Aug. 26, 2022 —

Coast Guard Seadog Sinbad

Coast Guard Seadog Sinbad

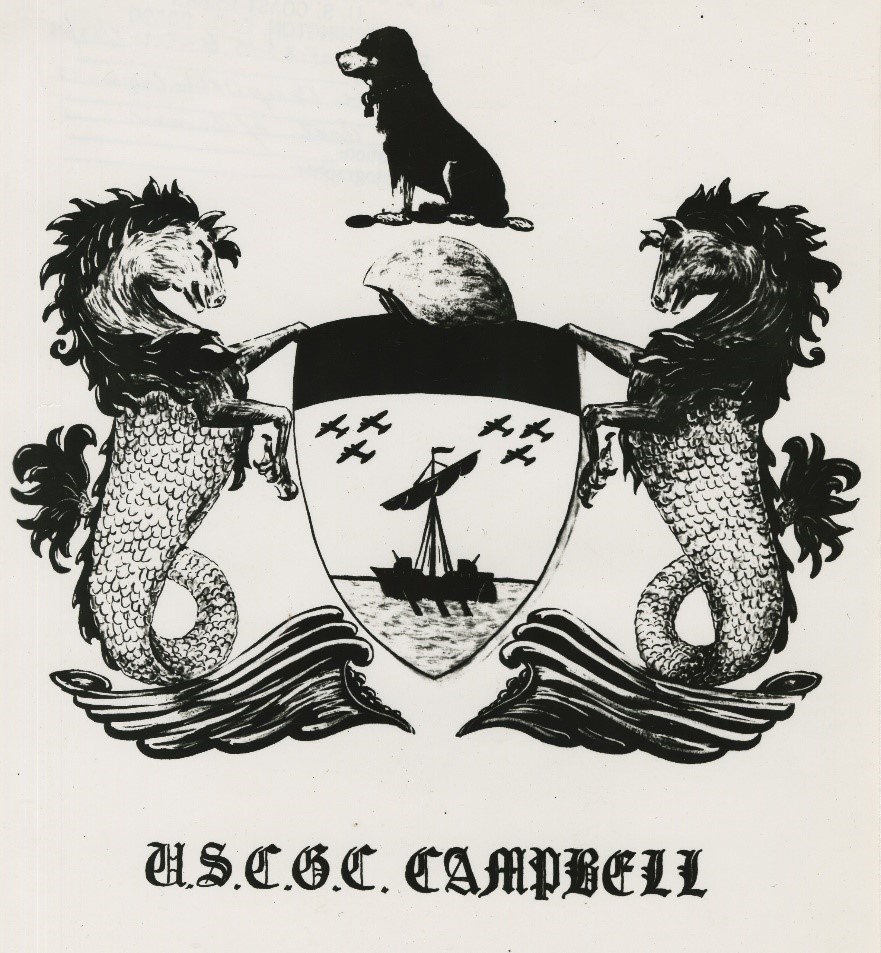

At the United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office, there are many hidden gems in its Special Collections. There is a large collection of World War II ephemera, including scrapbooks, photographs, diaries, and correspondence. The Papers of Sinbad provide a rather humorous look into the service of World War II’s most famous Coast Guardsman aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Campbell (WPG-32). Every single Coast Guard member who served alongside Sinbad found him extremely likeable and impossible to forget, even in the midst of ferocious sea battles. After all, Sinbad was Campbell’s mascot—a dog.

