A. Ross was selected as keeper. A former merchant mariner from San Francisco and owner of a Nome boat shuttle service, Ross had no lifesaving experience. The reason for his appointment was likely due to his knowledge of the Seward Peninsula and local sea conditions. Unlike the station’s crew, Ross had his own house in town and lived with his family.

service, Ross had no lifesaving experience. The reason for his appointment was likely due to his knowledge of the Seward Peninsula and local sea conditions. Unlike the station’s crew, Ross had his own house in town and lived with his family.

Operations took place during ice-free months, when Nome was open to navigation, but the open water season for Station Nome was relatively short. During winter months, when the Bering Sea and beachfront were iced over, the station functioned as a Federal Government auxiliary service. It was the service’s only station equipped with a dogsled providing assistance with local ice rescue, firefighting and support for the Native Alaskan population.

Station Nome was located at the end of a very long supply line. It took years before service supplies of uniforms, paper forms, logbooks and rescue equipment were readily available to the station. In addition, payroll checks for the crew were often delayed for months due to the thousands of miles separating Nome and the Seattle district office. Delays continued until federal paychecks could be issued locally without the need to mail them from Seattle.

In Nome, there were no local fishermen or boatmen to recruit, so finding suitable surfmen proved challenging. Retaining surfmen was also difficult given the nearby goldfields and lucrative gold mining jobs. Station Nome had the highest turnover rate of any U.S. Life-Saving Service Station. Most of the station’s surfmen changed each year, especially during the summer months when ships were available for passage out of Alaska.

Most of Station Nome’s rescue cases involved small craft foundering in beach surf. On occasion, the station provided assistance with unique cases. These included Arctic expeditions, such as famed Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen’s expedition in the vessel Gjoa,  which drifted across the Northwest Passage from the At

which drifted across the Northwest Passage from the At lantic Ocean to the Bering Sea, as well as the first cross-Arctic aircraft flights of the 1920s and 1930s.

lantic Ocean to the Bering Sea, as well as the first cross-Arctic aircraft flights of the 1920s and 1930s.

The most dramatic rescue performed by Station Nome occurred on July 7, 1906, during a violent storm. The Motor Schooner Greyhound had anchored off the beach and the captain left one crewmember aboard. As conditions worsened, the crewmember signaled that the vessel was dragging anchor toward shore. Seeing the signal, Keeper Ross and his crew launched a surfboat and rowed to the ship through heavy surf. Pulling alongside, they rescued the Greyhound’s crewmember and safely returned to shore. After the rescue, the station crew secured the grounded Greyhound, allowing the schooner to be refloated after the storm.

The entire Nome beachfront, including that in front of the lifesaving station, was vulnerable to storms, high winds, heavy seas, and pack ice piling up on the beach. For example, on Oct. 6, 1913, a severe Bering Sea storm destroyed the station’s boathouse, although the boats and equipment were saved. In the summer of 1914, a new and expanded boathouse with a lookout tower was built as a replacement.

In the fall of 1918, during the Spanish Flu Pandemic, a serious outbreak occurred in Nome. Between October and November, the entire station crew contracted the disease. As one surfman recovered, he would care for the next who fell sick, however, Surfman Martin Andersen did succumb on Nov. 6. By Nov. 10, most of the crew had recovered and, in mid-November, they established a temporary hospital to serve local Alaskan natives, who were unable to use Nome’s overwhelmed hospital.

Station Nome not only saved lives at se a, it saved Native Alaskan lives on land. During the pandemic, Surfman Levi Ashton volunteered to establish a Native Alaskan treatment facility at Cape Prince of Wales. Using the station’s dogsled, he travelled 160 miles up the coast from Nome in the dead of winter to complete the mission. Station Nome was provided with its own dogsled team and equipment for local use. In March 1919, after he returned from his successful dogsled mission, Ashton was disabled by severe flu symptoms. He had to be evacuated to a marine hospital in the Seattle area and was honorably discharged due to poor health.

a, it saved Native Alaskan lives on land. During the pandemic, Surfman Levi Ashton volunteered to establish a Native Alaskan treatment facility at Cape Prince of Wales. Using the station’s dogsled, he travelled 160 miles up the coast from Nome in the dead of winter to complete the mission. Station Nome was provided with its own dogsled team and equipment for local use. In March 1919, after he returned from his successful dogsled mission, Ashton was disabled by severe flu symptoms. He had to be evacuated to a marine hospital in the Seattle area and was honorably discharged due to poor health.