Coast Guard Cutter Campbell

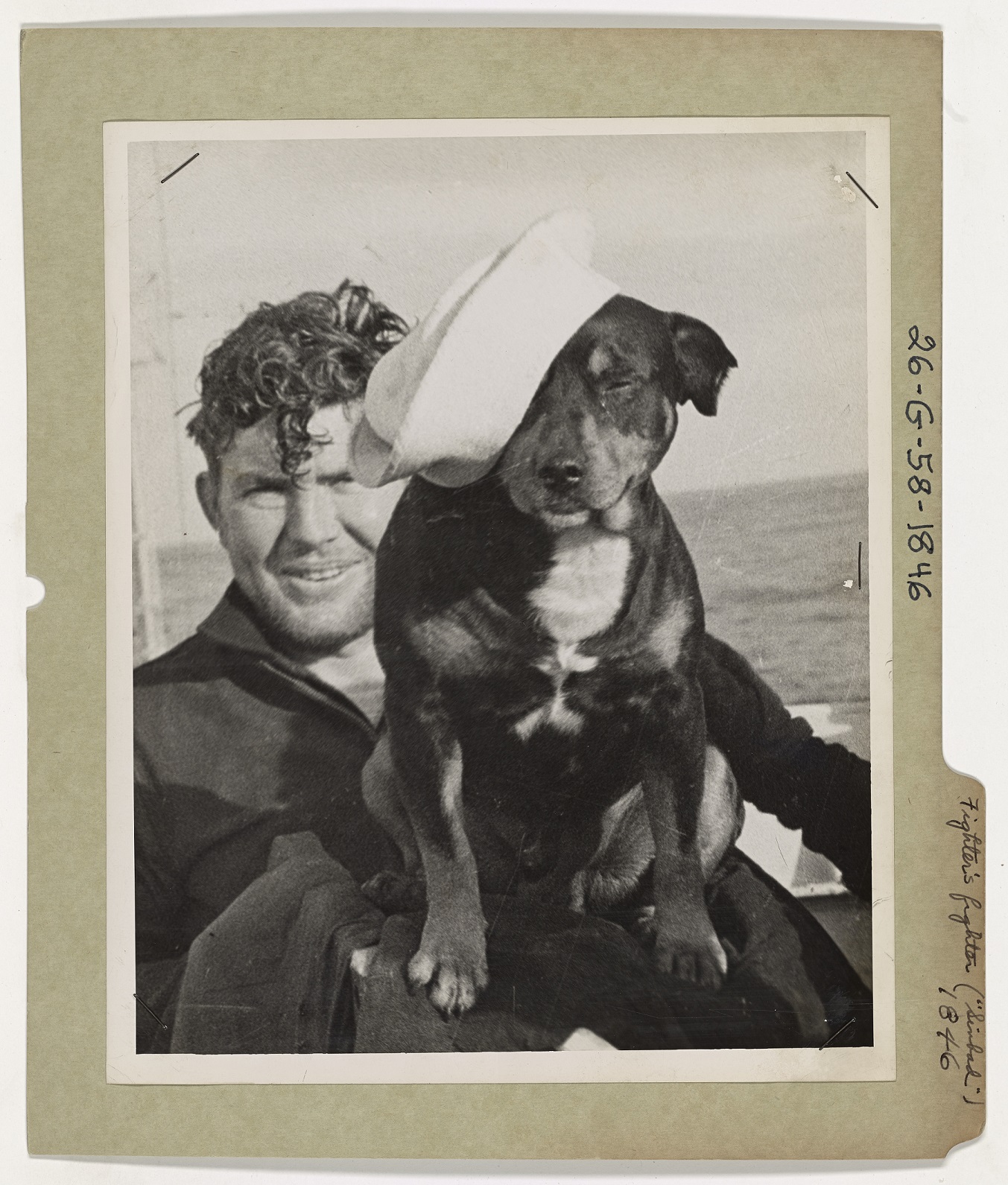

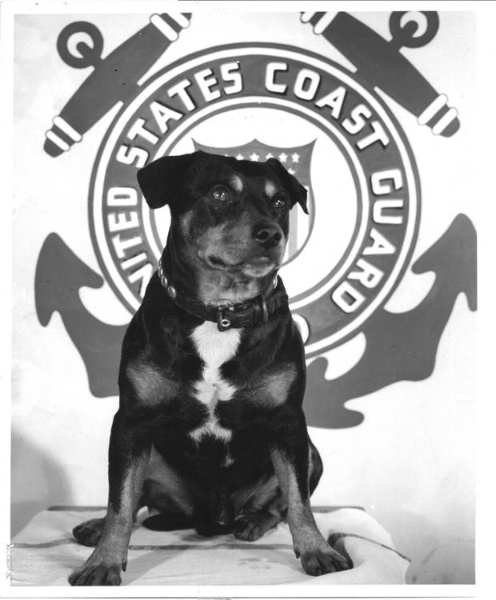

Campbell’s crew plucked Sinbad off the streets of Staten Island, New York, in 1937. A 24-pound mixed terrier, Sinbad was smuggled aboard in a liberty bag. He interrupted roll call the next morning by insisting very loudly that he was present. Amused, Campbell’s commanding officer, Capt. James Hirshfield, asked what was going on. A crewmember piped up, “Excuse me, sir. That is Sinbad, our new mascot. That is, sir, the dog was brought aboard last night, too late before sailing time for your permission to be secured. It was our intention to ask you, sir, but the opportunity did not come.” In the midst of this explanation, Sinbad planted himself squarely at Hirshfield’s feet and began vocalizing his excitement and wagging his tail furiously. “All right, Sinbad, you’re our mascot. You’ve just about broken up the muster, so we’ll let the men go. Let’s hope you enjoy your stay aboard,” Hirshfeld said.

Life aboard Campbell

Life aboard Campbell

Sinbad appeared at every roll call with his lifejacket in his mouth, dropping it to bark when his name was called. He had his own custom-made hammock and collars,  which were made from rope on board the cutter. The crew made him his own uniform, much to Sinbad’s dislike. After standing inspection in uniform one day, he went below decks and ripped it off. He never wore a uniform again for the remainder of his service. Sinbad had the run of Campbell, climbing ladders on his own and taking hot showers half a dozen times a day (but avoided at all costs cold water). At nine o’clock each evening, Sinbad tugged on the radio operator’s leg and sat on his haunches, signaling it was bedtime. His life jacket was also his bed, and, each night, he chose a different crewmember as his bunkmate. He avoided officer wardrooms and quarters and rarely associated with officers on liberty. Sinbad was so loved by his fellow Coast Guardsmen that he had his own service number, “069-069,” and his own service and health records. A 1940 Christmas dinner program in the collection lists the names of Campbell’s crew—including Sinbad.

which were made from rope on board the cutter. The crew made him his own uniform, much to Sinbad’s dislike. After standing inspection in uniform one day, he went below decks and ripped it off. He never wore a uniform again for the remainder of his service. Sinbad had the run of Campbell, climbing ladders on his own and taking hot showers half a dozen times a day (but avoided at all costs cold water). At nine o’clock each evening, Sinbad tugged on the radio operator’s leg and sat on his haunches, signaling it was bedtime. His life jacket was also his bed, and, each night, he chose a different crewmember as his bunkmate. He avoided officer wardrooms and quarters and rarely associated with officers on liberty. Sinbad was so loved by his fellow Coast Guardsmen that he had his own service number, “069-069,” and his own service and health records. A 1940 Christmas dinner program in the collection lists the names of Campbell’s crew—including Sinbad.

Sinbad was fiercely loyal to Campbell and its crew. Once, in Iceland, he overstayed his liberty and Campbell left without him. He discovered this when Campbell was about 400 yards out and barked ferociously. The crew spotted him and alerted Hirshfield, who said, “What can I do? I can’t write in my log ‘Left dock at 4 pm. Returned at 4:04 to pick up dog.’ It just isn’t done.’” When Campbell did not stop, Sinbad jumped into the icy waters. Hirshfield had no choice but to turn the cutter around.

Liberty Adventures

Like most sailors in the Coast Guard, Sinbad had his share of adventures while in port. Typical liberty for him was going into a bar, finding an empty stool, jumping on it, and barking once for a beer. When he was satisfied, he would leave in search of another bar and more beer. Campbell’s crew always covered his tab. Once, he left Campbell on his own and disappeared into the night. The next day, shore patrol  officers found him staggering down a street, obliviously drunk. Sinbad often went missing while ashore—for two weeks in Boston once. While Campbell was in Italy, Sinbad was court-martials for the Boston incident. Showing no remorse, he was restricted to the cutter whenever in foreign ports. The crew even had their own

officers found him staggering down a street, obliviously drunk. Sinbad often went missing while ashore—for two weeks in Boston once. While Campbell was in Italy, Sinbad was court-martials for the Boston incident. Showing no remorse, he was restricted to the cutter whenever in foreign ports. The crew even had their own S.O.S. call when Sinbad disappeared—“Seen Our Sinbad.”