Throughout its existence, Station Nome’s surfmen maintained a close association with the local Alaskan native population. The station assisted Native Alaskans in searching for and recovering missing hunters, fishermen or children. In addition, the wife of one-time officer-in-charge, Chief Petty Officer Kurt Sprenger, was one of the Bureau of Indian Affairs nurses assigned to Nome, who provided medical services for Native Alaskans.

Nearly all the buildings in Nome were of wooden construction. Even the city streets had wooden planks laid in the ground. These planks facilitated travel during the winter months and in the warmer months when the permafrost ground thawed and turned to mud. Given the dry winter conditions and prevalence of wood, destruction by fire was a constant threat, especially with Nome’s lack of firefighting equipment and trained crews.

On Sept. 17, 1934, a fire started in Nome’s Golden Gate Hotel. Located in the center of town, not far from the lifesaving station, the hotel was built of wood like the rest of Nome’s buildings. With high winds fanning the fire, the conflagration spread to other buildings, overwhelmed firefighting resources, and raged out of control. Fortunately, there were only two deaths among thousands of residents. All of the station’s boats and most of its equipment were saved, but the station house and barracks were destroyed.

The 1934 fire also destroyed most of Nome’s commercial buildings, local food supplies, and nearly all the homes in town. With the start of the Arctic winter season only a month away, m ost of the town’s residents had to evacuate to southern Alaska, or even to the lower 48 states. A fleet of ships, including the new Coast Guard Cutter Northland, received orders to help evacuate the city.

ost of the town’s residents had to evacuate to southern Alaska, or even to the lower 48 states. A fleet of ships, including the new Coast Guard Cutter Northland, received orders to help evacuate the city.

Although all the boats and most of the other rescue equipment were stored or staged at the Snake River Inlet, the loss of the Station Nome’s boathouse and barracks to fire rendered it inoperative. In November 1934, Keeper Ross, now a chief warr ant officer, along with his wife and daughter, boarded the last ship to Seattle before the navigation season closed. Some of the station crew also evacuated with their families, leaving a small three-man detachment of one petty officer and two surfmen in Nome. Although Ross returned in June 1935 for the summer season, he departed in October and never returned.

ant officer, along with his wife and daughter, boarded the last ship to Seattle before the navigation season closed. Some of the station crew also evacuated with their families, leaving a small three-man detachment of one petty officer and two surfmen in Nome. Although Ross returned in June 1935 for the summer season, he departed in October and never returned.

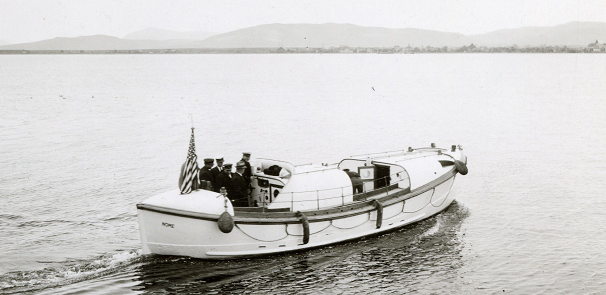

For the next 10 years, the remaining station crew of three men lived in private quarters in town and conducted station operations out of the surviving Bureau of Indian Affairs’ schoolhouse. While a new motor surfboat and motor lifeboat were kept moored along the Snake River just inside the inlet, the pulling surfboats were no longer used. During the winter months, all boats were hauled out and stored ashore under cover.

During its final years, Station Nome served primarily as a search and rescue detachment. The gold deposits had been exhausted and Nome lost its importance in shipping and transportation. The station’s small unit of a petty officer first class or chief petty officer, and one or two surfmen saw less need of their services. After World War II, there seemed little need to maintain Station Nome and it closed in 1947.