S.O.S. call when Sinbad disappeared—“Seen Our Sinbad.”

Sinbad’s port adventures were not always liquor-laden. In 1940, Campbell was ordered to serve in Greenland’s waters. Sinbad enjoyed liberty ashore, but had a penchant for chasing sheep, much to the chagrin of the native people. Sinbad was never allowed to set foot in Greenland again. In Belfast, Ireland, local papers published Sinbad’s arrival ahead of time, and he was allowed to attend movies and ride city buses while on liberty. In Japan, he turned his nose up at other dogs, but basked in the company of geishas. In Africa, he was guest at a sultan’s lavish residence. Seamen in Cuba tried to kidnap him, but he fought them off and managed to get away. The French tried to buy him in Oran and, during a port call in Sicily, British seamen offered $1,500 for him.

Sinbad preferred the company of men, though he was always icily polite to women. He never forgot the faces of any of his fellow Coast Guardsmen or the configuration of Campbell. In Sicily, Sinbad missed the boat. He was later picked up by shore patrol officers, who put him on a destroyer bound for the United States. When it reached port, Sinbad barked incessantly. He had recognized Campbell and was soon re-united with his cutter.

Wartime Duty

Wartime Duty

During World War II, Campbell was on convoy duty in the North Atlantic. On Feb. 22, 1943, the cutter endured a 12-hour attack with six Nazi submarines. Campbell rammed one of the submarines, nearly sinking it on the spot. Dog First Class Sinbad snoozed through the entire attack. Campbell sustained severe damage in its starboard side and the engine room was flooded, leaving no electrical power or propulsion. It drifted with no power for five days, until it was rescued by a sm all tug and towed some 800 miles without escort to Newfoundland. The morning after the attack, a destroyer arrived to pick up Campbell’s crew. Naturally, Sinbad refused to leave the cutter. Following this battle, Sinbad was promoted to Chief Dog, but missed his promotion ceremony, and was quickly demoted back to Dog First Class at muster the next day. For his war service, Sinbad was awarded five war ribbons and four battle stars, all of which he proudly wore on his collar. Campbell crewman Seaman Nick Stepich, would say about this battle, “The main thoughts were that you were pretty much closer to God than at any time in your life - God and Sinbad.”

all tug and towed some 800 miles without escort to Newfoundland. The morning after the attack, a destroyer arrived to pick up Campbell’s crew. Naturally, Sinbad refused to leave the cutter. Following this battle, Sinbad was promoted to Chief Dog, but missed his promotion ceremony, and was quickly demoted back to Dog First Class at muster the next day. For his war service, Sinbad was awarded five war ribbons and four battle stars, all of which he proudly wore on his collar. Campbell crewman Seaman Nick Stepich, would say about this battle, “The main thoughts were that you were pretty much closer to God than at any time in your life - God and Sinbad.”

Postwar

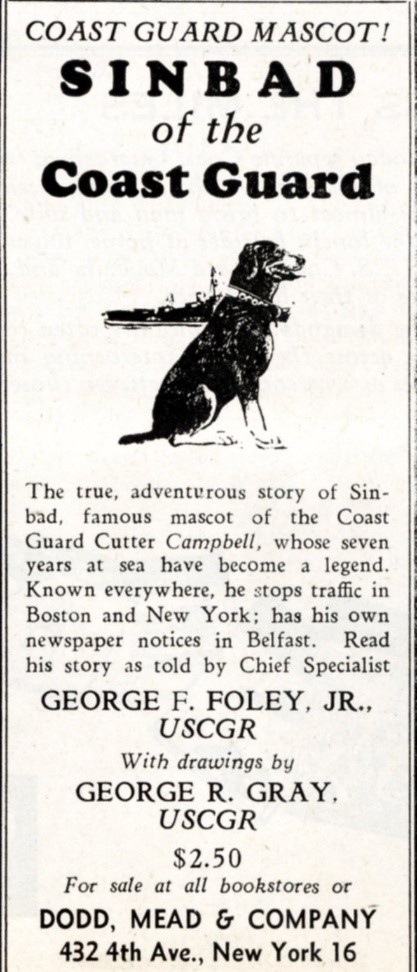

Sinbad’s fame skyrocketed after World War II ended. He had served nine years in the service at this point. The chief of the Coast Guard Press Division in New York, Specialist George Foley wrote the Chief Dog’s biography, “Sinbad of the Coast Guard.”

On Jan. 5, 1946, Sinbad embarked on a national tour of the United States. Photographer’s Mate Leonard Webb photographed Sinbad in ports all over the world and accompanied him on this tour. Starting in New York with a ticker tape parade, the president of the New York City Council welcomed Sinbad, held press conferences, and “pawtographed” copies of his book. A short newsreel, “Dog of the Seven Seas”, was produced the same year by Universal Pictures. Sinbad made personal appearances in theaters and parades in New Jersey, and  helped administer the oath of office for new recruits in Saint Louis, Missouri.

helped administer the oath of office for new recruits in Saint Louis, Missouri.

As Sinbad’s popularity grew, so did his admirers, most of whom were women. In the collection, there is a letter from June Kornet of Ohio. During World War II, she was a clerk in a shipyard office in Toledo, Ohio. Kornet kept a scrapbook about the Coast Guard that had a picture of Sinbad on the cover. In a letter dated March 22, 1947, Sinbad is given glowing praise by Kornet, by then a Western Union operator.

Retirement

Chief Seadog Sinbad retired from the service Sept. 21, 1948, after 11 years at sea. He spent the remainder of his life at the Barnegat (New Jersey) Lighthouse. In a  1950 letter, Barnegat’s officer-in-charge, Thomas Lynch, wrote how reveille meant nothing to Sinbad. Some mornings the Chief Dog would sleep in and other mornings he lay out on the station lawn or visit the city’s dog population. Barnegat Lighthouse is located on a 12-mile-long island, so Sinbad never ventured too far. Everyone in Barnegat knew him, since he still made his beer every now and then. The only time he showed his advancing age was when he barked for assistance up or down a ladder.

1950 letter, Barnegat’s officer-in-charge, Thomas Lynch, wrote how reveille meant nothing to Sinbad. Some mornings the Chief Dog would sleep in and other mornings he lay out on the station lawn or visit the city’s dog population. Barnegat Lighthouse is located on a 12-mile-long island, so Sinbad never ventured too far. Everyone in Barnegat knew him, since he still made his beer every now and then. The only time he showed his advancing age was when he barked for assistance up or down a ladder.

As Sinbad aged in retirement, plans were made for his funeral. A Jan. 27, 1950, letter in the collection, from Chief Journalist Alex Haley, outlined these plans, which, sadly, never occurred. Haley later retired to become the acclaimed writer of Roots and Malcolm X.

Death

Sinbad died peacefully on Dec. 30, 1951, at Station Barnegat at the age of 13, the equivalent of 77 human years. He was buried in an unmarked grave under the flag tower on the grounds of Barnegat Lighthouse. A headstone was added in 1989.

Sinbad was a devoted Coast Guardsman and loyal shipmate during World War II to the point that he provided some comic relief from the monotony of wartime duty. In presenting the Pacific Theater Campaign Ribbon to Sinbad in June 1945, Lt. Cmdr. Richard Johnson, commanding officer of Campbell, stated, “We are assembled to honor what the world describes as a dog. But we, his companions, know he is far more than that. He is a valiant shipmate, a builder of morale, a sympathetic friend, and a symbol of loyalty and unselfish affection.”

Campbell’s last live mascot, a fourth-generation canine named Sinbad, was aboard in 1964. After 46 years of faithful service, Campbell was sunk Nov. 29, 1984, as a target by the United States Navy. However, Sinbad’s legacy lives on today, as the present-day Campbell (WMEC 909) has a statue of Sinbad encased in a glass display on board.